EXHIBITION ESSAY

Joe Zucker: Armada

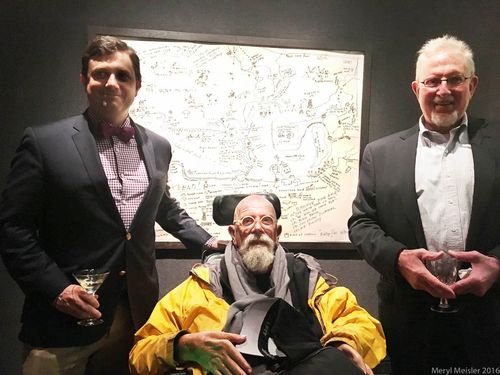

by James Panero

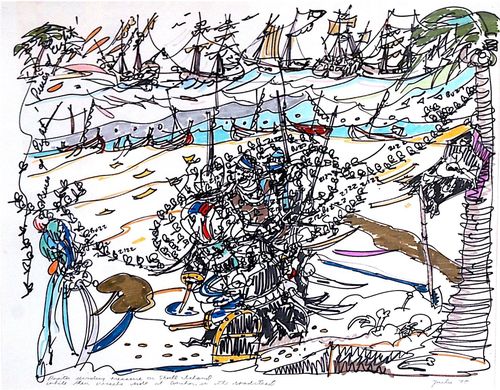

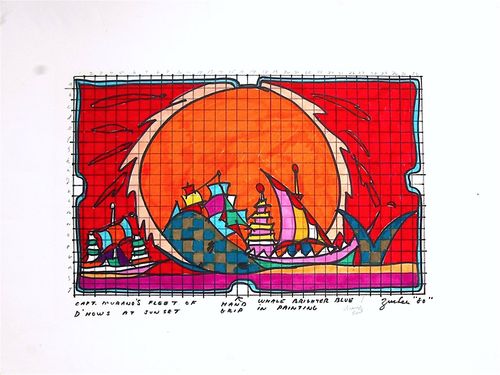

This essay has been occasioned by “Joe Zucker: Armada,” a forty-year survey of Zucker’s works on paper and the first to focus on his images of the sea. Organized by James Panero, “Joe Zucker: Armada” is on public view at The National Arts Club from May 2 through May 28, 2016. (Image: JOE ZUCKER, Capt. Murano’s Fleet of D’How at Sunset, 1980, Felt tip marker on paper, 18 x 24 inches)

Joe Zucker was born in 1941 to a Jewish family on Chicago’s South Side, at a time when the Irish and Italian gangs of the area sparred over territories embroiled in the tensions surrounding black migration and white flight. He got out through varsity basketball and found a moment of jock glory on the squad at Miami University in Ohio. Yet Zucker also happened to be blessed with one of the more interesting minds in American art. This complicated his athletic career and his artistic one as well. Zucker has long been out of step with the dullness that has come to dominate contemporary artistic production.

In 1961, Zucker gave up playing basketball and returned to Chicago to enroll at the Art Institute, where he had been drawing in his spare time since the age of five. His teachers were thinking Braque and the School of Paris. Zucker was more interested in potboilers and the narrative art of Thomas Hart Benton. He passed through the Institute’s bachelor’s and master’s programs, and followed this up with a teaching stint in Minnesota.

Zucker arrived in New York in 1968, one of modern art’s more fruitful moments, when the avant-garde had just passed through the rabbit hole of minimalism and was beginning to re-embrace the craft and process of painting.

At the time, modernism’s recursive instinct seemed to have reached its end-game. Minimalist art and sculpture had folded form back on itself to an infinite and emptying degree. Like other artists of his generation, Zucker used minimalist logic to structure his artistic practice, but he sought to expand this logic to maximal effect.

“You can be tempted into reducing and reducing to the point of emptiness, simply repeating terms dictated by the perimeter of the paint,” Zucker noted in an interview. “I wanted to breach the perimeter and get into the very substance of the painting. I saw that as a way of evading the self-defeating outcome implicit in the reductive logic of modernism.” By infusing his work with narrative and humor, Zucker charted out a singular artistic path.

From his graduate-school days, the subject of the painter’s materials has been one of Zucker’s recurring interests. It was the substance of oil, after all, that received the lion’s share of attention by the Abstract Expressionists. Taking a cue from the revival in weaving and craft-based art, Zucker turned this relationship around and moved the canvas to the foreground, from surface to subject matter. An early series of Zucker’s work consists of abstract weavings of colored strips, recalling the warp and weft of a painting’s canvas.

In the 1970s, Zucker developed work based on the “history of cotton,” which he first showed at New York’s Bykert Gallery, run by Klaus Kertess and Jeff Byers. These large canvases depicted various sepia-toned scenes of the antebellum South: a paddle boat in Amy Hewes (1976); slaves and an overseer in Brick-Top, The Field Hand, and Lucretia Borgia (1976); bales of cotton stacked and hauled in Reconstruction (1976) and Paying Off Old Debts (1975); and the neoclassical facade of Old Cabell Hall in University of Virginia Law School (1976). Yet the layers of representation in Zucker’s cotton constructions complicate a single historical reading.

Like the history of cotton, Zucker has long woven stories of the sea into his diverse body of work. The sea, after all, carried the cotton, the textiles, and the human cargo that created the raw materials of art. As in all of American history, American art history passes directly through the Middle Passage.

In his 1950 book The Enchafèd Flood, W. H. Auden observes how the sea represents a “state of barbaric vagueness and disorder out of which civilization has emerged and into which, unless saved by the effort of gods and men, it is always liable to relapse.”

Pirates, whalers, and slave traders have recurred in Zucker’s undulating imagery, which has engaged with the sea’s creative energy and destructive menace. In his expansive oeuvre, the sea is both the endless horizon and the picture plane of unfathomable depth. For unstable works on paper, water also both creates the medium and can easily destroy it. By building his work through a self-invented process where craft, image, and logic come together in one worked-out puzzle, Zucker’s art becomes both medium and content, work depicting its own history of production as much as the American past. Zucker’s history of modernism is Roger Fry by way of the Jolly Roger—a picture plane shot through with cannon balls.

An experienced fisherman, Zucker is finally an artist who appreciates the sea first-hand. As we onced fished together for striped bass on his small boat “The Rodfather” along the rips off Montauk Point, Long Island, Zucker suggested that the fish beneath our boat lived in a state of chaos—a dog-eat-dog, or, rather, a fish-eat-fish existence of swirling chaos—that would be unimaginable to our terrestrial sensibilities. That dizzying sensation of looking down into the water from our storm-tossed boat calls to mind the feeling I get from Zucker’s own body of work, and one that I hope is reflected in the selection for this exhibition.

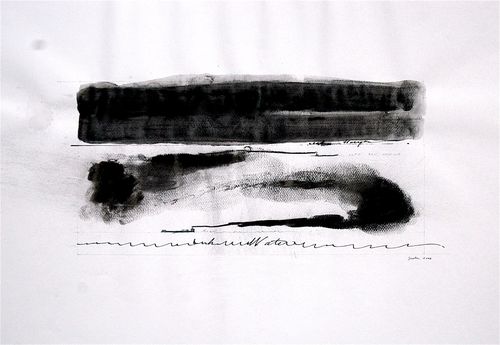

JOE ZUCKER, Dusk, 1998, watercolor on paper, 15 x 24 inches

JOE ZUCKER, Pirate dividing treasure on Skull Island while their vessels ride at anchor in the roadstead, 1978, felt tip marker on paper, 19 x 24 inches

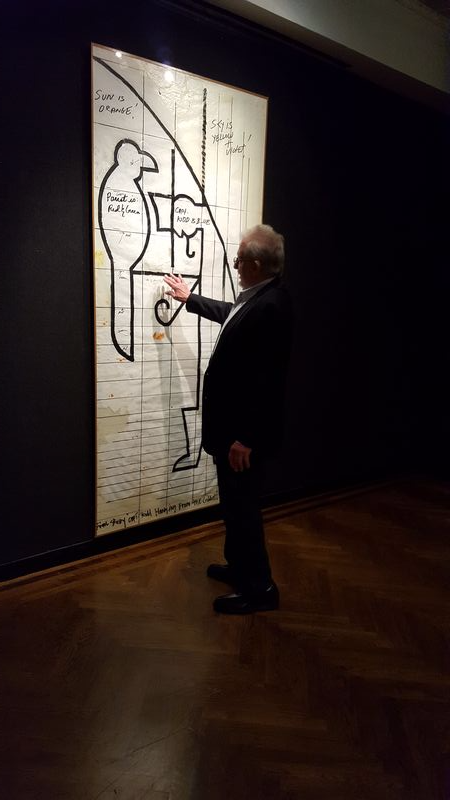

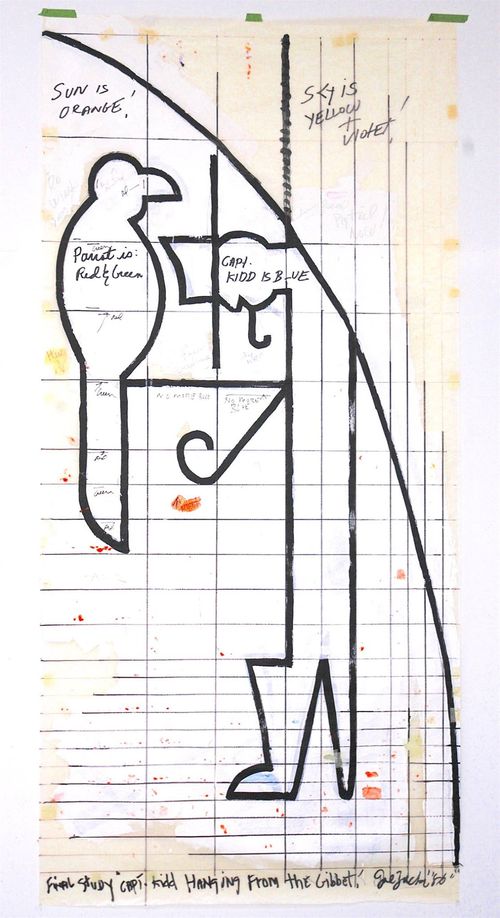

JOE ZUCKER, Final Study Captain Kidd Hanging from the Gibbet, 1986, acrylic on glassine, 101 x 47 inches