THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

August 7, 2017

Discovering Modernism’s Neglected Spur

A review of "Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris, 1892-1897" at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, through October 4, 2017.

Alfred H. Barr Jr., the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, once wrote that “those who love art or spiritual freedom cannot remain neutral… when one kind of art or another is dogmatically asserted to be the only funicular up Parnassus.”

There are, of course, many twists and turns in the history of art, yet the line that runs up Modernist Mountain has often been mapped as a single track: Impressionism, to post-Impressionism, to Cubism, on through the many pictorial innovations of the last century. In this analogy Symbolism, an idealist route of the 1890s, may be modernism’s neglected spur—and an impresario named Joséphin Péladan (1858-1918) its most colorful conductor.

“Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris, 1892-1897,” an intoxicating exhibition now at New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, re-creates the short-lived exhibition series that Péladan mounted in Paris at the height of the Symbolist moment. Organized by Guggenheim senior curator Vivien Greene, the show includes 40 works that once appeared in Péladan’s invitational exhibitions. The artists assembled, like the history of the Salons themselves, will be new to almost everyone, but these Salons were once a sensation, encapsulating the anxious mood of the fin-de-siècle and influencing the art of the 20th century.

‘The Dawn of Labor (L’aurore du travail)’ (c. 1891), by Charles Maurin PHOTO: YVES BRESSON, MUSŽE DÕART MODERNE ET CONTEMPORAIN, FRANCE

Infused with spiritualist mysticism, versed in the poetry of Charles Baudelaire, and set to the soundtrack of Richard Wagner, Symbolism championed art, literature and music of many styles—all art with a capital A, with fidelity to nature subordinated to the expression of the artist’s mood. In “Mystical Symbolism,” the outward appearances can seem anything but modern. Artists such as Pierre Amédée Marcel-Béronneau and Ferdinand Hodler looked past what they considered the mundane observations of the Impressionists to draw on the Old Master styles of Gustave Moreau and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes.

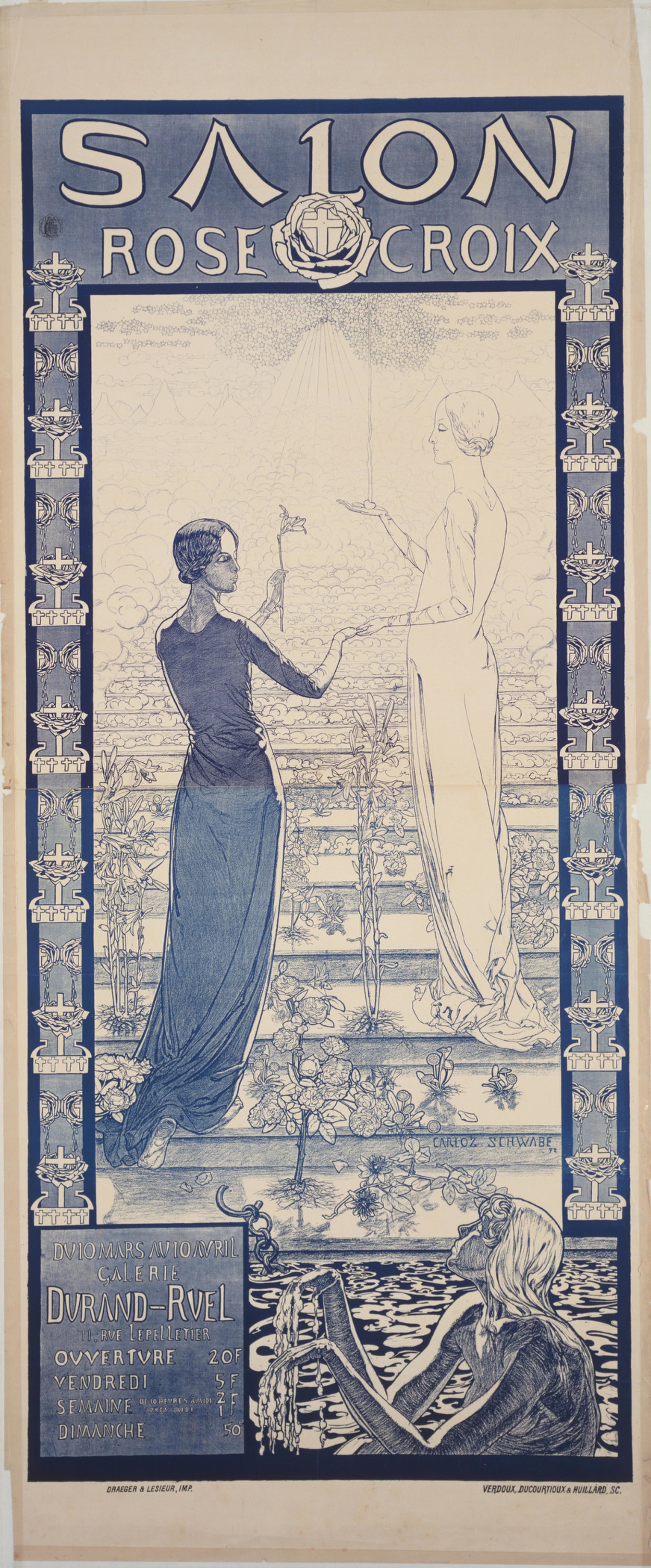

Carlos Schwabe’s poster for the first Salon de la Rose+Croix (1892) PHOTO: THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART/LICENSED BY SCALA/ART RESOURCE, NEW YORK

Péladan embodied this same rear-guard sensibility. He styled himself an Assyrian “Sar,” or king, and named his group Rose+Croix after the esoteric and arguably fictitious Rosicrucian Order of 17th-century origin. Through his Salons he sought work that illustrated dreams, allegory and myth “to restore in all its splendor the cult of the Ideal based on Tradition with Beauty as its means.” The story of Orpheus, that original tragic artist, is a recurring theme here, and maidens abound in various stages of déshabillé. The exhibition is most revelatory for the many artists, from Charles Maurin to Fernand Khnopff, Jan Toorop to Alphonse Osbert, it brings to light. The dream-like lithograph by Carlos Schwabe, commissioned to promote the first Salon, is a highlight of fin-de-siécle printmaking.

The Guggenheim exhibition hinges on the personality of Péladan, and “Mystical Symbolism” includes portraits of the artistic leader. This author, critic and Catholic occultist employed his imperious bearing and forked beard to maximum effect: Especially striking is Jean Delville’s messianic figure in choir dress and Alexandre Séon’s priestly golden profile.

Pierre Amédée Marcel-Béronneau’s ‘Orpheus in Hades (Orphée)’ (1897) PHOTO: CLAUDE ALMODOVAR/COLLECTION DU MUSEE DES BEAUX-ARTS, MARSEILLE

In her red-velvet-bound catalog, Ms. Greene explains how the Salon de la Rose+Croix “privileged a hermetic and numinous vein of Symbolism, which reigned during the 1890s when Christian and occult practices were often intertwined in a quest for mysticism undertaken by many who yearned for a renewed centrality of faith. The Salon aimed to transcend the mundane and material for a higher spiritual life—the movement’s holy grail.”

Ms. Greene’s focused and illuminating exhibition, which goes on to Venice’s Peggy Guggenheim Collection in the fall, continues the New York museum’s commitment to exploring modernism’s less trodden paths. But equally important, the museum shows respect for the art and ideas on view. With deep red walls and plush blue couches, Ms. Greene and her designers have done much to establish this exhibition as a Rosicrucian-like art-filled precinct. The addition of recorded music in the galleries, normally a distraction in museum settings, here completes the transformation of the space and signals the relevance of music to Symbolist history. Ms. Greene, in fact, selected only music performed during the original Salons—most famously, a work by Erik Satie written for the Rose+Croix.

‘The Death of Orpheus (Orphée mort)’ (1893), by Jean Delville PHOTO: ROYAL MUSEUMS OF FINE ARTS, BELGIUM, BRUSSELS: J. GELEYNS-RO SCAN

And far from a dead end, the art of the Rose+Croix, and Symbolism in general, may lead more directly than one might assume into the art of the 20th century, especially in the development of pure abstraction. “The aesthetic quest of the R+C—to inspire through the new religion of art,” argues Ms. Greene, “was carried on by Vasily Kandinsky, František Kupka, and Piet Mondrian, all of whom were weaned on Symbolism and owed their theories of painting, in varying degrees, to the esoteric beliefs of Theosophy.”

So perhaps it isn’t a coincidence that the exit of “Mystical Symbolism” leads directly onto the Guggenheim’s magical Kandinskys and Mondrians hanging on the rotunda walls.