THE NEW CRITERION, March 2020

On ill-advised renovations to a New York treasure.

The Frick Collection will soon be strictly for the birds—or, more strictly, for a goldfinch. It was a goldfinch, or, strictly speaking, the painting The Goldfinch by Carel Fabritius (1654), that so swelled the crowds of this beloved jewel-box institution in 2013. In that year The Goldfinch made a rare migration from its perch at the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis in The Hague. It flew past the typical nesting grounds of blockbuster traveling exhibitions to alight, of all places, on the walls of the house museum of Henry Clay Frick. Sent along for the flight were a few additional birds from the Mauritshuis, then undergoing renovation, including Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (ca. 1665). In other words, two paintings that were the bases of two separate bestselling books, which were both adapted into Hollywood movies, were making a single stateside stop. The corner of Seventieth Street and Fifth Avenue had never seen so many ruffled feathers. New Yorkers clambered to get a ticket to the show of the season—and maybe even see a painting or two.

“Masterpieces of Dutch Painting from the Mauritshuis” overwhelmed the small institution. Attendance went up by more than a third for the year. Around the brief run of the show, 120,000 more people came to the Frick than ever before. Undoubtedly, these numbers would have been even higher if the collection had more space to handle the crowds. And so, as might be expected in our current arms race over turnstile numbers, no sooner had The Goldfinch flown the coop than did the Frick mount its case for a major expansion. What was clearly not expected, at least by Frick leadership, was just how poorly that case would be received.

While retaining the feel of a Gilded Age home, The Frick Collection, after all, has seen a century of smart revision. The institution has, until now, been the great beneficiary of sensitive and seamless concatenations that have allowed it to evolve over time into one of America’s finest collections of European painting. It has done this all while standing apart from the expansive mandates of mainstream museum culture. I doubt I am alone in making this my primary recommendation to any out-of-towner visiting New York: be sure to see The Frick Collection.

It helps that Henry Clay Frick always intended his home and collection to be given to the public trust. When he set about creating his Fifth Avenue mansion at the turn of the last century, he drew inspiration from London’s Wallace Collection. Richard Wallace, the illegitimate son of the fourth Marquess of Hertford, bequeathed his paintings and home to the British nation. That collection opened in 1897. Frick, the great American industrialist of steel and rail, likewise conceived of a house museum that would keep his singular art collection intact after his death.

Engraved bookplate, commissioned by Helen Clay Frick, showing her father Henry Clay Frick in the Living Hall of his New York residence. With facsimile inscription: “Those who do not read are going back instead of progressing.” Quotation is taken from a letter from Frick to his daughter dated 7 July 1903. Courtesy of The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives.

In 1914 the firm of Carrère & Hastings, fresh off the job of designing the main branch of The New York Public Library, turned its attention to the restrained Beaux-Arts mansion we still see a mile and half up Fifth Avenue. But beyond Frick’s house and gardens facing the avenue—a country home in the city—Thomas Hastings also gave sensitive thought to the gallery wing running along Seventy-first Street. Here Ionic pilasters and playful entablatures break up the monotony of a windowless wall while reflecting the order of the domestic façade and spaces within. The stage was set for a house that would become a home for great art.

After Henry’s death in 1919, his widow, Adelaide, and his daughter, Helen, set about advancing these philanthropic interests as Adelaide lived out her years in the family manse. Following Adelaide’s death in 1931, in accordance with Henry’s bequest, the collection became an institution in the public trust. Under its first organizing director, Frederick Mortimer Clapp, the family and trustees of The Frick Collection commissioned the architect John Russell Pope to bring Henry Frick’s wishes to completion.

View of the original driveway of the Frick residence at One East 70th Street, leading into the porte-cochère toward Seventy-first Street. The entrance underwent significant renovations in 1935. Photo: Ira W. Martin, 1927. Courtesy of The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives.

Pope’s 1935 interventions into the fabric of the Frick home remain a master class in adaptive design. He converted the mansion’s porte-cochère, which ran behind the home from Seventieth to Seventy-first Streets, into a new entrance and the skylit Garden Court. These spaces became the public center of the new institution. They led seamlessly onto the mansion’s first floor, revealing a supreme collection of paintings—including masterpieces by Bellini, Titian, Bronzino, El Greco, Velázquez, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Boucher, Fragonard, Goya, Turner, and Ingres—without disrupting their domestic setting. In what is called the Living Hall, dueling portraits by Hans Holbein, one of Thomas More and the other of Thomas Cromwell, continue to glower at one another across a mantelpiece just as they did in Frick’s day in the sumptuous oak-paneled room.

John Russel Pope’s Garden Court, viewed from just beneath what used to be the driveway’s porte-cochère. Courtesy of The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives.

In addition to opening up Hastings’s living spaces, Pope created a new set of radiating rooms of exquisite variety: the Oval Gallery and the square East Gallery, both extending the axis of Thomas Hastings’s long West Gallery; and a circular Music Room, a salon for concerts, lectures, and exhibitions. Expanding into an open lot to the east, Pope also backed these additions with a new six-story Art Reference Library, a major initiative of Helen Clay Frick underway since 1920, replacing a smaller Hastings-designed structure. Pope’s light-filled limestone Library, which remains an essential art-historical resource, rises above the Frick mansion on Seventy-first Street but is set back just enough as to be concealed when walking by the house on Fifth Avenue.

A high classicist of American architecture, Pope molded sumptuous Roman spaces onto the Beaux-Arts academe of Hastings, perfectly eliding the points where Hastings ends and Pope begins. Pope even moved and reworked existing details, giving his additions a truly seamless appearance. He reused Sherry Fry’s pediment above the original porte-cochère, now an internal hallway, for his new Seventieth Street entrance. On Seventy-first Street, he pushed another pediment east as he extended Hastings’s gallery façade. Could it be the Ionic columns of Pope’s peristyle Garden Court were once the outdoor ornaments of the Frick driveway? Against the false contemporary belief that new additions must stand apart from historical structures, Pope turned a building of many parts into a unified whole.

It was this sense for contextual expansion that informed a new set of designers, more than a generation later, to fill in an open lot to the east of the Frick’s public entrance. By 1977, in proper architectural circles, seamlessness was considered shamelessly unseemly. Yet the architect John Barrington Bayley, working with the English garden designer Russell Page, risked professional disapprobation by extending the vocabulary of Hastings and Pope into a new ticketing hall and viewing garden. The new exterior addition was a bit clunky, the interior a bit chunky, but the gesture gave license to a new generation of revivalist architects and designers as Page’s idiosyncratic garden became, to many, a living sculpture.

In 2014, drawing on the firm’s well-regarded 2011 enclosure of the small Portico Gallery, Davis Brody Bond proposed a significant enlargement to the Frick physical plant, mainly by filling in the Page garden lot and extending the envelope of the Art Reference Library to Seventieth Street. The Frick’s arguments for expansion were not without some merit. The Collection lacks a loading area, meaning that art movers must park right out front. A primary space for special exhibitions is narrow and subterranean, accessed mainly through a small door and spiral staircase. Henry Frick’s historic upstairs rooms are currently off-view, filled instead with staff offices. The coat check is little more than a closet, while the one beverage on tap is water. The Collection, at least to its critics, simply does not seem like a modern museum should.

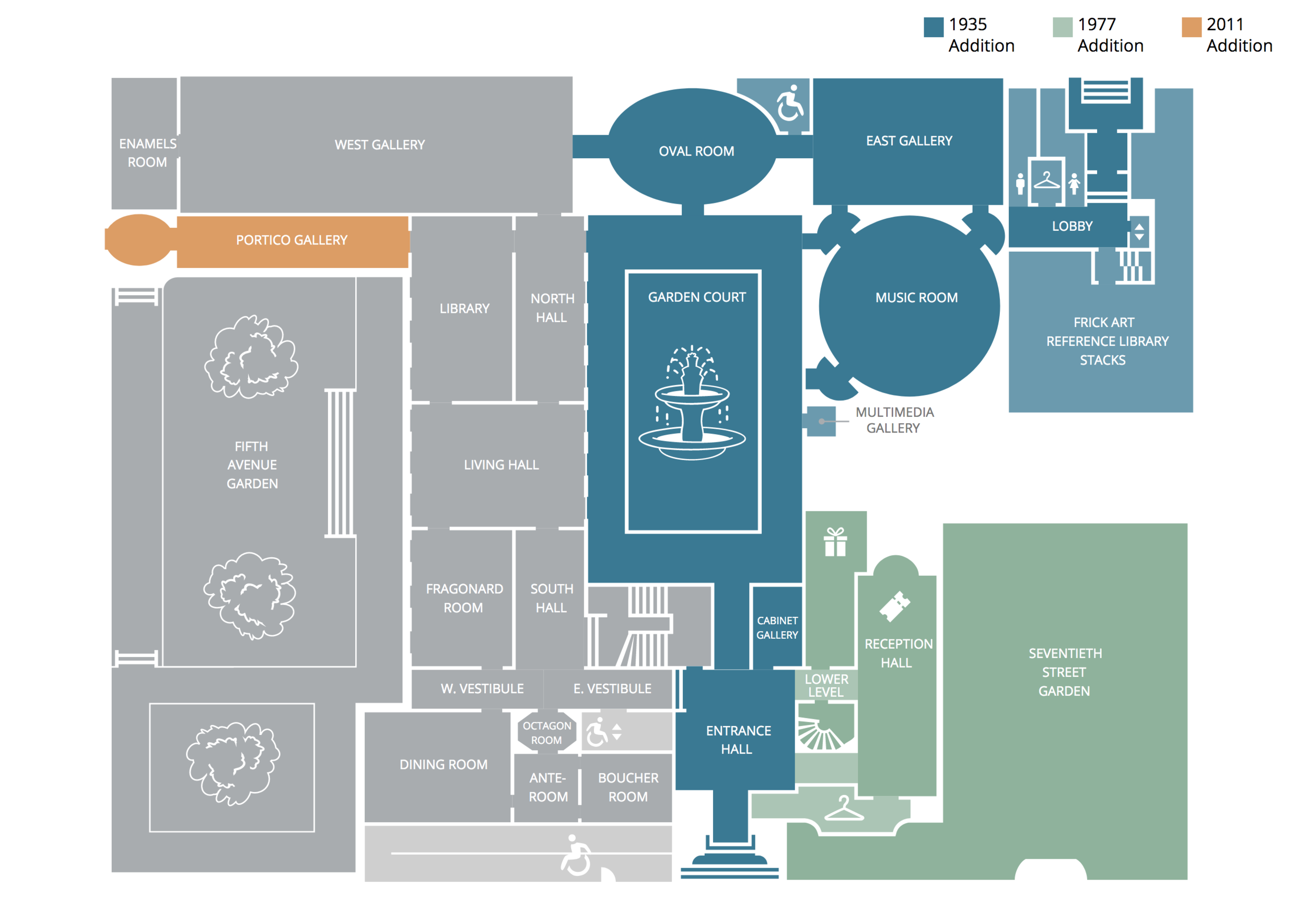

A map of the Frick’s current floorplan. Courtesy The Frick Collection.

Bond’s proposal also made some architectural sense. Pope clearly meant for his Library to be extended into what became Page’s garden space once those building lots became available. The Library building now terminates to the south mid-block and mid-slice. Bond proposed finishing that façade in quasi-period detail in matching Indiana limestone, adjoining the building to Pope’s Seventieth Street entrance and continuing the cornice lines of Hastings’s original mansion, maintaining if not even enhancing the seamlessness of the Frick whole.

The opposition to this plan was swift and organized. In the wake of a successful fight to save Carrère & Hastings’s New York Public Library main branch from a needless trimming, a coalition called United to Save the Frick joined forces with the American Society of Landscape Architects and the Municipal Art Society to end the plan. At sixty thousand square feet, the size of the expansion seemed excessive. The modernists also objected to its contextual elisions—its very seamlessness. But the battle ultimately came down to the Page garden. This mid-block space is an anomaly, clearly—if anything, an uncontextual break in the Manhattan street wall. Such a tiny garden does not warrant preservation for environmental reasons alone. Plenty of “green space” remains available right across Fifth Avenue—and even along the Frick’s western side. Central Park is famously open to public use, while I have never seen anyone in Page’s burbling quadrangle. Yet Page had his supporters. One of them even dug up a statement from the Frick, issued in the early 1970s, saying this mid-block garden would become permanent. Now possibly up against legal as well as cultural opposition, the Frick went back to the drawing boards.

A rendering of the proposed renovations by Selldorf Architects, viewed from Seventieth Street

On the face of it, the new expansion plan issued last year by Selldorf Architects, with twenty-seven thousand square feet of new construction, looks to be a restrained compromise. In reality, with an additional sixty thousand square feet of “repurposed space,” it will be even more invasive than the Bond design. Rather than the Rome of the Caesars, Selldorf’s slick classicism looks to the Rome of the Mussolinis. The Page garden will be maintained, or at least replanted after it has been ripped out, but at the expense of destroying the essential harmony of Pope’s forms. The grand limestone windows illuminating the Library’s Reading Room will be partially obscured by a new modernist cube—a sorry loss, as I write these words from the Reading Room’s sublime space. This square addition will be jackhammered into the round hole of Pope’s intimate Music Room, which will be senselessly destroyed. The southern façade of the Library will not be completed, as in Bond’s plan, but now refaced in buff brutalism. Bayley’s contextualized entry pavilion will also be gutted and replaced by a slick reno of glass, metal, and stone. Despite a valiant effort by the preservationists to draw attention to these many infelicities, the new plan steamrolled through city approval. The demolition may now begin in a matter of months as the Frick closes for two to four years for its $160 million facelift.

Plans for the Music Room’s demolition and the proposed replacement, a “special exhibitions” space.

The Frick is serious. It is unique. In its exhibitions and scholarship, its leadership—directed since 2011 by Ian Wardropper—has exemplified these qualities. I do not doubt their belief that these expansion efforts come from a place of serious need. It is this same seriousness that has driven their many critics. The Frick is great precisely because it is a unique collection of art and architecture in a world of increasingly homogenized big-box museums. Its limitations have not been to its detriment but, instead, have ultimately been its saving grace. The small size of its rotating galleries has compelled it to pursue an exceptional run of focused exhibitions. Its domestic scale has kept its experience personal and thrilling. Its lack of amenities has also meant that everyone is there for the same reason: to have an absorptive engagement with the masterpieces of art.

The critics of expansion were never trying to save one element of the Collection while sacrificing another. They were simply sending the message that, in our era of change, sometimes the most urgent argument is to stay the same. I wish this had been heard. The Frick Collection is perfect the way it is—or rather, it was.