THE NEW CRITERION, February 2025

Sabin Howard has been at the center of a battle over sculpture for over three decades. I first wrote about him in this space nearly twenty years ago, when I paid a visit to his studio in the South Bronx and found him surrounded by a pantheon in plaster and bronze (see “Gallery chronicle,” May 2007). At the time, Howard was completing a statue of Apollo. As with all of his work, this multiyear labor, built up through tens of thousands of hand-applied dots of plasteline, was destined to be cast in an alloy, one might say, of his own autobiography. Howard sculpts in epic and myth, including his war against our cultural status quo. He has long approached the plastic arts as if he were a Prometheus, a fallen god out to redeliver that creative fire from Mount Olympus.

I doubt I was the only observer who felt a mixture of elation and apprehension when, in 2016, the U.S. World War One Centennial Commission selected Howard out of some 350 submissions to design the centerpiece for its new war memorial on the Washington Mall. Here was a creative battle to end all art wars. I feared one unelected agency after another would wear down this aesthetic belligerent to a stalemate, if not gassing him into unconditional surrender.

It did not help matters that the designated site of Pershing Park, just around the corner from the White House, already contained a design from 1981 that had been the result of an earlier competition involving no less than Robert Venturi, Richard Serra, and M. Paul Friedberg—establishment grandees all. True, their site had been in decline for decades. First it was shoehorned into a sunken ice rink, then a swamp designed by the firm of Oehme, van Sweden, and finally a brownfield site of broken water features, abandoned postmodern pavilions, and a derelict garage for the Zamboni. Despite the sorry state, preservationists were quick to panic in this needle park as they dug up Kodachromes from opening day, 1981. Any commission would need to accommodate Pershing Park’s bones—including its existing monumental plaza dedicated to General John J. Pershing, which had been designed by Wallace K. Harrison with a statue by Robert White from 1983—even as it looked to create something revivified and new.

The location of the memorial site was just one of Howard’s many troubles. Our nation’s art-and-architecture insiders were sure to see the selection of Howard and his competition partner, Joseph Weishaar—a twenty-five-year-old graduate of the University of Arkansas, an architect who did not yet have his license at the time of the announcement—as interlopers in what was supposed to be an exclusive lawn party for pedigreed insiders. After all, the last starchitect to dip his beak in the National Mall was none other than Frank Gehry. In 2020, he left it with an anti-monument made of chicken wire, purportedly dedicated to Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Of course, the war over the National Mall goes back much further. In 1982, Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial, submitted when she was an undergraduate at Yale (whew!), was a minimalist broadside against the capital’s classical aspirations. The assault was only somewhat countered two years later by the addition to the site of Three Soldiers, Frederick Hart’s realistic bronze sculpture of multiracial brothers-in-arms.

Sure enough, as I tuned in to view the endless agency meetings in the years following the commission announcement, it seemed as though Howard and Weishaar’s concept, called “The Weight of Sacrifice,” would be bled through a thousand bureaucrats. What initially called for three walls of engravings, all designed to surround a freestanding battle sculpture and an elevated lawn, was eventually reduced through eighteen different iterations to a single wall of sculptural relief less than sixty feet in length. Weishaar’s elevated lawn, meanwhile, returned back to Friedberg’s sunken plaza, now merely modified and tidied up, with Howard’s sculptural frieze essentially replacing the old Zamboni dock. (gwwo Architects, meanwhile, stepped in as managing architects, with David Rubin Land Collective serving as the landscape designer.)

The pressures might have been enough to shell-shock any creative soul. For Howard, it appears to have fired up some essential distillation, encouraged by his commissioners, including Edwin Fountain, as well as by Justin Shubow of the National Civic Art Society. Relief sculpture going back to antiquity has a special ability to convey the cycles of war. Unlike freestanding statuary, its program can be episodic. Rather than a single moment, relief can contain many moments across a single frame progressing from left to right, as for example up the spiral of Trajan’s Column in Rome.

Howard appears to have drawn from numerous sources as he recast his sculpture into what he titled A Soldier’s Journey—a long frame of a single figure in multiple scenes as he turns from his daughter and wife, marches off to war, faces the ferocity and terrors of the trenches, and returns home to his family. Howard’s wife, the novelist Traci L. Slatton, as project manager recorded the evolution online in preparation for a documentary about the commission called Heroic, to be released this summer. She also served as a model for a nurse in the composition; their teenage daughter provided the model for the girl at the start and end of the frieze.

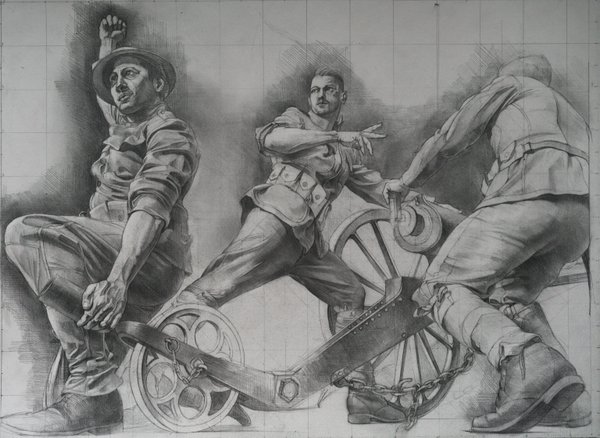

For inspiration Howard looked to Ghiberti’s baptistry doors in Florence and John Singer Sargent’s Gassed, that epic processional painting of blinded soldiers from 1919 based on Sargent’s own frontline observations, now in London’s Imperial War Museum. The minimalism of Lin and the realism of Hart both seemed to become reflected in the synthesis of the evolving relief. So too the turmoil of Henry Merwin Shrady’s sculptural battle groups for his tripartite Ulysses S. Grant Memorial, which leads up to the United States Capitol from the west. That work took Shrady twenty years to complete and accelerated his untimely death in 1922 at just age fifty, a fact that did not bode well for Howard. The Grant Memorial was only completed by Shrady’s studio assistants Edmond Amateis and Sherry Fry. (Shrady’s pendant equestrian statue in Charlottesville of Robert E. Lee, completed by Leo Lentelli in 1924 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1997, was removed and melted down in 2023 as a consequence of the moral panics of 2017. This is just one of the many recent crimes against our sculptural patrimony that has yet to be redressed.)

Howard’s most significant invention in A Soldier’s Journey was surely mothered by the necessities of his impending deadline and what he could fully do with the sculptural space that remained for him. For an artist who could spend years building up a single statue, a multipart relief of more than three dozen figures, all over life size, could quickly add up to a terminal Shrady sum. A manual artist, Howard turned to digital solutions. At first he took some twelve thousand pictures of his models, posed in authentic period uniforms, with his cell phone. The many models—a mix of actors and military veterans along with his family members—recited period poetry during the long posing sessions. “Dulce et Decorum Est,” written by Wilfred Owen in 1917 and published posthumously in 1920, proved to be particularly relevant to the emerging sculptural story:

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

To advance his production schedule further, Howard relocated for nine months to New Zealand, where he worked with Wētā Workshop, the concept-design company behind the Lord of the Rings franchise. Through Wētā’s digital modeling software, he developed and tweaked his sculptural maquettes to secure commission approval. With his models and their wardrobes in tow, Howard then traveled to the Cotswolds in England to work with Steve Russell Studios and the Pangolin Editions foundry. Here he positioned his models one by one in a 360-degree photogrammetry rig—a cage of 156 inward facing cameras feeding three-dimensional scanners—for a final round of imaging. After digital editing, Pangolin milled foam mannequins of these figural forms, which were left coated with a thin layer of clay.

Beyond merely accelerating his development time, this digital process significantly altered Howard’s final results. His use of digital modeling not only helped him to arrange his figures but also allowed him to build his relief more fully in the round, with increasingly true-to-life complexity. With the foam figures back in his studio, now a garage in Englewood, New Jersey, he sliced and diced slivers off of them while slapping on additional layers of plasteline. The action added an expressionistic finish and an urgent manual dash to the underlying digital printouts. The entire assembly was then cast by Pangolin in large bronze sections. In a final step, Howard patinated his bronze in dark gray with a brush and blowtorch.

Technological advancements have always upended creative practice in both destructive and generative ways that can be long debated. A century ago, the sculptor Paul Manship lamented the imposition of the Janvier Reducing Machine even as the mechanical lathe allowed sculptors to rescale their reliefs as never before (see my “Tokens of culture” in The New Criterion of December 2024).

A Soldier’s Journey, by Sabin Howard, The National WWI Memorial, Washington, D.C. Photo: James Panero

For an artist long dedicated to the importance of manual craft, Howard’s digital intervention has created a hybrid sculpture. A Soldier’s Journey is not classical in its own right. It is rather a modern work that speaks to the classical tradition, quite literally, through a contemporary lens. Viewing the completed assembly soon after its unveiling last September—most revealingly in the stark spotlights that illuminate the monumental site at night and shimmer in its reflecting pools—I sensed I was experiencing not traditional sculpture at all but rather actors frozen on a stage. The uncanny-valley hyperrealism of Howard’s digital scans has left us with a cinematic diorama caked in plasteline mud. In memorializing a war that defied all convention and accelerated our modern era, this end result may ultimately be more successful than any purely classical relief. Staring at his figures, which seem to stare right back as they march and spin and cry through the muck, I regarded the work as an unalloyed triumph.

It should come as little surprise that movie-making, an art form coming into its own at the time of the First World War, should have proven so successful at depicting the flashing terrors of that modern slaughter—and in turn influencing more traditional creative forms. King Vidor’s 1925 film The Big Parade remains one of the finest reflections of that conflict and deeply informed the cinematic painting style of Andrew Wyeth. The films All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), Paths of Glory (1957), and, more recently, 1917 (2019) have all arguably done more to keep World War I in the popular consciousness than any other form of art.

Howard has taken up this cinematic idiom to give us a sculptural statement on the First World War that manages to make its century-old realities newly real. At the same time, his composition speaks to the history of relief in bold new ways. I was particularly struck by his use of traditional relief framing at the start of the composition that then appears to crumble away in the mire of battle. Further along, an American flag rises above the relief’s upper frame to signal the new standard on the horizon and the turning point in the war. Throughout the deep relief, the helmets and weapons and gas masks that are scattered about appear as though they could almost be kicked off the stone plinth and into the cascading fountain and reflecting pool beneath them.

At the unveiling ceremony, Howard aptly reflected on the message of his figures and what he hoped to achieve with a monument that gives new life to an old conflict:

There are no victims here. They are all heroes. They are all moving forward, calling upon their better selves, and giving unstintingly to their country, to protect what we so often take for granted, our freedom to choose what we will do with the gift of life.