THE NEW CRITERION, January 2017

On art in the age of Trump.

America’s cultural fault lines should have become apparent even before the seismic shock of the latest presidential election. Now we might ask what role art could play in bridging that divide. Our stratification has become increasingly unstable. Regardless of one’s political views, the solution should not be greater segregation but new efforts at cultural integration.

The country’s cultural division was the subject, of course, of Charles Murray’s penetrating 2012 book Coming Apart: The State of White America 1960–2010. Here Murray observed how a “high-IQ, highly educated new upper class has formed over the last half century. It has a culture of its own that is largely disconnected from the culture of mainstream America.” To prove the point to his readership, which he assumed would largely be of this new class, Murray posed a series of questions called “How Thick is Your Bubble?” The quiz has now been widely distributed through an online version published by pbs’s NewsHour. It asks questions such as whether you have ever walked a factory floor, known low academic achievers, or regularly eat at chain restaurants—experiences that might show shared experiences with working- and middle-class Americans.The quiz should be compulsory testing for any latter-day Pauline Kael who cannot understand a political outcome so out of step with elite expectation—which was the true shock of this election.

It was Kael’s fate for her life’s work as a film critic to become overshadowed by a single political quip: that she couldn’t understand how Nixon won, because no one she knows voted for him. That aphorism, it should be noted, turns out to be somewhat off from what Kael actually said. At a 1972 talk before the Modern Language Association, Kael remarked that “I live in a rather special world. I only know one person who voted for Nixon. Where they are I don’t know. They’re outside my ken. But sometimes when I’m in a theater I can feel them.” So Kael was acknowledging her own provincialism while also, perhaps, demonstrating relief at the segregation that created it—even as she could occasionally “feel” the presence of a Nixon voter in the demotic assembly hall of the American movie house.

The takeaway of Murray’s study might be that we are all Pauline Kaels now, increasingly divided not by a wall but by the cultural fortifications that surround the city-states from flyover country. I say this as a critic, not unlike Kael, writing from inside the battlements. When I took Murray’s latest quiz, in which lower numbers indicate greater degrees of insularity, I scored a mere eight out of a hundred—a number so impenetrably low that it falls below even the average median of 12.5 for my boyhood neighborhood on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, which Murray reveals to be the “bubbliest zip code” in the United States. And I must say even as I have moved on and up (two zip codes north), most people I know still live in this “rather special world” of separatist identity that run deeper than presidential preference. It is a cultural deficiency I acknowledge, and one that I have tried to confront in this column by looking to the tributaries and backwaters of the artistic mainstream.

After all, such separation does not make good culture. It is certainly not a healthy culture, but rather one made of equal parts disdain and resentment. It is also not a rich culture, with the dynamics of America at full throttle. Just what could be done about these divisions is a question that should now be posed by our cultural institutions, our artists—and by government itself. What follows are a few possible answers.

In the museum world, one of the most successful recent examples of bridging our cultural divide has been the creation of the (appropriately named) Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, which opened in Bentonville, Arkansas in 2011. Tucked deep in Ozark hill country, with a complex designed by Moshe Safdie that spans a bubbling body of water called the Crystal Spring, the museum is a literal bridge of American art in a culturally underserved area of the country. If you haven’t been there, I encourage a visit, with fifty flights a day landing in nearby Fayetteville and a boutique “museum hotel” that connects by sylvan bike paths to the institution, which should increase the comfort level of even the bluest of blue-staters.

The Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Founded by Alice Walton, the heiress of the Wal-Mart fortune, and constructed with funds north of one billion dollars by the Walton Family Foundation, Crystal Bridges bucks all conventional wisdom on who, where, when, why, and what a major museum should be. “Swim upstream,” wrote Sam Walton, Alice’s father, in his 1992 autobiography, published the year he died. “Go the other way. Ignore the conventional wisdom. If everybody else is doing it one way, there’s a good chance you can find your niche by going in exactly the opposite direction.” By choosing to locate a new world-class museum far beyond our wealthy urban centers, Alice Walton has been an iconoclast in culture just as her father was in business, all while giving back to the hometown that still maintains the original “Walton’s 5&10” (which is now also the company’s museum).

Crystal Bridges’s truly counter-cultural formation has also been reflected in its maverick programming—so unlike many other inland museums that operate more like colonial outposts of coastal elitism camouflaged in pandering condescension. Two years ago I visited Crystal Bridges for a survey of contemporary art called “State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now,” an exhibition I covered in these pages in October 2014. In search of artists whose “engagement, virtuosity, and appeal” have gone underappreciated, the museum’s director and curator hit the road on a 100,000-mile coast-to-coast visit of 1,000 artist studios. They logged 218 flights and 2,396 hours in rental cars, recording 1,247 hours of audio conversation and extensive video as they narrowed their selection down to the 102 artists to include in their 19,000-square-foot exhibition. “The vision on which Crystal Bridges was founded, and its mission today, is to share the story and the history of America through its outstanding works of art,” Alice Walton told me at the time. “That’s exactly what ‘State of the Art’ is about—sharing works that are being created in artist studios all across the country, in our own time.” “The mainstream is very narrow,” added Don Bacigalupi, the museum president who spearheaded the initiative with Walton. “Our exhibition is outside the mainstream structure of the art world.” Granted, such a wide net will necessarily bring in a haul of various quality, but at least this diverse selection of contemporary American art, created in just about every corner of the country, was a refreshing departure from our art fairs and biennials. It was also an indication that we all need to hit the road.

A decade ago an artist named Scott LoBaido did just that—he went on the road to paint the American flag across fifty rooftops in fifty states. He crossed back and forth over the country nearly two times. In the process, he went broke. He was attacked by wild animals. He dodged twisters. He took a container ship to Hawaii. He slept outside on a twenty-two-hour ferry ride to Alaska. He relied on strangers for food and shelter. And as curators look to the state of political art post-election, they might consider giving equal time to the conceptual and painted work of this self-styled “creative patriot.”

Scott LoBaido

A self-taught artist living just a ferry ride from the heart of the art world, LoBaido hails from that other New York City—the middle class, flag-waving, Republican-voting borough of Staten Island. I first met LoBaido in September 2004, at a show of his paintings at a gallery in lower Manhattan, off Broadway, timed to the Republican National Convention (“Gallery Chronicle,” October 2004).

A year after I met him, I got word that he was in Mississippi working in the relief effort after Hurricane Katrina. He had driven a truck of supplies down from Staten Island, offering his skills in wood and paint. It was in Mississippi that LoBaido made a connection between Katrina and the other great tragedy of his life: the terror attacks of 9/11. In Mississippi, he saw a spirit of hope, renewal, and patriotism that he believed could unite people from very different worlds. He was then inspired to paint an American flag on one of the Gulfport rooftops. He donated his truck to the relief effort, and on his twenty hour bus-ride home, the idea for “Flags Across America” was born: a visible display from the ground and from the air. He said he wanted to send an artistic message to the troops flying home from war. Back home at bar on Staten Island called The Cargo Café, where he was artist-in-residence, LoBaido loaded up a 1989 Chevrolet Suburban named Betsy, a replacement gift from a friend painted in the colors of the American flag: this was the beginning of “Flags Across America.”

LoBaido’s efforts earned him a profile as “Man of the Week” on abcNews. Yet when I told his story at a conference of the College Art Association and made the case for him as a legitimate political artist, the audience, needless to say, wanted none of it. Most recently, LoBaido has made a name for himself again: this time for painting a red-white-and-blue “T”-shaped billboard in Staten Island. This sign, and his flag murals, have been the repeated targets of vandalism and arson. LoBaido’s dissent from cultural orthodoxy is not mere novelty; it is heretical, which should say much about the diversity promises of the cultural establishment. Until this changes, much of America will never see themselves reflected in those mandarin surveys of contemporary American art such as the Whitney Biennial, despite their overtures to inclusion.

Even beyond the National Endowments, there are now dozens of presidential appointments and thousands of Federal employees dedicated to American arts and culture. The new administration could do worse than seek out the cultural analogues of those “forgotten men and women” who have become estranged from the political establishment. Moreover, the power of celebrity can bring comfort, rather than just disdain, to the culturally forsaken, such as Gary Sinise’s outreach with soldiers and veterans through his Lt. Dan Band or Dolly Parton’s efforts for childhood literacy. I have also been moved by efforts such as the Joe Bonham Project connecting illustrators with Wounded Warriors as they undergo rehabilitation, shining a light on the hidden faces of war.

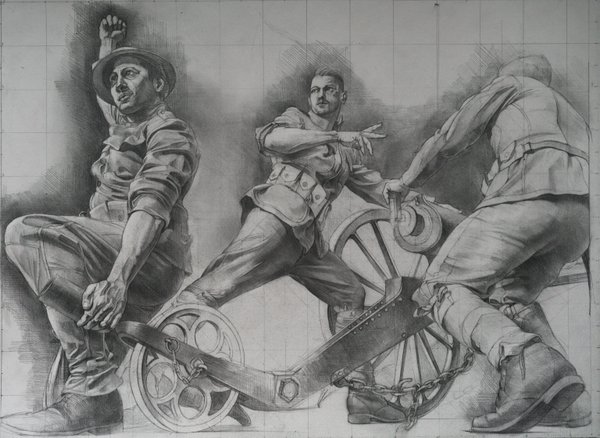

Concept for Wheels of Humanity, a sculpture by Sabin Howard to be displayed

at the National World War I Memorial in Washington, D.C

A final mention should go not only to our culture’s geographic outliers, but also to those who have been aesthetically pushed aside. What I mean are to those many artists, undoubtedly a majority of the country’s artists, whose creative urge has driven them beyond the pale of narrow, establishment style. You might have your pick of this category, but it would include every artist who does not fit within the Happy Meal of Contemporary Art now served up the same way across the country (Gerhard Richter burger; Kehinde Wiley fries; Jeff Koons toy). So consider the religious artists, the plein-air painters, the formalists, the classical realists, and the many, many others now on the outside looking in.

All this will be a bitter pill for the art world to swallow. “Trump lost the art vote by a wide margin,” writes Ben Davis. A critic on the Left, Davis it should be said contributed the most comprehensive coverage of artists across the political spectrum this election season, including the activism of Scott LoBaido. “The entire cultural establishment . . . threw its weight behind Hillary Clinton (or at least against Donald Trump) in the final stretch of this campaign.” Still, Davis concedes, “mainstream culture failed to be the decisive factor where it was needed. It is even likely that this anti-Trump unanimity may have helped give a false sense of his weakness.”

Davis is right when he suggests that the “dynamic of this election should raise some critical questions on the limits of cultural activism.” It is a conclusion with which the world of culture must reckon as it considers art in the age of Trump and the best application of its creative and institutional energies in a divided landscape.