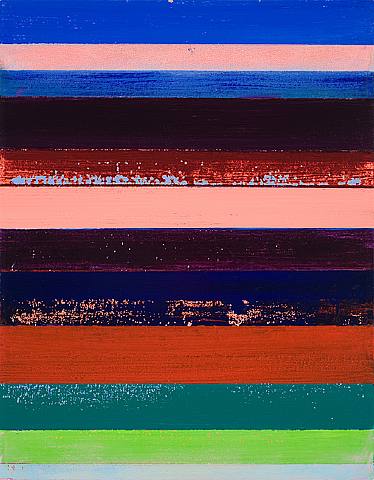

Robert Swain, Untitled (2007), All rights reserved © Robert Swain

THE NEW CRITERION

November 2010

Gallery chronicle

by James Panero

You can’t help but feel a little bad when visiting the Times Square Gallery and MFA studio building of Hunter College. There are physiological reasons for this. Sandwiched between Tenth Avenue and the appropriate-sounding Dyer Avenue on West 41st Street in Manhattan, this gallery space is off-off Broadway but very much on every major traffic artery leading into the Lincoln Tunnel. To get there requires the assistance of several traffic cops to hold back the cloud of soot barrelling towards Jersey. Then there is the greeting you receive once inside. When the Iron Curtain fell, the apparatchiks appear to have brought their vision of proletarian utopia to the City University of New York, the overlords of Hunter College. The dismal display of old turnstiles, “security desks,” and chipped industrial paint in the Hunter Times Square lobby recalls détente-era Leningrad.

But make a sharp right, pass through another door, and the surroundings suddenly change. Here the students, faculty, and private supporters of Hunter’s art department have carved out a remarkably pristine sanctuary for their exhibitions; seeing it made me feel lousy for a different reason. The Hunter department, part of it anyway, represents a last holdout for the study of pure color painting. A division of teachers here can trace their lineage through Josef Albers back to the German Bauhaus. Today they represent the Masada of color theory, pushed into a small settlement at the heart of Dumpsville. Now it has been reported that their godforsaken building, a holdout with its loft-like space, will soon be shuttered, thanks to the superior wisdom of the cuny hive-mind, and the department scattered to other sites.

If so, the Hunter Times Square gallery is going out with a bang. For the first time in memory, the sprawling space has been dedicated to a survey show of a single artist. “Visual Sensations: The Paintings of Robert Swain: 1967–2010” presents fifteen gallery rooms of color work by the longtime Hunter professor in an exhibition curated by his colleague Gabriele Evertz, a pure color painter I wrote about here in June 2009.[1]

While not a direct heir to Albers, Swain nevertheless landed his position in the Bauhaus-influenced Hunter department back in 1968 and has been teaching there since. Evertz earned her masters degree from Hunter in 1990 before rising to associate professor. Okay—so the curator, the artist, and the exhibition space are all part of the same institution. One might resent the incestuous relationship were the exhibition not so well done and so necessary. You would not see this show mounted anywhere else. The scale of the work alone is daunting. Few other spaces could accommodate it. Almost all of the paintings are six, seven, or eight feet tall. One painting is ten feet high by thirty feet long.

Beyond size, such a show must also contend with the unpopularity of its subject matter—color. Decorative, full of secrets, operating on its own terms, color has never had an easy go of it in the history of modernism, contrary to what one might assume. William Agee describes some of the reasons for color’s low caste in his excellent catalogue essay for the show. Despite a blip of popularity in the late 1960s during the rise and fall of Optical (Op) Art, pure color art, with its minimalist tendencies, has increasingly found itself at odds with the maximalizing tastes of the contemporary scene, where work is expected to refer to everything but itself. In our current climate, I doubt any other gallery would have cared to mount Swain’s expansive show. Their loss, our gain. “Visual Sensations” is one of those imperative exhibitions that no one wants to show but we still have the privilege to see.

In the mid-1960s, between studying with the American cubist Karl Knaths in Provincetown and at the American University in Washington, Swain worked as a guard in The Phillips Collection. Duncan Phillips had been attuned like few others to the color-rich artists of the modern movement, including Pierre Bonnard, Henri Matisse, and Milton Avery. Seeing the masterpieces of his collection sent Swain on a lifelong study of self-education into the nature of color.

The art that resulted from Swain’s studies conveys a didactic sensibility. Swain is a color artist but not an Op artist, at least not someone set on exploiting color’s destabilizing effects through the pairing of complementary colors and other techniques. Dispensing with the Op Art book of tricks, Swain set about exploring a color system of his own devising, made up of approximately 5,000 color components, which he applied to canvas in generously large grids of graded hues and values.

At his best, Swain is the process painter of color. Elsewhere this month, a exhibition at Minus Space in Brooklyn, an alternative private gallery venue dedicated to reductivist art, will focus on the process of Swain’s work by displaying his studio materials, color charts, samples from his paint library, plus mixing spoons and other ephemera. “Robert Swain, Primary Research” will run through December 4.

The conclusions of Swain’s paintings did not always live up to the processes that created them. A thirty-foot-long painting better be worth it, but one suspects the large scale of some of his work was an attempt to amplify the energy of a low-powered program. Today his tile-like paintings from the 1970s and early 1980s recall a benign computer screensaver or maybe the mosaic scrim of the Altria corporate logo. While one may pick up some interesting color effects up close, the overall compositions are too reserved, receding into bit-mapped space rather than coming forward in more active engagement. Several works from the late 1980s and 1990s, based on the proportions of the golden section and spiraling out from one corner of the canvas, are somewhat more present, in part through the rough texture of the paint built up through multiple layers of gesso.

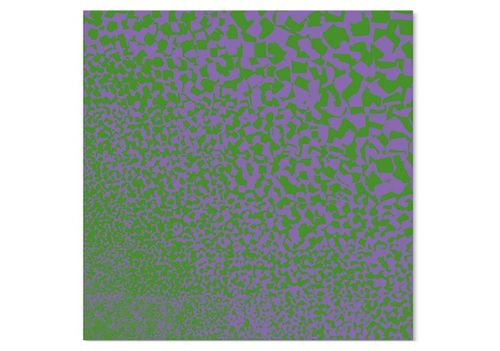

A few years ago, Swain himself started to feel his paintings had become too passive. Working through a lifetime of color discoveries and a desire to push them forward, he changed up his program to stunning effect. His latest paintings are the revelation of this show. Several of them are here to make a visit worth it, and they would mean far less without the context of work leading up to them. Returning to the active brushstroke he first used in his earliest work in the 1960s, Swain merged the structure of his grids and spirals with a newly developed system of daubs of pure color that grow in size across the field of the canvases. The results are wild, organic growths of pure color painting, daring and contemporary while recalling Abstract Expressionism. Color art without the masking tape? For someone quarantined for much of his career into perfect squares and rectangles, Swain has a daring free touch, and the results are fantastic. The energy of his brushstrokes has supercharged his color program. The effects, still totally controlled, now seem to emerge organically out of the work itself.

In September, a profile of the hipster artist Dan Colen that appeared in The New York Times would have us believe a Gagosian prankster working in bubble gum is the heir apparent to Jackson Pollock. Jack Shainman Gallery, Mary Boone, are you listening? I am here to say that a very different story is now being told at the Hunter Art Gallery, and that Robert Swain has a better claim to that title.

The New York gallery scene has a way of offering up nice coincidences. Now on view at Danese gallery is a four-decade survey of grid paintings by Julian Stanczak, perhaps the canonical painter of Op Art (the term was coined for one of his shows in the 1960s).[2] Born in Poland in 1928, Stanczak now lives and works in Seven Hills, Ohio. There’s a move that has one of those only-in-America rings to it, especially when you consider that, in the interim, Stanczak passed through Iran, India, and Pakistan as a refugee with the Polish Army-in-Exile in 1939, was interned at a Soviet concentration camp in 1940, and lived in a Polish resettlement community in the jungles of British Uganda in 1942. He emigrated to the United States in the 1950s and earned a BA from the Cleveland Institute of Art and an mfa from Yale, where he studied with Albers and Conrad Marca-Relli, and became a citizen in 1956.

The Op of Stanczak’s art is as much alchemy as science. Even with their taped lines and checkerboard patterns, his compositions can be magically powerful—emotive rather than emotional work from an artist who lost the use of his right arm in Siberia. His grids, with layers of carefully graded squares and lines, are built up so that the optical effects are maximized while the mechanics are tucked from view. Stanczak is less interested in revealing the process of his art than in presenting a product with the greatest punch and sparkle.

Most of the paintings here are constructed around a central axis. The colors radiate and rotate out of the heart of the work, sometimes pushing out, sometimes drawing us into perceived space. The grids, meanwhile, stitch the work together, containing the pulsating colors in their weave and giving the compositions a classical order.

Now in his eighties, Stanczak offers up two new red paintings that are the best and most assured works in the Danese show. In Echo 1 and Echo 2 (both 2010), he dispenses with his more fussy pattern systems and creates two warm and glowing works with subtle touches. At a time when the art world seems to listen more than it looks, here are paintings that are unabashed in their high-definition glory.

A final word about one of our own. In October, at Jill Newhouse gallery, Karen Wilkin organized an exhibition of drawings from a number of contemporary artists.[3] The show will be down by the time this issue comes out, but the gallery will still offer its excellent online catalogue on its website, and a selection of work from each of the artists will remain available to view at the gallery.

Wilkin casts a wide net to assemble “a group of works by artists whose efforts I am engaged and stimulated by . . . born from a desire to reflect the breadth of what is happening in studios today.” Some of the works, like the luxe bathers in charcoal and ink by Graham Nickson, or Fulvio Testa’s misty landscapes in watercolor, may be familiar to readers. Several others will not be. Enrico Riley is a young artist who maps star constellations in graphite on graph paper. Louisa Waber spins intimate webs in watercolor and pen. From Kikuo Saito’s black oil smears on found paper to Wendy Mark’s monotypes of scumbled clouds, the power of these works comes from their ability to convey a sense of touch. Connected through the eyes, the artist’s hand starts to feel like the viewer’s own.

[1] “Visual Sensations: The Paintings of Robert Swain, 1967–2010” opened at the Hunter College Times Square Gallery, New York, on October 7 and remains on view through November 13, 2010.