THE NEW CRITERION, February 2026

On “Declaring the Revolution: America’s Printed Path to Independence,” at the New-York Historical Society.

The nation’s semiquincentennial will provide many opportunities to revisit America’s founding. A small but enthralling show now at the New-York Historical Society deserves to be a foundational first stop. “Declaring the Revolution: America’s Printed Path to Independence” draws on the extraordinary collection of the philanthropist David M. Rubenstein.1 It tells the story of American independence through sixty documents that forged national resolve in a concise and compelling presentation. Curated by Mazy Boroujerdi, with detailed labels and a well-conceived arrangement of material, the one-room exhibition lays out the path to war and reveals the long road to American independence through the primary documents that took us there step by step. (A side note: now doing business as merely “The New York Historical,” the 222-year-old society is one of several institutions sadly struck with brand aphasia.)

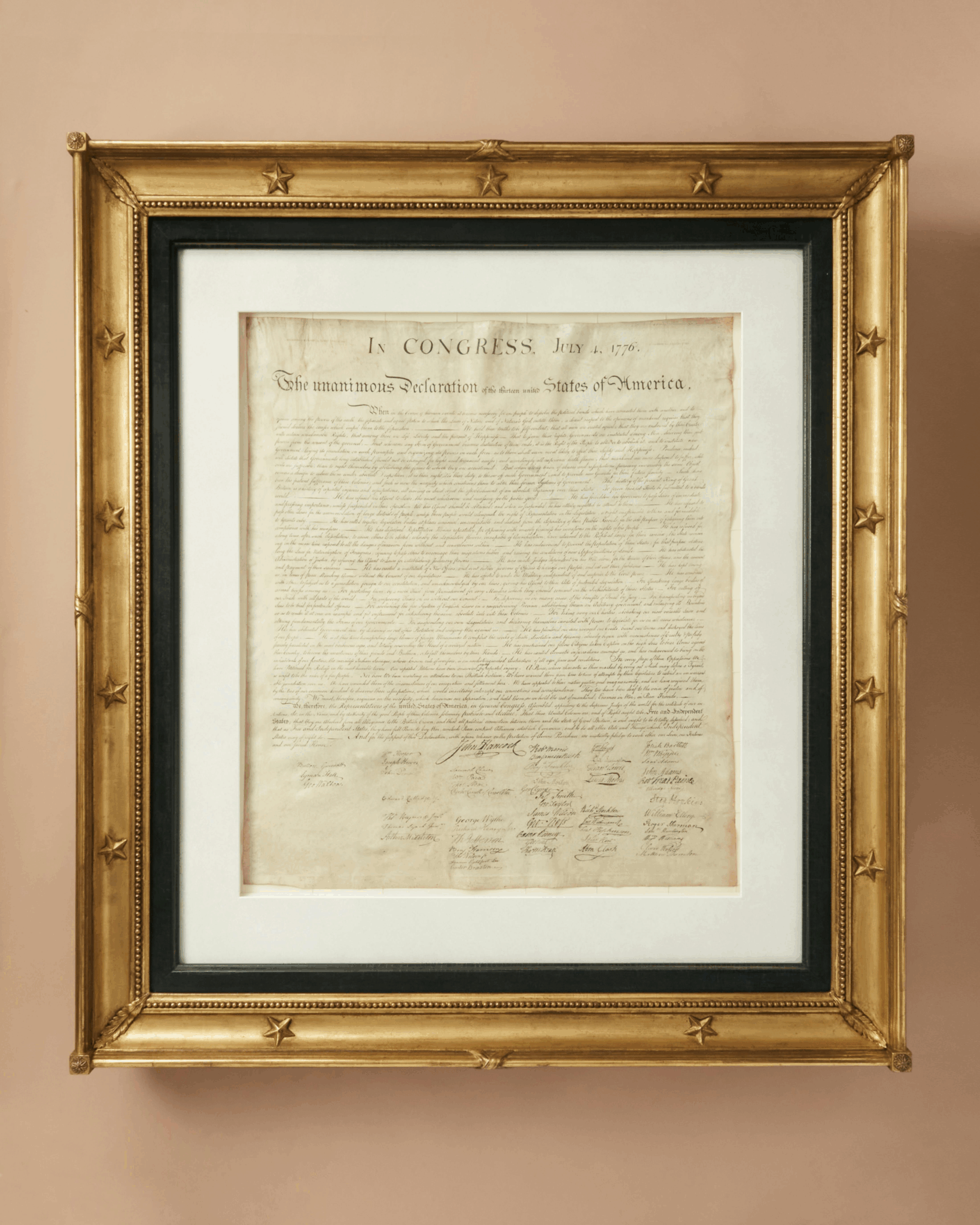

“The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants,” wrote Thomas Jefferson. So too must we refresh our understanding of these revolutionary materials. Take the Declaration of Independence. A well-recognized copy serves as the center of the historical society’s display. It may come as some surprise that the edition we most associate with this primary object of civic veneration was not created on July 4 or even in 1776 but in 1823, as this example attests.

The original Declaration, drafted by Thomas Jefferson with additions from a committee of the Second Continental Congress that included John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, was composed in manuscript. Their language built on the brief statement of the Lee Resolution, approved on July 2, 1776, which resolved that the colonies were “free and independent States.” July 2 might just as well be America’s independence day, but it was the July 4 adoption of the full and finely wrought Declaration that gives us our anniversary date.

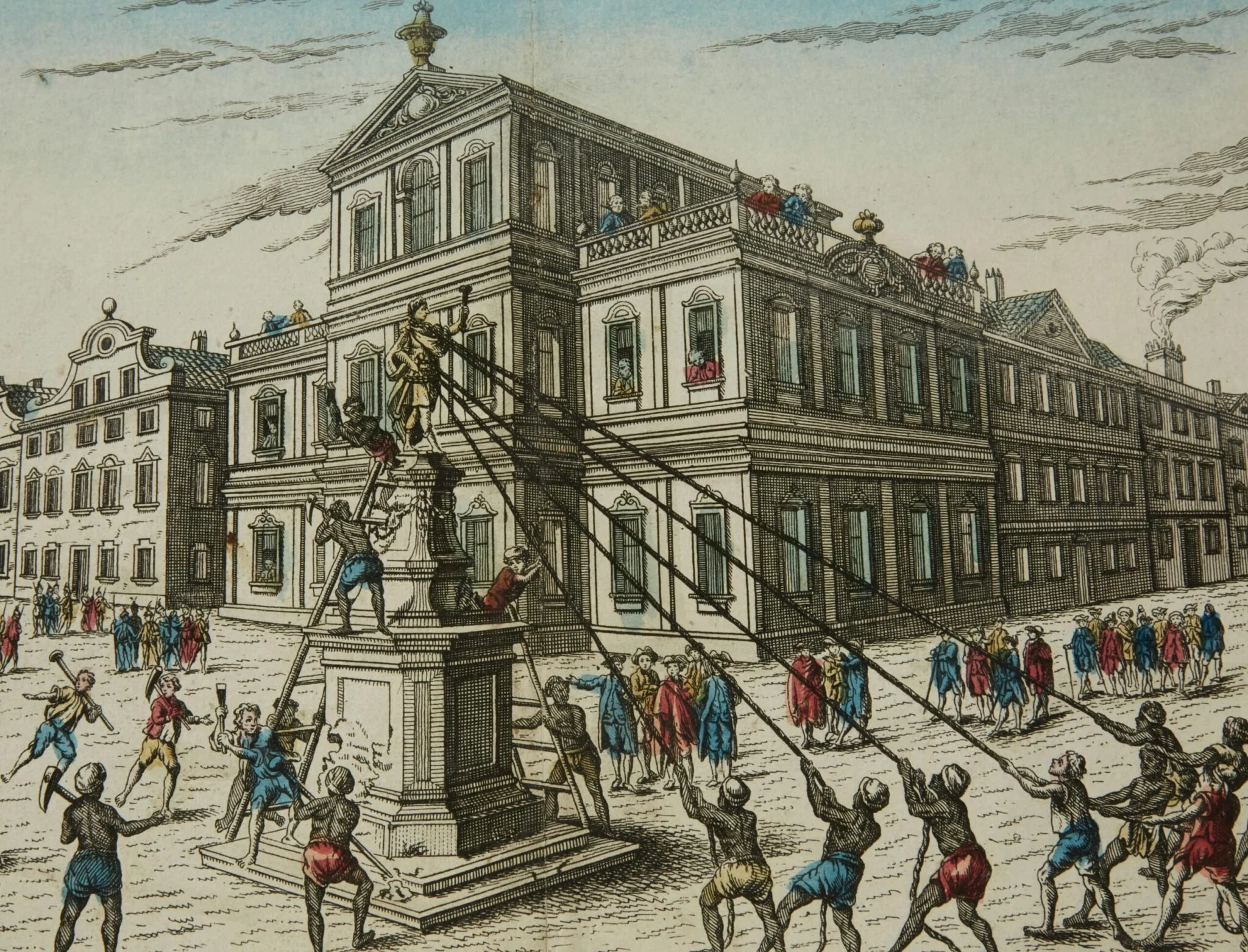

On July 5, the congress rushed this manuscript to the nearby print shop of John Dunlap to produce between a hundred and two hundred broadsides for distribution across the colonies and soon around the world. Four days later, after receiving a copy by mail from John Hancock, George Washington had one of these broadsides read aloud to his brigades assembled on the commons in lower Manhattan. Following this 6 p.m. announcement, a mob tore down the statue of George III in Bowling Green, an action Washington lamented for its riotous “want of order” (the statue’s lead was recast into musket balls for the Patriot cause).

The Declaration of Independence, 1823, Engrossed print copy. Photo: Vincent Dilio, courtesy of David M. Rubenstein.

Dunlap’s poster-sized broadsides are the earliest extant records of the Declaration. The original manuscript was lost during typesetting. On August 2, the Continental Congress memorialized its adoption by commissioning an engrossed, or handwritten and enlarged, version on vellum, most likely from the pen of Timothy Matlack. This is the edition that famously received John Hancock’s John Hancock, along with the signatures of the other delegates present. Since the New York Provincial Congress officially adopted the Declaration only in the interim on July 9, the opening lines were updated from a “declaration by the representation of the United States of America in general congress,” as the broadside reads, to “the unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America.”

The engrossed Declaration is the one now on display in a titanium case filled with argon gas at the National Archives Museum in Washington, D.C. Yet it too most likely is not the edition we most closely associate with this document. That’s because, even less than fifty years after its creation, the condition of the engrossed Declaration had already deteriorated. In 1820, John Quincy Adams, then the secretary of state, commissioned a set of two hundred official copies of the engrossed Declaration from the Washington engraver William J. Stone. Working with the document for three years, through a system of mirrors and tracing, and perhaps the lifting of some ink from the original document, Stone created a copperplate negative of the engrossed Declaration, including its fifty-six signatures. As with the original, he printed these facsimiles on vellum.

The Stone facsimile, a faithful print of the engrossed Declaration with wording that was once again legible, was distributed to federal and state repositories and the living members of the founding generation. Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, James Monroe, James Madison, and the Marquis de Lafayette each received two copies.

Today fewer than fifty known copies remain of Stone’s 1823 printing. Yet this is the version now most regularly reproduced since it reads closer to the original Declaration than the faded document bathed in inert gas in Washington. David M. Rubinstein, the cofounder of the Carlyle Group, the private equity firm, has collected the few Stone facsimiles in private hands and dedicated them to public display alongside his collection of other key American documents. We may never be closer to the Declaration than with his copy now on loan and available for detailed examination.

“Declaring the Revolution” makes a compelling case for the cause of American independence as a continuation of English rights and liberties. As represented by the other documents on display, the Declaration comes at the fulcrum of a two-decade-long conflict as history’s least revolutionary document of revolution. “Prudence,” it reads, “indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes.” Beyond its idealistic opening, the Declaration is mainly a legalistic enumeration of grievances, of a “long train of abuses and usurpations” with “repeated injuries” leading to a reluctant resolution grounded in law and custom. The great irony of American independence, and its greatest salvation, was its conservative assertion of English rights against an un-English monarch:

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Paul Revere, The Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street, Boston, on March 5th, 1770, Hand-colored engraving. Photo: Vincent Dilio, courtesy of David M. Rubenstein.

At the historical society, flanking the Stone facsimile to the left, is an edition of the Declaration of arguably even greater rarity and import. This is the version printed by the Pennsylvania Evening Post on July 6. It was the Declaration’s first truly public appearance, typeset from the broadside of a day before and available for “only two Coppers.” (Rubenstein purchased his copy at auction in 2013 for $632,500, the highest price then paid for a historical newspaper.) Immediately to the right of the Stone facsimile, the inclusion of a 1773 Slave Petition for Freedom feels forced. The document nevertheless serves to reveal the emancipatory impulse already in circulation at the time of revolution. “The divine spirit of freedom, seems to fire every human breast on this continent,” it asserts. The state of Massachusetts, where this petition was issued, abolished slavery seven years later.

In a center vitrine, in line of sight with the Declaration, are the documents and books that informed its ideals. Included here are copies of John Locke’s Second Treatise on Government, in an American printing from 1773. First published in 1689, this treatise arguing for the natural rights of “life, liberty and property” gained renewed attention in the revolutionary era. So too did Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan, here in a copy from 1651, laying the case for the social contract between government and the governed.

Fronting this display is Magna Carta, represented by an eighteenth-century engraved facsimile of the 1215 document preserved at the British Library. (It is noteworthy that the only thirteenth-century version of this document in the United States is currently at the National Archives Museum—there on long-term loan from David M. Rubenstein).

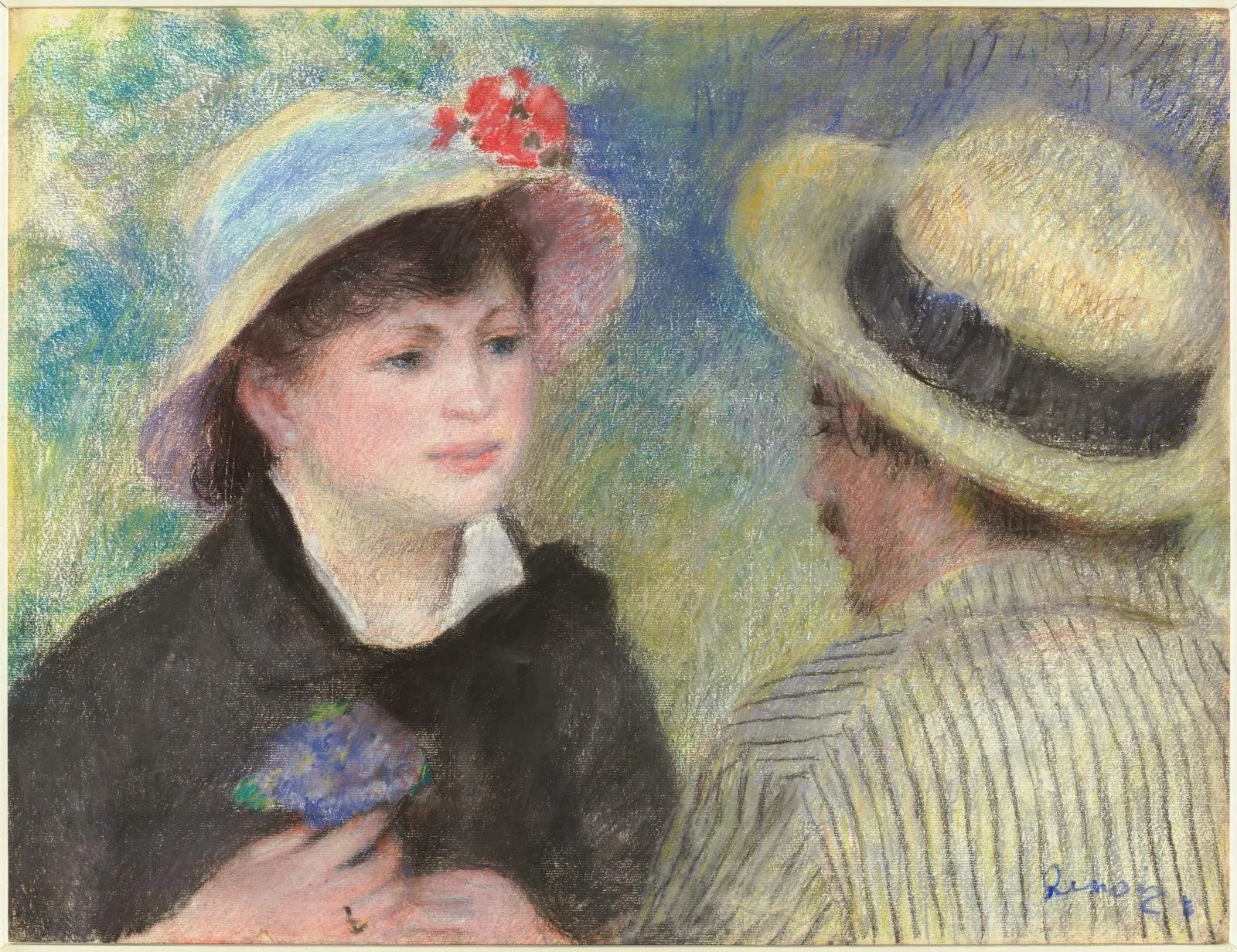

As with the liberal arguments that surrounded Magna Carta and later the issuance of the English Bill of Rights, here in a 1689 first edition, the colonists saw their cause as grounded in English law. Their struggle for redress, at first, came about as forms of isolated resistance and then as a united colonial civil war. At the historical society, this story begins to the left with a copy of the 1765 Stamp Act. The much-maligned taxation scheme, designed to underwrite the British military presence along the colonies’ extensive frontiers following the French and Indian War, was met with compelling counterarguments from several American voices. Benjamin Franklin’s testimony against it in the House of Commons in 1766 is here represented in a printed account of his four-hour-long examination. “No, never” would the colonists pay the duty “unless compelled by force of arms,” he declared. While that act was repealed, new British taxes led to civic disturbances culminating in the Boston Massacre of 1770, made all the more bloody in the colonial mind by Paul Revere’s contemporaneous engraving. As Massachusetts became a center of colonial insurgency to British military occupation, the first shot of Lexington and Concord in 1775, “heard round the world” (in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s famous phase of 1837), brought the conflict into open rebellion.

A hallway wall, just around the corner from the main gallery and easy to miss, includes documents related to the prosecution of the Revolutionary War divided between its northern and southern theaters. The path to American independence was paved by more than just the writings of history’s most motivated lawyers. It involved nearly a decade of armed conflict and more losses than wins for the American side. These displays lay out the accounts, records, and maps of the campaigns while also revealing the rising international interest in American independence. Traité d’Amitié et de Commerce, Conclu entre le Roi et les États-Unis de l’Amérique Septentrionale, reads a vital 1778 treaty of French support for the revolution. Le Général Washington Ne Quid Detrimenti capiat Res publica is the title of a French print from circa 1780.

“Declaring the Revolution” reveals the indomitable spirit of ’76 that buoyed the Patriot cause to force the surrender of Charles Cornwallis, the commander of British southern forces, at Yorktown on October 19, 1781, and brought about the Definitive Treaty between Great Britain, and the United States of America, Signed at Paris, the 3rd Day of September 1783. The astonishing victory continues to inspire the spirit of liberty and recalls the debt of sacrifice made in the name of freedom.

“Declaring the Revolution: America’s Printed Path to Independence” opened at the New-York Historical Society on November 14, 2025, and remains on view through April 12, 2026. ↩