James writes:

When old timers like Holland Cotter and Peter Schjeldahl are grumbling about art fairs, it's time to give the art fair another look. Through Monday, the organizers behind London's Frieze Art Fair decided to take on The Armory Show and March's "art fair week" with a New York appearance that aims to push the reset button on what an art fair can be.

Can you hear me now? Here's the view from the line for the special ferry to Frieze at 35th Street and the East River, with functioning jackhammer a mere ten feet away.

Located on Randall's Island, the Frieze fair is an advertisement for New York's great waterways. No surprise that Mayor Bloomberg has been Frieze big booster and was seen taking his time at the opening.

Here is the Frieze water taxi, which is like The Circle Line for Eurotrash. Take me to the Giardini!

No art fair offers a more curated experience than Frieze, from its stripped-down website to its (supposed) advanced ticketing requirement.

Here is John Ahearn's South Bronx Hall of Fame (1979/2012), in which the artist produces casts of fair goers in homage to the 1979 sculptures he made in the South Bronx. This project space, which "functions as a tribute to the alternative spaces and galleries that were once vital for the artistic community but have now closed," reminds fairgoers there's more to art than commerce. I would have liked to have seen even more of them.

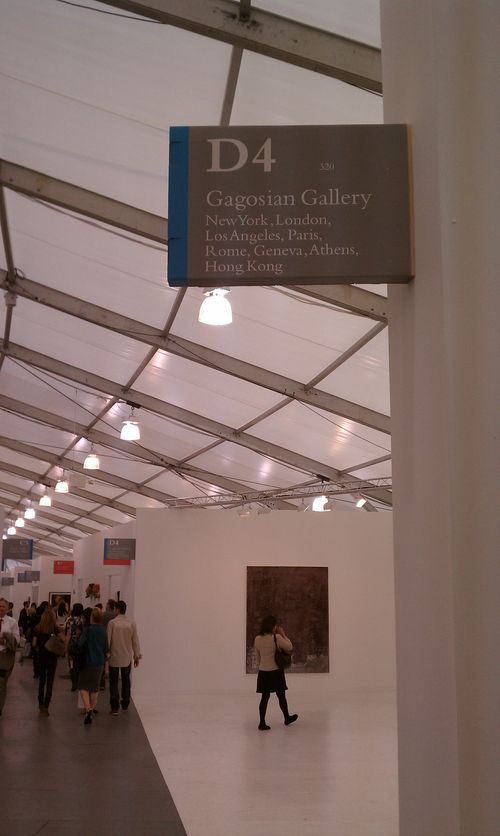

The Frieze tent, designed by the Brooklyn architectural firm SO-IL, maximizes natural light while also employing special lamps. Frieze feels like being inside an iPad. The cool factor may be why Gagosian made its first New York art fair appearance at Frieze as one of the 180 exhibiting galleries--but couldn't its sign above have just said "the universe"?

"Sometimes you feel like a nut." Frieze wasn't free of attention-grabbing gimmicks. Here is a mannequin nut-cracker...

....but for the most part the fair played it cool. If the Armory Show was all flash, Frieze is all texture. The concrete sculptures above, which must be anchored to the earth through holes cut in the plywood floor, probably never looked better.

If Frieze was out to civilize the world of art fairs, it didn't stop at the front door. The fair's outdoor sculpture park made even the Triborough Robert F. Kennedy Bridge look good.

Randall's Island can seem like a breathtaking setting straight out of classical landscape, save for the psych ward at left.

Whew! This injection of reality is in fact an installation by curator Tom Eccles and artist Cristoph Büchel.

And here's the VIP south entrance to Frieze. Sure you could arrive by limo, but the food trucks are all parked where the buses and ferries come in at the other end. Inside the fair there's also hipster-than-thou food options like pizza from Roberta's. Getting to Frieze (and talking about getting to Frieze) is part of the experience. The water taxi is a treat, but the buses that leave from the 125th Street 4-5-6 Subway station are even more convenient.

On view through Monday, Frieze plays it cool as the competition overheats.