Typhoon Camille

by James Panero

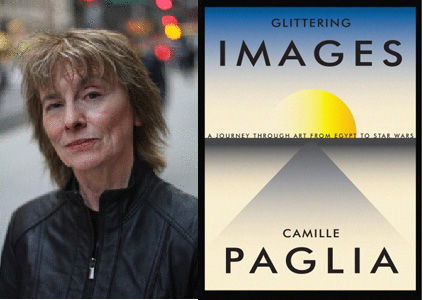

A review of Glittering Images: A Journey Through Art from Egypt to Star Wars, by Camille Paglia (Pantheon, 202 pp., $30)

When Camille Paglia published Sexual Personae, her 1990 study of “Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson,” she became an unexpected combatant in the cultural wars. In a 1991 cover article that resembled a poster from the Wild West, The Village Voice plastered a picture of Paglia alongside mugshots of Roger Kimball, Dinesh D’Souza, Robert Brustein, Eugene Genovese, and Allan Bloom. The newspaper accused Paglia of being a “counterfeit feminist” who was “wanted for intellectual fraud.” The second-wave feminist Sandra M. Gilbert similarly wrote in The Kenyon Review that Paglia “loathes liberalism, egalitarianism, feminism, and Mother Nature.” Paglia was nothing if not primed for the fight. In her book, and in the interviews and articles that surrounded it, she attacked French post-structuralist theory and called out American feminist leaders as “drones,” “Stalinists,” and “sanctimonious . . . PC divas.” Like Susan Sontag, her one-time idol, Paglia became an intellectual sensation, and she made the most of it.

The Left saw Paglia as an enemy from within, a “dissident feminist” who happened to be a lesbian and atheist. For the Right, she was an unpredictable ally. Her tastes could range from the sacred to the secular to the commercial to the profane. “I would be someone who would look into the latrine of culture, into pornography and crime and psychopathology,” she wrote in her essay collection Vamps and Tramps, “and I would drop the bomb into it.” In her column for Salon.com, she could be the defender of high culture one minute, the oracle of Madonna (or Lady Gaga) the next. Her final chapter inSexual Personae was titled “Amherst’s Madame de Sade: Emily Dickinson.”

Such seeming idiosyncrasies are part of her fascination. The contrarian streak continues in her latest book, Glittering Images: A Journey Through Art from Egypt to Star Wars, a defense of the life of art that manages to be both enlightening and maddening.

“Modern life is a sea of images,” she begins. “Our eyes are flooded by bright pictures and clusters of text flashing at us from every direction.” Therefore: “We must relearn how to see.” For Paglia, great art can be the teacher, a visual sutra to clean the lenses of our overstimulated eyes. “The only way to teach focus is to present the eye with opportunities for steady perception—best supplied by the contemplation of art. Looking at art requires stillness and receptivity, which realign our senses and produce a magical tranquility.”

In her opening chapter, she makes an energetic appeal to the canon: “Museums have embraced publicity and marketing techniques invented by Hollywood to attract large crowds to blockbuster shows, but the big draw remains Old Master or Impressionist painting, not contemporary art.” Then comes the hook: “George Lucas is the world’s greatest living artist . . . nothing I saw in the visual arts of the past thirty years was as daring, beautiful, and emotionally compelling as the spectacular volcano-planet climax of Lucas’s Revenge of the Sith (2005).” On the face of it, these two arguments are contradictory. It’s odd to condemn museum blockbusters only to praise a Hollywood blockbuster. Nor is it easy to understand how the needs of a culture “flooded by bright pictures” and in need of “steady perception” might be served by the “spectacular volcano-planet climax” of a billion-dollar film franchise.

A cynic might call such rhetoric clever marketing. A book of art criticism could do worse, publicity-wise, than hitch its wagon to Hollywood. One can only imagine how other books might have done if their authors had sprinkled similar pixie dust over their titles. The Closing of the Jedi Mind and From Dawn to Darth Vader might have flown off the shelves. There might also be something smug in assuring your reader that the summa of great art is—look no further!—right there in your Netflix queue.

But I’m tempted to give Paglia the benefit of the doubt. A line of aesthetic decadence runs through all of her chapters. She embraces art’s mystical power and rejects academic materialist interpretation. “Marxism sees nothing beyond society,” she writes. “Marxism lacks a metaphysics—that is, an investigation of man’s relationship to the universe, including nature.” It’s therefore possible that Paglia really does believe Revenge of the Sith is the most “daring, beautiful, and emotionally compelling” work of visual art she’s seen in the last 30 years. At the least, it’s an interesting point to consider—one that her decadent hero Oscar Wilde, or certainly Andy Warhol, might have appreciated.

Her book is rife with other contradictions, leading one to conclude that Paglia’s passions often get the best of her arguments. At one point she praises the Beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti for having the “perspicacity and courage to exhort the arts community to renounce its infantilizing dependence on the government dole.” A page later, she seems to praise “cautious optimism about increases in federal arts funding.” She admires and defends “Robert Mapplethorpe’s homoerotic, sadomasochistic photographs” but calls out the art world’s defense of these photographs as “demagogic.” She seems to bemoan the rise of Pop Art, which turned Abstract Expressionism into “the last authentically avant-garde style in painting,” but she then praises “Pop Art’s happy marriage to commercial mass media.”

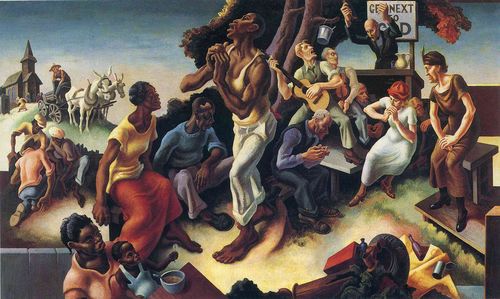

Sandwiched between such statements and the “Egypt” and “Star Wars” of Glittering Images are 27 digestible chapters that look at individual works of art: some well-known masterpieces, others (of course) more idiosyncratic. One could do worse than absorb the survey of Western art presented in these 190 pages. Here we find Paglia’s bewitching eye, matched with her gift for language, at its best. “French rococo interiors have clarity, yet they are suspended, elusive, unresolved,” she concludes in her chapter “Swirling Line.” “So much pretty motion, and yet so much golden paralysis.” In “Arctic Ruin,” she writes how The Sea of Iceby Caspar David Friedrich evokes “the stainless-steel spires of Art Deco skyscrapers or the cantilevered concrete slabs of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater.”

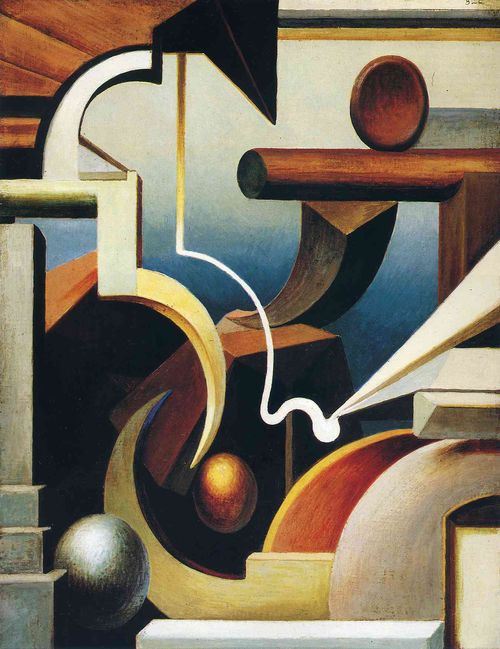

Her most unexpected selection also makes up her most interesting chapter: “Dance of the Mind” looks at Portrait of Doctor Boucard, a 1929 art deco painting by the relatively unknown Tamara de Lempicka, “a liberated new woman with her own agenda,” writes Paglia, “which included cocaine-fueled bisexual adventures in seedy riverside bars.” One reason we’ve likely never heard of Lempicka is that her work “does not support the ruling paradigm of art as leftist resistance.” Instead, the artist offers up a “hallucinatory resynthesis of classic artworks,” where Boucard’s heroic “eyes rake the horizon as if he were a ship’s captain on a voyage of discovery—an effect heightened by his rippling coat flap, his ballooning lapel, and the silvery collage of sail-like Cubist planes behind him. It’s as if he feels the wind of history at his back.”

Paglia writes with her own following breeze. She is a critic to be enjoyed under full sail, just as long as you don’t get blown overboard.