Owners of Mast Brothers Chocolate, Michael and Rick Mast, at their Williamsburg store.

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

June 24, 2012

Hail to the Hipsters

by James Panero

Love them or hate them, they are essential to our economy

They are one of New York City’s most universally reviled species: hipsters. You know who they are, but almost nobody wants to admit to being one.

Hipsters know things the rest of us don’t, and they want us to know that they know it, too. They are cooler than you or I. They were cool before it was cool. Or maybe they are ironically cool, cool after it was cool. One thing about hipsters is certain: As the latest youth tribe, they can be particularly annoying.

What's less known about hipsters is that they are busy saving New York. They’re not the lazy trust-fund brats of stereotype but the entrepreneurs of an amazing resilient city economy. The next time you see one, think twice before scoffing; he or she just might be your next employer.

What’s a hipster? If you have to ask, you’ll never know.

“The hipster can construct an identity in the manner of a collage, or a shuffled playlist on an iPod,” observes Christian Lorentzen. They take “your grandmother’s sweater and Bob Dylan’s Wayfarers, add jean shorts, Converse All-Stars and a can of Pabst,” says Time. They are the “soldiers of fortune of style,” writes Elise Thompson.

Hipsters are too cool for definitions, but in New York we know them when we see them. They have the facial hair of 19th-century weightlifters. Wearing too-tight jeans, they ride “fixie” bikes with no brakes. They populate the L train, and when Williamsburg and the East Village became too officially cool, they drifted to Greenpoint and Bushwick. They keep their own beehives and make their own beer.

They live in gentrifying areas of Brooklyn like they’ve been there forever even if they moved in last month. They are the ones “in newsboy cap and tweed britches, pedaling his penny-farthing to a north Brooklyn industrial space to make handcrafted nano-batch sweetmeats,” writes Benjamin Wallace in New York magazine.

Or as the NBC nightly news anchor Brian Williams famously ranted in December 2010: “There are young men and women wearing ironic glass frames on the streets” selling cheeses at “flash artisanal markets” and making “simple beads at home” to trade “for someone to come over and start a small fire in your apartment that you share with nine others.”

But the traits that make hipsters so laughable are also the ones feeding New York’s new economy. Hipsters may appropriate the styles of earlier youth movements — the beatniks, hippies, punks and slackers — but they strip away the antisocial and anticapitalist qualities of these groups and replace them with entrepreneurial drive.

Rob Horning calls hipsters “a kind of permanent cultural middleman in hypermediated late capitalism, selling out alternative sources of social power developed by outsider groups.” Hipsters have therefore become New York’s most active innovators, using the density of the city and its underused resources to spread and develop new ideas.

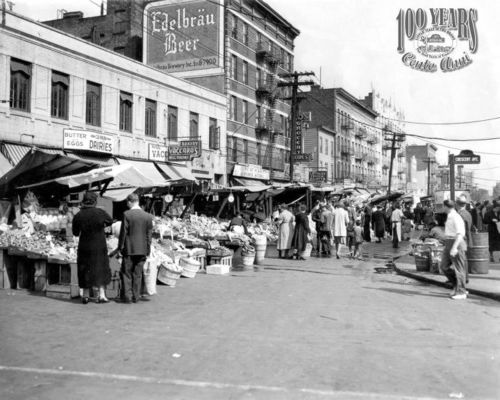

The artisanal revolution of Brooklyn is one example. As transitional manufacturing has left the outer boroughs, young producers have moved in to make everything from chutney to beer, hand-painted axes to small-batch mayonnaise.

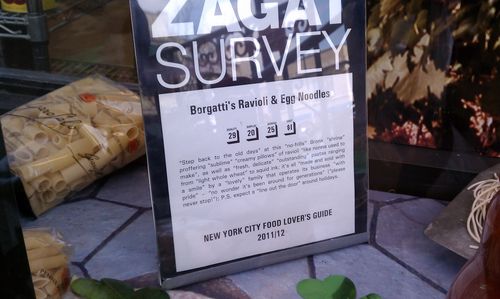

And what some hipsters make, other hipsters take. Founded in 1988, The Brooklyn Brewery brought craft back to Brooklyn before it was hip. Now located in an expanded facility in Williamsburg, Brooklyn Brewery is a multimillion-dollar operation that claims to export “more beer than any other American craft brewery.” Numerous other beer makers have followed suit, including Sixpoint, founded in Red Hook in 2004 and now a hipster favorite. If you want a job here, the company asks, “Do you homebrew? If the answer is ‘no,’ then start homebrewing and we’ll talk afterwards.”

Sure, hipsters can be pretentious. They can also be funny. In 2011, the bearded brothers who own Brooklyn-based Mast Brothers Chocolate employed a handcrafted schooner to sail twenty tons of their cocoa beans from the Dominican Republic to Red Hook. It was the first time since 1939 that a commercial vessel delivered cargo into New York harbor under sail.

“The easiest way to make it local is to sail it,” proclaimed Richard Mast. “True American optimism right here.” He’s right. Today, thanks to hipsters like him, the label “Made in Brooklyn” is a mark of quality for food the way “Made in Italy” once was for clothing.

In Paris, as hipster-style food trucks have rolled into the French capital, the best thing they now call cuisine is “très Brooklyn,” a “term that signifies a particularly cool combination of informality, creativity and quality,” according to a recent report in The New York Times.

Hipsters are classical capitalists, opposed to both big business and big government. In “Don’t Mock the Artisanal-Pickle Makers,” an article in The New York Times, Adam Davidson writes, “It’s tempting to look at craft businesses as simply a rejection of modern industrial capitalism. But the craft approach is actually something new — a happy refinement of the excesses of our industrial era plus a return to the vision laid out by capitalism’s godfather, Adam Smith.”

Consider the rise of New York’s latest arts neighborhood in Bushwick. First pushed east from SoHo and later priced out of Williamsburg, thousands of artists recently moved there into lofts converted from old factory floors. They set up studios. Many ignored city regulations and began to live there.

Without the support of the art establishment of museums, auction houses, commercial galleries — or city government — these artists built up their own commercial networks. They ran galleries out of their apartments and later small shops on the street. This past month, their sixth annual “open studios” weekend offered up more than 500 free venues, received headline attention, and included a Do-It-Yourself commercial art fair called “Bushwick Basel.”

While many of the artists here may not call themselves “hipsters,” their happy detachment from mainstream culture, their self-starting energy, their networking abilities and their love of craft have much in common with the pickle purveyors next door.

True hipsters never call themselves hipsters. The same goes for an industry that is now growing faster than any other in New York — 10 times faster than the overall change in city employment. Between 2007 and 2011, New York’s tech sector grew to overtake Boston’s to become the nation’s second largest after Silicon Valley.

Technology engineering may still center on the open spaces of the West Coast. What New York offers is hipster cool and an ability to develop technology into something people want to use.

The New York tech sector — focused between Union and Madison Square in an area sometimes known as Silicon Alley — is all about apps and social media.

Multimillion-dollar companies like Tumblr, Foursquare and Kickstarter are among the 500 or so recent New York tech startups to receive investor funding. Communal tech campuses have also opened in old warehouse buildings offering space for anyone with a laptop and a dream. The campus map of one such venue, General Assembly, list places for “concepting, fireside chatting, pillow fighting and reading and relaxing.”

Sometimes called “betaniks,” hipsters are developing and spreading these new technologies, becoming early adopters of innovations before the rest of us even know we want them.

It’s easy to see why many of us dislike hipsters. They can be obnoxious. Many of their ideas, their startups, their art galleries and their condiments will never catch on. But let’s face it: certain things will. Businesses will grow. Jobs will be created. Industries will emerge. All right here in New York.

So let’s raise a growler of cold brew coffee. Share the moment on Tumblr. Buy a painting out of a Bushwick apartment. And say hip-hip hooray for the hipster.