Dara and James write:

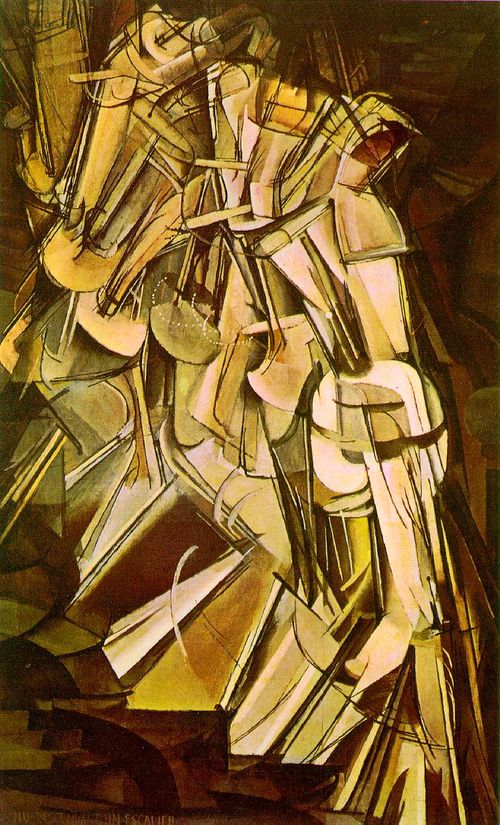

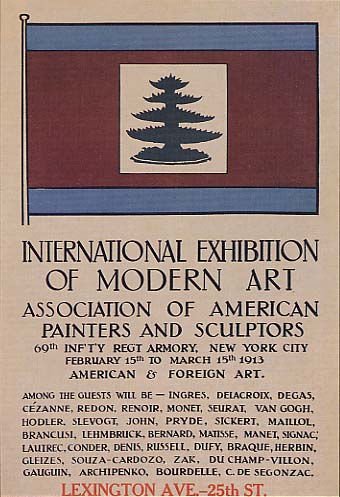

The history of modern art features many groundbreaking collaborations between artists and poets. "Inventing Abstraction," the exhibition now on view at the Museum of Modern Art, includes several examples of such collaborations. One favorite is La prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France, by the poet Blaise Cendrars and the painter Sonia Delaunay. More recently there was Breath, a collaboration in the early 1980s between the sculptor Christopher Wilmarth and the poet Frederick Morgan, who had translated seven poems by Mallarmé. Poets House maintains a collection of many additional examples.

The Bushwick nonprofit Norte Maar, which is dedicated to "collaborative projects in the arts," has now underwritten a number of publications bringing artists and poets together. When the artist Brece Honeycutt was selected for an upcoming project, she approached Dara to contribute original poetry (Brece had heard Dara read at Norte Maar's celebration of John Cage.) Their book is slated for publication this spring.

As Brece works through ideas for the book, she welcomed us at her studio in Sheffield, Massachusetts.

Brece works in an antique barn that was transported from Vermont and recently reclad in a new timber facade. The light above was repurposed from a nearby train station. (All photographs by James Panero.)

The light-filled workspace overlooks a small pond that used to be the town's skating rink.

Brece works in a variety of media. Spools of yarn, vintage washboards, books on flowers, and papery wasps nests are all integrated into her diverse practice.

Brece has many projects going on in her studio. Here she is at her loom creating a rag rug.

Brece spins and knits her own fiber sculptures.

For our collaboration, Brece is using various plants, vegetables, and objects to hand dye paper.

Brece makes her own dyes from leaves and plants she has collected in the area. Here the leaves are soaking in water, which will be used to stain the pages.

Goldenrod, drying in the attic, will be used for additional dyes.

Once Brece has the stains, she adds additional objects as resists and presses the pages together overnight. When she opens them up, she discovers how the foliage and other elements have left their marks on the paper.

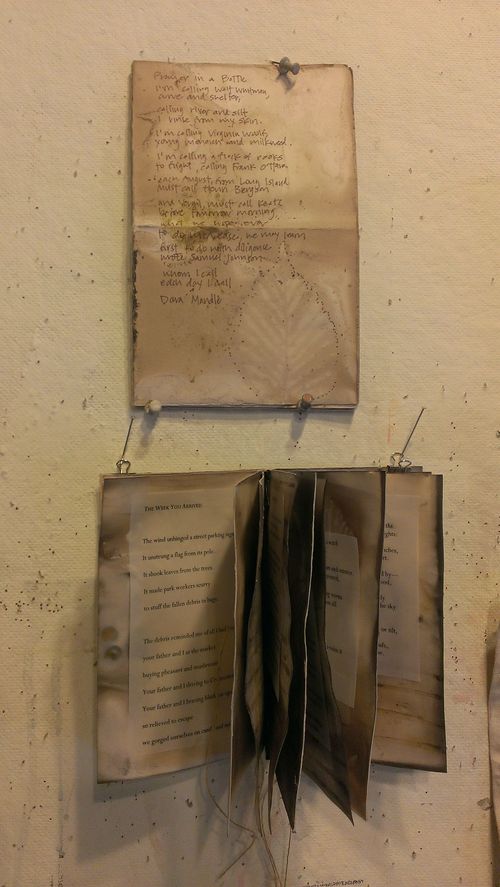

On one wall Brece has pinned prototypes for the book. Here Brece has written out one of Dara's poems on hand-made paper (above) and hand-stitched the binding of some pages (below). Dara and Brece are experimenting with different page formats and working through ideas of how best to translate Brece's handmade book art to multiple production.

Brece and Dara look over pages in production. Brece's stand-along paper sculptures hang on the back wall.

A panorama of Brece's studio.