THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

April 15, 2009

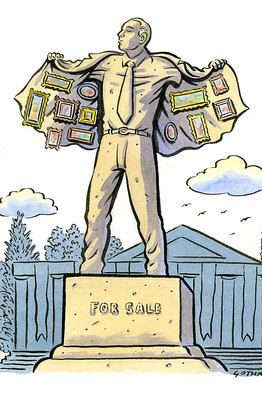

Another Museum Puts Its Collection on the Block

by James Panero

Another day, another deaccession. On March 23, after a "strategic review of its operations and capitalizations," the Montclair Art Museum in Montclair, N.J., announced a new "financial security plan." In what has become an all-too-common practice in the art world, this plan will include the sale, or "deaccession," of 50 works from the museum's permanent collection, among them a Jackson Pollock drawing valued at $300,000 to $500,000 and several Hudson River School and American Impressionist works with estimates ranging from $25,000 to $300,000, according to a prospectus prepared by Christie's. The auction house believes the sales will generate between $2.9 million and $4.3 million for the institution, which says it will use the funds for future acquisitions. Presented as curatorial housekeeping, but in fact motivated by financial exigencies, the Montclair sales -- if allowed to proceed -- will set another sorry example of an institution cashing out on art in the public trust.

p>Opened in 1914, the small, neoclassical Montclair Art Museum has long boasted an impressive collection of American art, with a sizable selection of work by Hudson River School painter George Inness, who settled in the town at the end of the 19th century. The museum has also acquired and displayed a large collection of Native American art and mounted critically acclaimed exhibitions. A show exploring the influence of Cézanne on American art, 10 years in the making, is scheduled to open this September. An exhibition of Wyeth-family paintings is now on view.

In the stewardship of its permanent collection, however, Montclair has left a more questionable legacy. The museum has often treated its record of local philanthropy as trade-in art. Nobody knows this better than Cherry Provost, a former trustee who grew up in the shadow of this suburban museum and still serves on the art committee.

"I've said it repeatedly: A museum is not a private collection," she maintains. Over the years, her words fell on deaf ears as the museum sold off one part of its collection after another. "We had a snuff bottle collection of the first order," Mrs. Provost says. "I tried to save it. We also had a fabulous collection of early American and English silver -- to die for! And we had some lovely sideboards. Really good American antiques. And it was wonderful to have a sideboard. Well, the sideboard went."

That wasn't all. This past January, the museum shipped off its 6,000-volume art library as a gift to a local college, Montclair State University -- one of its many emergency actions, which include layoffs and reduced business hours, designed to shore up expenses. The museum says it also plans to sell its costume and rug collections and is determining what to do with its sizable Native American holdings.

By narrowing or "refining" a collection through deaccession, a museum can perform a valuable function. It can free up from storage work that may be second-rate or repetitive and return it to the marketplace, there to be purchased by an individual or institution that could make better use of it. A museum can furthermore raise money in a restricted endowment from the sale, to be used for the purchase of art that might better serve its mission. Peer-review organizations such as the Association of Art Museum Directors issue guidelines that define such acceptable practices. The AAMD also forbids museums from using the sale of art in their permanent collections to pay for general operating expenses or to underwrite loans with the art on the walls. Such rules are designed to prevent museums from treating their art collections as ATM machines, sources for fast money that should have been raised and managed in other ways.

Even before the economic downturn, however, museums had been finding ways around AAMD in a power struggle between directors and trustees, who want to unlock the value of their collections, and the museum-going public, which feels betrayed by the institutions that are designed to preserve and honor donations.

Museums have claimed, for example, that the art in their permanent collections suddenly does not fit their mission statements, even if the work has been on display for generations. Museums have decided that certain works of art are of secondary importance because they are rarely shown, although this record of exhibition may merely reflect the taste of the curators. Museums have also declared themselves to be schools or libraries, not bound by the rules of AAMD. As permanent collections have been put up for sale, the auction houses, of course, have only profited from the row.

In 2006 the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, N.Y., sold $68 million of its collection of older art in order to raise its endowment for contemporary work, claiming the older art did not fit its mission statement. In December the National Academy Museum in New York sold two valuable Hudson River School paintings to fill a budget gap, proclaiming its primary status as an art school. In a case earlier this year that attracted national attention, the trustees of Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., announced plans to shut down the school's Rose Art Museum and sell off the entire collection to raise general revenue. Legislation now under consideration in New York state would codify AAMD's most basic recommendations into law, allowing for the possibility of greater enforcement.

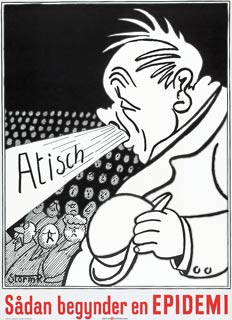

On Nov. 20, 2008, the Association of American Museums issued a statement designed to protect our nation's permanent collections in times of crisis: "There is increasing pressure on museums to capitalize their collections and to use them as collateral for financial loans to the museum. The AAM Code of Ethics for Museums requires that collections be 'unencumbered,' which means that the collections cannot be used as collateral for a loan."

Yet while museums are forbidden from "capitalizing" their collections, or using the value of their art as collateral for a loan, nothing in the AAM or AAMD rules explicitly prevents museums from selling their art along certain subjective guidelines, earmarking that revenue for future acquisitions, and then using the endowment money raised from the sales to back their loans. In both cases, art in the permanent collection has been capitalized. By taking the extra step of selling the art first, however, museums avoid the censure of AAMD while still underwriting loans that may go to general operating expenses or the next vanity expansion project.

This dangerous gap in the guidelines -- one that puts our nation's permanent collections at risk -- the Montclair Art Museum now plans to exploit. In 2001, the museum undertook a massive $14.5 million expansion that more than doubled its size and saddled it with debt. Now, as its overall endowment has dipped 25%, to $6 million from $8 million, the museum risks not having enough cash on hand to back its loans. That's where this deaccession comes in -- to raise cash to satisfy the requirements of its bank bonds. What's most troubling is that nothing on the books is designed to stop it, even though Montclair is liquidating art in its permanent collection to raise the aggregate collateral for its loans -- precisely what AAMD claims to oppose.

In an interview, Lora Urbanelli, the new director of the Montclair Museum and a member of AAMD, is upfront about the exigencies of her deaccession: "We took out tax exempt bonds at a certain time in our history. And when you do that -- we are diligently paying them off -- but whenever you do that, as part of the agreement, you agree to have a certain amount on hand in an endowment fund. At times when our endowment is flagging, we go below that line. So this is a creative way to keep the endowment full and to stay above the water line to grow our endowment for acquisitions -- just so we are in the good graces with the bond covenants. All the bank wants to know is that the endowment is a healthy one for the size of the institution. There's nothing untoward. There is nothing to hide. The deaccessioning that we're about to do has been more or less in the works for years. What we're doing now is considering an acceleration of a process. . . . The AAMD sees no problem with the way we are handling this situation."

Ms. Urbanelli presents her deaccession as a convenient way to solve her museum's financial problems. AAMD may never have anticipated this particular case of cash for art, but Montclair is nevertheless overstepping a more basic tenet of ethical conduct. The "decision to deaccession a work of art," according to AAMD, "should not be made in reaction to the exigencies of a particular moment."

The exigencies in the Montclair care are reason alone to question the sales, not to "accelerate the process," as Ms. Urbanelli maintains. If allowed to proceed, a museum will have found another way to monetize its collection without consequence, exposing another failure in the way our arts institutions police themselves. "I'm not saying every one of those paintings is a masterpiece," Mrs. Provost, the former Montclair trustee, notes of the auction, "but I've been involved with voting a lot of those paintings in. And there's a reason for every painting." As one museum after another announces deaccession plans as done deals -- "accelerations of a process" that take advantage of lax regulations -- patrons such as Mrs. Provost are right to become concerned. Montclair gives us another reason to worry about a future of art in the public mistrust.