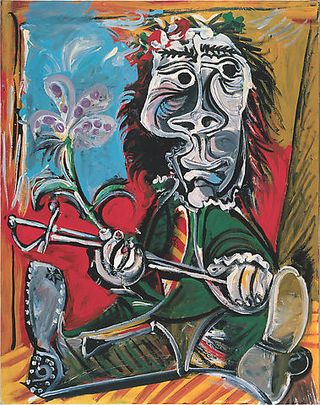

Hans Holbein, Portrait of Erasmus, ca 1530

ART & ANTIQUES

June 2009

Restoration Hardware

by James Panero

Marrying traditional knowledge with today's technology, art conservators are uncovering long-lost masterpieces.

In September 2000 art conservator marco Grassi was attending an estate auction in Paris with an old friend, a European private collector. In the warren of salesrooms at the Drouot Hotel, mixed in with the chipped crockery and worn sofas, was a small rectangular painting in a dusty glass case. It appeared to be a copy of one of the four or five famous portraits of the Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus that Hans Holbein the Younger painted from life. Yet Grassi grew intrigued by the quality of the painting. His friend asked his opinion, and on a whim he encouraged him to buy it.

When the hammer fell the next day the collector had acquired the lot for around $2,000, in line with its pre-sale estimate. Today, as a result of a decade-long process of restoration and research conducted by Grassi, the portrait, painted on linden panel around 1530, is generally accepted as a genuine, long-lost Holbein, one that would likely be worth tens of millions of dollars if offered for sale. "It was a wild shot," says the conservator, "but sometimes wild shots work out."

This past year, after a six-month review, the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, in Rotterdam, Netherlands (Erasmus' hometown), selected the painting for inclusion in an exhibition called Images of Erasmus. "Of course, we were very excited when we were offered this painting by Marco Grassi," says curator Peter van der Coelen. "I think the last (Holbein) portrait of this quality was discovered 150 years ago." Through the show the painting was subjected to scholarly investigation and compared to similar Holbein Erasmus portraits through loans from the Louvre, the Lehman Collection in New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Kunstmuseum Basel. Most experts now accept the painting as a Holbein on par with the Metropolitan and Kunstmuseum examples, if not quite on the level of the Louvre painting or the portrait of Erasmus at the National Gallery in London (the only major Erasmus painting by Holbein not in the show). The results were a coup for the conservator.

The Holbein rediscovery and other high-profile restorations have cast a new light on the private world of art conservation. In 1991, through an analysis of its under-drawing, the British scholar Nicholas Penny identified what was thought to be a Raphael copy as an original painting by the master. In 2004 the National Gallery in London purchased this painting, Madonna of the Pinks, for œ22 million from the Duke of Northumberland. In 1968 the New York dealer Ira Spanierman purchased a dirty, unknown Italian-school painting at a Sotheby's auction for $325; soon afterward, scholars identified the work as the lost 1518 Portrait of Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino, by Raphael. In 2007 Spanierman sold the portrait at Christie's London for œ18.5 million ($37.3 million).

Grassi has made another important rediscovery of his own. In 2001 he purchased a "Circle of Pontormo" at an auction in Lyon, France, for $45,000. Again through an analysis of the painting's preparatory drawing, scholars quickly acknowledged the painting to be an original Pontormo--a fragment of the "lost" original for one of the most copied images in the Renaissance, with more than 25 known versions. When the work failed to sell at a Sotheby's auction in 2003, Yale curator Lawrence Kantor arranged for the painting to be purchased by the Yale University Art Gallery for substantially less than its low estimate of $800,000.

"This picture is powers of 10 more famous than any other painting," says Kantor. "But Marco had a great deal of difficulty persuading the art-historical establishment this was not just another copy. You will find that in auction rooms people buy with their ears and not their eyes. One scholar expressed doubts, and everyone else fell into line. This was one of the classic cases. I asked Marco permission, if the painting was bought in, if he would offer it to us. Being the gentleman he is, he did, and we were able to buy it at a very reasonable price."

Museums are now bringing the subject of art restoration to prominence with special exhibitions. This past fall the Uffizi hosted an exhibition around the 10-year restoration of Raphael's Madonna of the Goldfinch. Through Sept. 6, Kantor's Yale Art Gallery is mounting an exhibition called Time Will Tell: Ethics and Choices in Conservation, about the history of restoration in its own collection, put together by Yale's chief conservator, Ian McClure. Both of the shows reveal a profession with a troubled history, according to Grassi. During the 1960s the Yale Art Gallery, operating under a hard-line theory in vogue at the time that called for removing all retouching and overpainting, badly stripped already-damaged work. Grassi describes that enterprise as "an absolute nadir in the annals of conservation." Kantor agrees: "Yale has one of the most dreadful histories of conservation in the known universe."

A generation later the recent Uffizi restoration of the Raphael aimed for a compromise between the traditional invisible style of restoration and the former Yale approach. Here a process, developed in Florence, infills damaged areas of a painting with a technique called "chromatic section," using pointillist-like brushstrokes that are noticeable up close but appear to blend together at a distance. Grassi remains critical of the technique: "At a certain distance the whole thing vibrates in a foggy way. This restoration doesn't do a picture any service, and it's nonsense."

An American citizen born in Florence, with degrees from Princeton and the Uffizi, Grassi represents the fourth generation of a Roman family of art dealers and restorers. Along with David Bull and Nancy Krieg in New York and Simon Gillespie in London, he has become a central player in the private practice of Old Master conservation--one of those experts who work outside the conservation departments of major museums. He pursues a traditional method of restoration, believing that results should bow to the original and be invisible rather than becoming the subject of discussion. "The best intervention is the one less seen," he says, quoting the Bergamo nobleman Giovanni Secco Suardo, who published a handbook on the restorer's art in 1876. Dressed in bespoke tweeds, Grassi works in a studio overlooking Broadway and Houston Street in New York's SoHo District. His career in restoration has taken him through Florence, Lugano and, in the mid-1960s, the Villa Favorita in Castagnola, Switzerland, home of one of Europe's greatest private collections, that of Baron Heinrich von Thyssen-Bornemisza. In the mid-'70s Grassi relocated to New York, and in 1984 he opened his current studio office, where he has served a clientele of dealers, private collections and auction houses.

Today Grassi Studio handles a select number of these clients while attending to work for Grassi's son Matteo, who runs an Old Masters gallery in Paris. The office is a hospital for old art, one that sees its share of masterpieces mixed in with more common examples. "There is a democracy in a conservation studio," says Grassi. "It's a ward in a hospital. All paintings have the same appendix. And sometimes the hardest problems are on mundane paintings." He limits himself to older work. "I would not do contemporary painting. There's a very big divide that occurs around the Second World War. Paintings by Picasso and Mir¢, technically, were not made differently from the past. The big change came with Pollock. The materials changed radically--cotton canvases, acrylics, different materials with totally different chemical and physical properties. Having come from a Florentine background, I have worked on 13th-century painting. In Rome I worked on the earliest panel painting in the West. For me, the earlier the better."

Grassi Studio is lined with wooden freight boxes used to protect paintings in transit. At the center of the main lab is the large low-suction vacuum table, the emergency-room tool that adds elasticity and tension to brittle and dry canvas through a slow application of heat, humidity and pressure. "The traditional process was to reline the canvas," Grassi says, explaining the utility of the device. "But this allows you to take an original canvas and treat it so it doesn't need lining. It gives it added life." Around the room are paintings currently under Grassi's care, some on gurneys, others making the rounds from X-ray room to infrared-video station to the workstation containing scalpels, solvents and binocular microscopes. Despite the gadgetry, restoration is "a craft, in the end," says Grassi. "You are working with your hands. You have to know the chemical properties of paintings and test them. You need good light and good lighting equipment. And the most important tool is the eye. That's what really counts."

Research into a painting's provenance and an informed sense of connoisseurship are also vitally important. Although his studio is now half the size it was when it was in full operation (Grassi is winding down in anticipation of his retirement), he still retains an 18,000-volume art library, one of the largest such resources in the city. He keeps it in a wood-paneled study next door to the bright restoration rooms. "For years I did nothing but scour book catalogues--a huge investment. It was vanity, too. In fact, people used to joke that for the cost of the library I could have a car idling out front to take me to the Frick," Grassi says, referring to the art reference library at the Frick Collection, on Manhattan's Upper East Side. "But having the information is very, very valuable. And having it sooner than the next guy is more valuable."

It is this expertise that causes Grassi to be sought out by private collectors like the one who bought the Holbein. Soon after the Drouot auction, Grassi realized that no known Holbein portrait of Erasmus--or even any of the copies--featured the subject in quite the same pose, holding a closed book. The new owner sent the painting to Grassi in New York, and once he had it in the studio, he was able to analyze it under a special kind of infrared camera. Infrared reflectography can reveal features below the painted surface that are invisible under normal light. Scanning the portrait, the camera showed extensive preparatory drawing and redrawing in the area of the hands and book. Grassi describes the discovery as "the first truly heart-stopping moments of revelation."

An X-ray radiograph showed further reworking--ear flaps had been added to Erasmus' cap. "These findings pointed in one obvious direction," says Grassi. "It was highly unlikely that the portrait could be a copy. Not only was an exact prototype unknown, but copyists invariably follow the model line by line without improvisation." Other characteristics reaffirmed the authenticity of the piece. The wood of the panel was European linden, what one might expect of a painting made in Switzerland or Southern Germany, as opposed to the oak used in England and the Low Countries or the poplar one finds in Italian panel painting. The studio sent the sample to the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Forest Sciences Lab for testing. "They do it for no fee," says Grassi. "It's fantastic. It's one of those nice things for which you pay your taxes." At the same time, he investigated the provenance of the portrait, as far back as possible, and was able to trace its ownership to a prominent French family of the ancien r‚gime, the Lamoignon, who had connections to Holbein.

The evidence was adding up. The attribution came to focus on Holbein himself. What remained was the quality of the work. It might not have been a copy, but was the portrait good enough to have been painted by the master's hand, was it a product of Holbein's studio or a combination of the two? Once Grassi removed the older varnish, which is a routine procedure, "the exceptional quality and delicacy8 of the modeling, the meticulous detailing and the lustrous finish all spoke clearly to the great diligence and proficiency of its creator," he says, "whoever he might have been."

But still there was something off about it. Grassi asked the late Swiss conservator Emil Bosshard, a colleague and friend from the Villa Favorita, to examine the painting. He in turn arranged for an examination by the art historian Pascal Griener, a Holbein expert. Together they began to question the dark green background of the portrait, which contrasted with the delicacy of the figure. "The background is important because the figure has to resonate with it," Grassi says. Bosshard submitted some small pigment cross-sections to Hermann Kuhn in Munich, formerly of the Doerner Institut, for testing. The resulting microphotographs confirmed what the experts had suspected. The background, originally a light green, had been painted over more roughly in a darker shade. Since this was done early in the life of the painting, the overpaint came to form a tight bond with the original layer. This discovery posed a dilemma for the conservator. Grassi discussed its potential removal with Bosshard, who thought a cleaning procedure would pose too many difficulties and dangers to the painting.

When the painting returned to New York, Grassi ran several more tests of the overpaint layer. Finally, he devised a solvent solution that was able to soften the overpaint without damage to the material beneath. Working over the surface of the painting in tiny quadrants with the solvent, a binocular microscope and a scalpel, he was able to remove the overpaint during a period of several months. Grassi's efforts revealed the portrait in its full brilliance, for the first time in 400 years.

The decade-long restoration of this Holbein speaks to the challenges posed by a major rediscovery. The process does not happen overnight. When other rediscoveries get rolled out in the popular press as done deals, conservators such as Grassi remain skeptical. "The manner of the rediscovery is interesting. To come out and say, `I found this new painting' is like, `I found a cure for cancer.' It doesn't last long." Grassi points to the recently announced discovery of a purported Shakespeare portrait, purportedly painted from life, by the English restorer Alec Cobbe. Many critics now believe the painting was over-cleaned by Cobbe, and Tarnya Cooper, 16th-century curator at the National Portrait Gallery in London, has claimed that the work more likely represents the courtier Sir Thomas Overbury.

Careful restoration work can take years. The study and acceptance of a rediscovery by experts usually takes even longer. In the case of the Holbein, the chance scheduling of the Rotterdam show accelerated the process of acceptance. The canonization of this painting is not complete, however. More research needs to be done on Holbein's studio, in the way that scholars now understand Rembrandt's studio, notes Van der Coelen.

Yet the life of a restorer is not all rediscovered Holbeins and Pontormos. "There are certain things that give you satisfaction," says Grassi. "It can be a nondescript painting. The challenge is to resolve a problem, a structural problem, an aesthetic problem, and arrive at a solution that is acceptable aesthetically and artistically. It's great to work on a tremendous painting, but our daily life is made up of other things that can be equally satisfying."