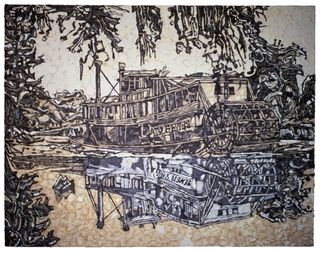

An opening at the Morrison Gallery, Kent, Conn.

ART & ANTIQUES

June 2010

Head for the Hills

by James Panero

Long known for antiques, Litchfield county, conn., has developed a serious contemporary art scene.

One of the best-kept secrets of the New York art world isn’t a neighborhood of converted lofts or gritty garrets. It’s a stretch of Connecticut countryside 90 miles north of the city called Litchfield County. “It’s very countryish, but much more sophisticated,” says Nicholas Thorn, vice president of Litchfield County Auctions. “It’s New England.” In 2008 Jane Eckert moved her gallery, Eckert Fine Art, from Naples, Fla., to Kent, an unassuming village at the center of Litchfield County’s growing contemporary scene. “To have as many galleries as we do in this area is unique,” she says. “They are just really first-rate, high-quality galleries.”

Occupying the northwest corner of Connecticut and incorporated back in 1751, Litchfield County takes its name from the even older Litchfield township (founded 1721), at one time the county seat. Two hundred years ago, Litchfield was one of the largest commercial towns in the state. America’s first law school was founded here in 1773 (its first graduate was Aaron Burr). In the early 19th century, the Presbyterian minister Lyman Beecher arrived to preach the gospel of temperance. His daughter Harriet Beecher Stowe was born in Litchfield in 1811.

Like much of New England, the area’s commercial fortunes declined in the late 19th century, but industry’s loss proved to be tourism’s gain. Opting out of the crowded beaches and hectic scene of other weekend destinations, successive waves of New York gentry gravitated to the preserved historical character and charm of the Litchfield Hills. In 1965, the private antiques dealer Peter Tillou became one of them. Tillou helped turn the historical hamlet of Litchfield into a center for American and English antiques. Peter’s son Jeffrey now runs one of America’s finest antique shops, Jeffrey Tillou Antiques, off the Litchfield village green and anchors the town’s antiquing district.

In the 1980s, a different scene took shape in nearby Kent. The furrier Jacques Kaplan, best known as the creator of “fun fur” and an eccentric collector of contemporary art, bought a second home in the area. In 1984, out of an old caboose parked on a rail spur in town, he founded a contemporary gallery that he called the “Paris-New York-Kent-Gallery.” Kaplan, who died in 2008, supported the opening of other Kent galleries and the arts of the area. “Jacques started it all. He put Kent on the map,” says Rob Ober, the owner of Kent’s Ober Gallery, founded in 2006. Now Kaplan’s efforts have been taken up by another transplant, James Preston, the former CEO of Avon. Along with his son, Matthew, Preston has been developing a 12-building complex of stores and gallery space, called Kent Village Barns, at the main intersection of town. “What Jim Preston did in these spaces, it added this modern spark,”says William Morrison, the owner of a soaring 7,000-square foot gallery at the center of the complex.

Kaplan’s promotion and Preston’s development have given rise to a host of sophisticated galleries within walking distance of each other and the other shops of Kent (the hot chocolate at Kent’s Belgique Patisserie is not to be missed). Morrison recently had a show of Hans Hofmann, and regularly shows monumental work by the painter Wolf Kahn and sculpture by Peter Woytuk, an area artist with a growing international reputation. Ober has shown Russian avant-garde art from the 1920s and satisfies his hunger for contemporary Russian work by inviting Russian artists to work in New York for a season and showing the results in his gallery. Both gallerists’ exhibition programs match artists who live and work in the area, like Allen Blagden, Tom Goldenberg and Sally Pettus, with established artists’ estates and up-and- comers from the city.

Many of the county’s small towns now boast their own art destinations. A gallery crawl (or drive, or bike) can extend to venues like The White Gallery and Argazzi Art in Lakeville, New Arts in Litchfield, Joie de Livres in Salisbury, KMR Arts and Behnke Doherty Gallery in Washington, and Ella’s Limited and Traces Fine Art in Bantam. Several of the area’s artists have open studios along the way. The painter Curtis Hanson operates what is perhaps the best known. His studio, in a converted church called Cornubia Hall tucked in the valley of Cornwall Hollow, is one of the most picturesque sites in the region.

Weekend antiquing is one thing, but the area’s thriving arts scene has been supported by a singularly sophisticated demographic that calls Litchfield home, or at least second home. “When I look through the top 200 collectors in the world, there’s here,” says Morrison. “Aggie Gund comes in. Jasper’s been in here.” Johns, that is, who lives in a large estate up the road in the town of Sharon.

“You’ve got some of the biggest collectors here,” says Ober. Ray Learsy and Melva Bucksbaum, whom Ober calls “the Medicis of Litchfield County,” live in Sharon. “They are huge supporters of the arts,” says Ober, “and their taste is eclectic.” The husband-and- wife collecting team have just completed a state-of-the-art private museum and storage center on their property called the Granary. Their invite-only vernissage in mid-December was complicated only by an ice storm that descended on the county and kept several of the guests away. The unaccommodating weather served as a reminder that while its art scene may be international, Litchfield County remains true New England—and no one would want it any other way.