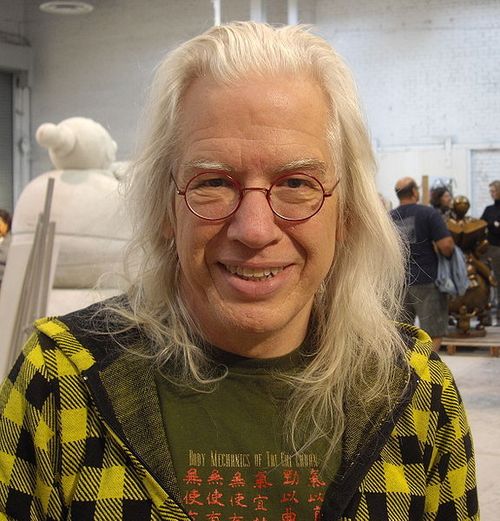

Installation shot from “Matthew Miller: the magic black of an open barn door on a really sunny summer day, when you just cannot see into it,” courtesy of Famous Accountants.

THE NEW CRITERION

June 2011

Gallery Chronicle

by James Panero

On “Matthew Miller: the magic black of an open barn door on a really sunny summer day, when you just cannot see into it” at Famous Accountants, Queens; “Don Voisine” at McKenzie Fine Art; “Stephen Westfall: Seraphim: Paintings and Works on Paper” at Lennon Weinberg; “Jules Olitski: Embracing Circles 1959–1964” at FreedmanArt, New York; “Jacob Collins: New Work” at Adelson Galleries; and “Exhibition of Contemporary American Realism” at the National Arts Club, New York.

The summer doldrums are not what they used to be, in art as in everything else. New York now barely takes a break before the September push. Still, it seems the galleries often save the best for late spring. It’s a vestige of an old cycle, one that wanted big just before the un-air-conditioned city ran for the water in the dog days of summer. It’s no different this year, with many shows now to see, little time to do it, and (in my case) about 1,800 words left to review them. So here goes.

In life, dark is the absence of light. In painting, black has a presence all its own. Black can be a force, both a profundity and a tangible thing holding court on the canvas. The title of Matthew Miller’s current solo show is “the magic black of an open barn door on a really sunny summer day, when you just cannot see into it.”[1] When you have 1,750 words left in your review, that’s quite a title. But this show’s name, taken from the artist’s notebook, helps illuminate the spectacular blacks that mark this young artist’s iconic work.

Born to a Mennonite family in Pennsylvania, Miller draws on the primitive portraiture of his region, where he encountered the work of itinerant Amish painters. As a star student at the New York Academy, a proving ground for realist painters, Miller channeled this influence through his own native talent. Here he developed a signature style of portraiture that places his subjects in a field of jet black. This black functions as its own enveloping shape as well as a dark void contrasting with his blindingly bright figures.

Miller sometimes depicts other people in his portrait program, but he has become his own best subject. I wouldn’t call his self-portraiture a vanity project. It’s more like an unsparing self-examination. In successive paintings laid down in numerous layers of glaze, Miller tugs, presses, mashes, and pulls at his own physiognomy. The results are haunting, psychological illustrations—Neue Sachlichkeit by way of Pennsylvania Dutch.

The Famous Accountants gallery has assembled five of these self-portraits in its narrow space, each called Untitled, ranging in date from 2008 through 2011. Carved out of the basement of a tenement brownstone by the artists Ellen Letcher and Kevin Regan, FA (as it’s known) has proved to be the most innovative art space in Bushwick, Brooklyn, while actually existing just over the borough border in Ridgewood, Queens. The gallery specializes in obsessive, chilling, high-wire installations—one artist (Andrew Ohanesian) recently re-assembled an actual airport jetway in the space; another (Meg Hitchcock) wrote the Book of Revelation on the wall using letters individually cut out and re-pasted from a Koran. In Miller’s case, the eyes of his portraits come alive and black performs its particular magic in this must-see exhibition.

Black is the muscle in Don Voisine’s abstract work. In his show at McKenzie Fine Art, each painting follows a similar program: on two opposite edges, a thick band and narrow vein of color; in the middle, a black and white design.[2] By removing his hand from these hard-edged oils on wood, Voisine lets the shapes define themselves. The simplicity of his designs gives them their force. Voisine is a precisionist, an abstract technician who uses the textures of matte and glossy paint to signal shifting volumes, and planes stacked one on top of the other. In all of the designs, the edge colors compress the compositions while the black pushes out. In Pan (2011), a small horizontal work, the blacks seems to bend around an edge, thanks to shifting textures and subtle changes to the angle of edges. Volume (2010) similarly looks like a cube in sideways view. In Otto (2010), the black is pneumatic and ready to pop. In all of these works, blacks bump, stretch, and twist with tense energy, subjects in themselves.

Stephen Westfall is a patternist who always seems to unlock the dazzle in repetition. A few years ago in these pages, I called My Beautiful Laundrette (2008), his work I saw in a group show at Lohin Geduld Gallery, “my new favorite painting.” It’s still up there, but Westfall’s latest exhibition at Lennon Weinberg might give it some competition.[3] “Seraphim: Paintings and Works on Paper” is the result of Westfall’s year as a fellow at the American Academy in Rome. Clearly the stay was worth it. Westfall says he drew particular inspiration from the tenth- and eleventh-century floors of Cosmatesque churches. The paintings that result have dispensed with some of the subtle brushwork and idiosyncratic pattern placement of his earlier designs in favor of bold patterns on a grand scale.

Wise One (2011) is built from four squares of diagonal bands of color arranged in a diamond. Westfall’s particular knack for variation comes into play in its color program. One can see connections oscillating among all of the color bands, but just as patterns emerge—a spiral here, a mirror there—Westfall mixes it up. Subiaco (2010), with its greens and yellows and reds, seems lifted right off the tiles of a Roman wall. Westfall balances this design so well that x-shapes, crosses, diamonds, and squares all emerge from the same arrangement, as though different frames on a flickering screen. Then there is Ariel (2011), the largest work in the show, and one that turns out to be latex painted right on the gallery wall. I’m not the first to suggest a comparison here to Sol LeWitt, but considered against the dull, flat work of that conceptualist, Westfall leaves nothing to chance. His lively paintings are the products of a master craftsman.

In an age of gallery closings, it’s nice to welcome an opening, especially when the opener is the inimitable Ann Freedman, the former director of Knoedler and Company. Freedman-Art is her new venture with several familiar names. The artists Frank Stella and Lee Bontecou have joined her, along with the dealer Per Jensen, also of Knoedler. The fact that she situated her new gallery right above the best cappuccino shop in New York, at Madison and Seventy-third Street, could be viewed as another masterstroke.

FreedmanArt’s inaugural show brings out rarely seen work from the estate of Jules Olitski, the other thoroughbred in her stable.[4] Olitski is having a moment right now, with a major survey at the Kemper Museum underway, curated by E. A. Carmean, Alison de Lima Greene, and our own Karen Wilkin (Houston, Toledo, and Washington are up next on the tour).

FreedmanArt’s exhibition focuses on the period from 1959–64. Much to his credit, Olitski never developed a signature style. Instead, he consistently tested the limits of paint, which pushed him to innovate with new techniques and materials—sometimes towards indecent compositional ends. In the early 1960s, he stained some large canvases with acrylic, laying down intense color combinations in biomorphic shapes. Known as his “core” paintings, ten of these works are now on view at FreedmanArt. The colors resonate against each other. Medusa Pleasure (1962) is the simplest, with one blue circle vibrating in a field of red, a color that fills the eye. Most of the others have two circles glancing off each other, as though in cellular division. It’s appropriate that all these shapes have an embryonic form, because this work gave birth to the artist’s next creations. If anything can be said against them, it’s their relative comportment. These paintings only hint at the mad experiments to come.

Jacob Collins is significant not only as an artist but also as an educator. This teacher is at the leading edge of a movement to revive the artisanal crafts of traditional painting. Born in 1964, he has already trained a generation of painters, who now teach their own disciples, through his off-the-grid schools and ateliers (most recently, his own Grand Central Academy).

Collins is still at work on his own self-education. Now at Adelson, the blue-clip gallery a block from the Metropolitan Museum, where he set about studying the Old Masters two decades ago, we can find his recent portraiture, still lifes, and landscapes mixed in with half-finished graphite studies on paper.[5]

A revealing self-portrait in pencil at the gallery entrance shows the intensity of an artist in middle age—thin, slightly hunched over, haggard, with wire-like hair, puffy eyes, and the shine of a furrowed brow caught in white chalk. Collins is at his best drawing the surface of the face and the knots of the skin. This mastery is the result of an intense regimen that first focuses on sketching plaster casts. His finest paintings occur when he can transfer these drawings to canvas. So his nudes, lifted from life drawings, are often his most successful and arresting works, almost shocking in the intimacy of their finely rendered flesh.

Even here, however, Collins’s observational techniques do not always move flawlessly to canvas. As he builds up his light areas with paint, his darks are left thin, often receding into the warp and weft of the linen. The left hand of the stunning Reclining Nude Morning (2011), although dangling over some bright sheets, seems to sink below the surface of the surrounding pigment, especially around the fingers. Seated Nude Dusk (2011) is more problematic, as a face in shadow becomes almost illegible, burned out against the bright light of the arms and legs. I get the feeling that Collins is aware of these issues of contrast. Across some work, he can be seen experimenting with his treatment of light, working up identical landscapes at different times of day.

Much of the best work to come out of the realist camp, with heavy representation by Collins and his former students, was on view for a brief two-week stay last month at the National Arts Club in New York.[6] In a survey of highlights, I thought that two by the young Joshua LaRock, a Collins protege, were showstoppers. The exhibition was presented by a new organization called the America China Oil Painting Artists League (acopal). The alliance hints at the geopolitics that may prove to be a game changer for this school of American traditionalists. The Chinese inherited their Old-Master techniques from the Soviets, who used realism as a tool for propaganda. Unlike Beaux Arts in the West, in the East traditional training and the taste for realism never fell out of favor. That’s why most contemporary Chinese artists, including those exported to the West, paint so effortlessly in a realist mode. It also explains why the rise of China might shift the balance of artistic taste in the global market, with outsider American realists recast as central players. If this comes to pass, Collins might well be considered their mentor—and, as a painter, still a first among equals.

[1] “Matthew Miller: the magic black of an open barn door on a really sunny summer day, when you just cannot see into it” opened at Famous Accountants, Queens, on April 30 and remains on view through June 5, 2011.

[2] “Don Voisine” opened at McKenzie Fine Art, New York, on May 5 and remains on view though June 11, 2011.

[3] “Stephen Westfall: Seraphim: Paintings and Works on Paper” opened at Lennon Weinberg, New York, on April 26 and remains on view through June 11, 2011.

[4] “Jules Olitski: Embracing Circles 1959–1964” opened at FreedmanArt, New York, on May 13 and remains on view through Summer 2011.

[5] “Jacob Collins: New Work” opened at Adelson Galleries, New York, on May 11 and remains on view through July 28, 2011.

[6] “Exhibition of Contemporary American Realism” was on view at the National Arts Club, New York, from May 17 through May 26, 2011.