THE NEW CRITERION

February 2012

Gallery Chronicle

by James Panero

On “MIC:CHECK (occupy)” at Sideshow gallery, Brooklyn; “Gabriele Evertz: Rapture” at Minus Space, Brooklyn; “Lori Ellison” at McKenzie Fine Art, New York & “Halsey Hathaway and Gary Petersen: New Paintings” and “Paintings by Rob de Oude” at Storefront Bushwick, Brooklyn.

I am not the first to suggest that Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, the study of price bubbles and other mass misconceptions written by the Scottish journalist Charles Mackay in 1841, has something to say about present circumstances. Men “think in herds,” wrote Mackay. “It will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one.”

Before the downturn of 2008, Damien Hirst appeared to ride the wave of irrational exuberance. Here was the artist of the mad herds. In 2007, he fabricated a diamond-encrusted skull, which he called For the Love of God, and made headlines attempting to sell it for 100 million dollars. Then months before the crash, he unloaded his stock for top dollar at Sotheby’s. Just in time, it seemed, he cashed out in an art world example of the “greater fool theory,” with sorry speculators left holding the bag of his worthless

gewgaws.

For anyone who thought Hirst popped louder than a Vegas exurb after that auction, the past month has been a reminder that there’s still air left in the pneumatic Brit. The dealer Larry Gagosian has scheduled an exhibition of Hirst’s “spot” paintings in all eleven of his galleries spread across eight cities on three continents, with a total of 331 works on display worldwide. Regarding these canvases of colored dots painted by Hirst’s studio assistants, the finest comment has come out of a viral video by the internet personality Hennessy Youngman, who called them a “perfect storm of banality.”

Unlike many of our other toxic assets, Hirst somehow avoided the downgrade of 2008. He has positioned himself as a bubble about a bubble, madness about madness, as much of a statement on popular delusion as a product of it. He designs his artwork to appear valueless—blown-up baubles, useless pills, the trinkets of a carnival midway writ large—then sits back as his prices plump up against all reason. What matters is the way we respond to them. Amplified through a feedback loop of supposed meaning, popular reaction builds into a deafening noise that Hirst and his supporters point to as evidence of his ability to resonate with mass hysteria.

Brilliant, right? Except for one thing: I always thought Hirst was worthless, and I’ve yet to meet anyone who thought otherwise. So where is the madness? It doesn’t exist. It never did. The Hirst bubble was never the product of mass delusion. It was something far less interesting—a fake bubble puffed up and maintained by a syndicate of gallerists, museum professors, PR flacks, art gossip reporters, and moneyed collectors. The only madness surrounding Hirst is the hype they generate for him and our exasperation at the inanity of the spectacle.

And, of course, we always knew that. As the critic Will Brand recently wrote: “I’m going to lay this down, just to clarify, so that nobody from the future gets confused: We hate this shit. Everyone hates this shit. These spots reflect nothing about how we live, see, or think, they’re just some weird meme for the impossibly rich that nobody knows how to stop.”

The Gagosian shows are merely groundwork for Hirst’s retrospective at Tate Modern this spring. The Tate will then promote future sales at Gagosian. And so on. That’s the insidious thing about the Hirst bubble. Unlike a real bubble, we never want to buy in, yet somehow we end up holding the goods anyway, in this case through our public institutions. We did not willingly inflate anything. Instead, the Hirst bubble blows up by knocking the air out of the rest of us. It comes down to a battle over air rights. So many artists are making vital work today. They could resonate the spots off Hirst. They just need their air back.

Sideshow Gallery, Williamsburg, Brooklyn (installation view)

Art abhors a vacuum. It needs atmosphere to bounce its energy around. That’s why artists, writers, and videographers are slowly building their own infrastructure to support an alternative ecosystem for serious art. They are finding ways to nurture the art they value most. And little would be possible without alternative galleries to exhibit this work. I have written many times in this space about the galleries in Bushwick, Brooklyn. Yet before Bushwick was even on the map, there was Sideshow Gallery, founded in 1999 by Richard Timperio in the nearby neighborhood of Williamsburg.

For the past twelve years, Timperio has hosted a regular group exhibition at Sideshow that has become a main event in alternative art. Timperio reclaims some air from the establishment’s machine with a spectacle of his own. His group show is a demonstration of the power and the numbers of the art scene gathering across the East River on New York’s Left Bank of Brooklyn—the rising Montparnasse. For this year’s show, on view through February 26, he has gathered over four hundred artists to exhibit their work across every square inch, floor to ceiling, of his gallery’s two-room home.1

The artists here are tied together in more ways than one. This is not some museum curator’s idea of what’s hip this season but rather an organic network that has long been showing and working together, in some cases for over half a century. These artists do not exhibit here expecting to sell. They give their work over to Sideshow to demonstrate their affinity with the alternative scene. On opening night, the line goes around the block, even without advertising or coverage in the mainstream media.

I have never seen a larger gathering of work by great contemporary artists, with many I have previously covered in this column, including Lori Ellison, Tom Evans, Gabriele Evertz, Bruce Gagnier, Dana Gordon, Ronnie Landfield, Loren Munk, Carolanna Parlato, Peter Reginato, Paul Resika, Lars Swan, Kim Uchiyama, Don Voisine, Louisa Waber, John Walker, and Thornton Willis. Then there are artists whom I know better in their other roles—as the critic Mario Naves, the gallery owner Janet Kurnatowski (who, a few blocks away, is now exhibiting her own annual exhibition of works on paper), and Lauren Bakoian, the director of Lori Bookstein Fine Arts.

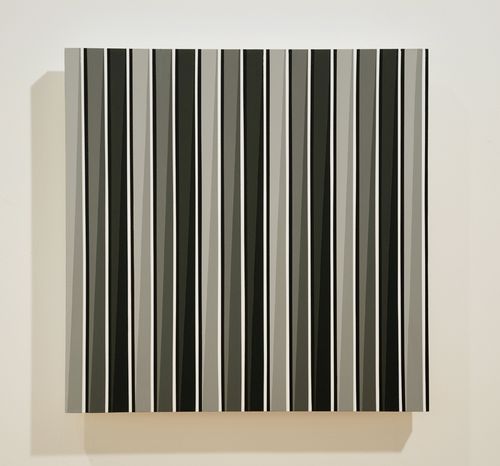

Gabriele Evertz, Six Grays + B/W (2002, acrylic on wood, 16"x16")

With its crowded bodies and crowded walls, Sideshow offers a must-see exhibition that is a challenge to view. It is an annual conference of alternative art as well as a card catalogue of artists to follow throughout the year. Of particular note this year is the small panel by Evertz, an example of this colorist’s investigation into gray that was the subject of a breathtaking show at Minus Space.2 Landfield’s small canvas reveals the lyrical abstractionist at his finest. Uchiyama’s watercolor on paper was a spare standout. Gordon is a Sideshow regular whose Orphic investigations into shape and color have led him to create some of the best paintings of his career. More of his work will be on display this month at the Triangle Arts Association in a group exhibition called “What Only Paint Can Do,” curated by our own Karen Wilkin.

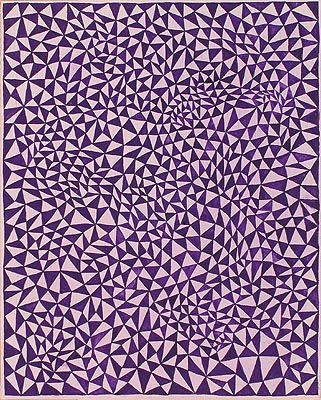

Lori Ellison, Untitled (2011, Gouache on wood panel, 10 X 8 inches)

Through exhibiting at Sideshow and Valentine Gallery in Ridgewood, Queens, Lori Ellison is one artist who has used both social media and the alternative galleries to land, after many years, in the catbird seat of public acclaim. For decades she has made wondrous, intimate drawings and panel paintings from the sidelines. Now she is enjoying a solo show at the superb Chelsea gallery McKenzie Fine Art that is a tribute to her dedication and a testament to the emerging dynamics of a new and more open contemporary scene.3

McKenzie has matched Ellison’s recent geometric and biomorphic pen drawings and gouaches on wood with a series of arabesques from a decade ago, some painted in glitter glue. The comparison is interesting. While remaining idiosyncratic, Ellison has clearly distilled out the cuteness over the years, refining her geometry and color sense to create the crackling abstractions we see today. While her works are nothing if not obsessive, they have evolved in a way that speaks to the seriousness of her studio practice and explains how she now comes to have our undivided attention.

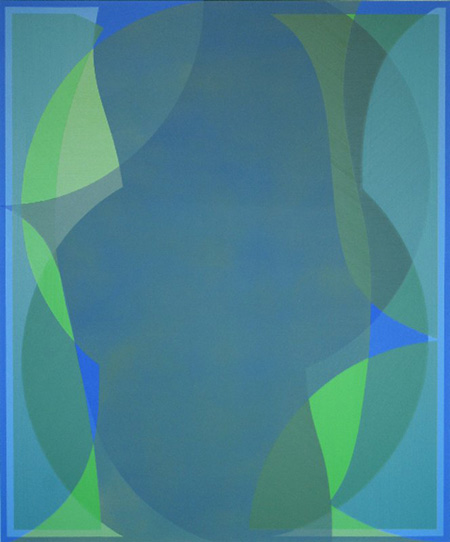

Halsey Hathaway, Better Me Than You (2011, 60" X 50" acrylic)

Meanwhile in Bushwick, the Sideshow artist Gary Petersen has found a home at Storefront Bushwick. This is the new gallery opened by Deborah Brown housed in the same location as the groundbreaking space she co-founded with Jason Andrew two years ago—simply called Storefront. As a curator, Brown is a matchmaker, drawing on an extensive network to pair artists across generations. Her first show is a visual stunner, with Petersen’s hard-edged dynamos of swirling stripes matched with Halsey Hathaway’s overlapping disks and, in the back room, Dutch-born Rob de Oude’s moiré patterns of meticulously painted lines.4

Lee Bontecou, Sandpit (2011; mixed media; 24 x 19 inches)

Finally this month offers up our last chance to see the art world’s original alternative in her current show. Lee Bontecou always refused to be taken in. After bursting onto the scene in the 1960s with her singular and haunting wall sculptures of layered canvases, often stitched around gaping voids, she retreated entirely from public view. Yet she never stopped making art. Now in her eighties, she is as inventive and singular as ever. Her exhibition of drawings and sculptures on view at FreedmanArt through February 11 is not to be missed.5

While Bontecou has always been reluctant to explain her work, for her retrospective in 2003 she briefly relented. “The natural world and its visual wonders and horrors,” she explained, “man-made devices with their mind-boggling engineering feats and destructive abominations, elusive human nature and its multiple ramifications from the sublime to unbelievable abhorrences—to me are all one.”

Bontecou works at the intersection of man, nature, and machine. Her neo-Gothic, steampunk, post-apocalyptic aesthetic owes something to her upbringing: her father invented the first aluminum canoe; her mother wired submarine transmitters. But even here she resists easy labeling, seeking to occupy “all freedom in every sense.” At FreedmanArt, creations are more undersea than overhead, with delicate ocean crafts suspended from the ceiling and odd plant- and mollusk-like creatures peering up from sandbox dioramas, all paired with drawings of waves, flowers, and eyes.

When Donald Judd wrote that Bontecou can reference “something as social as war to something as private as sex, making one an aspect of the other,” he hit on only two of her many readings. Dore Ashton offered an elaboration. “Far more significant than the obvious sexual connotations so often invoked for her work,” she observed, are the mysterious and ultimately “inexpressible sources of her imagery.”

1 “MIC:CHECK (occupy)” opened at Sideshow gallery, Brooklyn, on January 7 and remains on view through February 26, 2012.

2 “Gabriele Evertz: Rapture” was on view at Minus Space, Brooklyn, from November 5 through December 17, 2011

3 “Lori Ellison” opened at McKenzie Fine Art, New York, on January 5 and remains on view through February 11, 2012.

4 “Halsey Hathaway and Gary Petersen: New Paintings” and “Paintings by Rob de Oude” opened at Storefront Bushwick, Brooklyn, on January 1 and remains on view through February 5, 2012.

5 “Lee Bontecou: Recent Work: Sculpture and Drawing” opened at FreedmanArt, New York, on October 27, 2011 and remains on view through February 11, 2012.