THE NEW CRITERION

May 2016

Gallery Chronicle

by James Panero

On “Amy Lincoln” at Morgan Lehman Gallery; “Paul Resika: Recent Paintings” at Lori Bookstein Fine Art; “Rob de Oude: Tilts & Pinwheels” at DM Contemporary; and “Thornton Willis: Step Up” at Elizabeth Harris Gallery.

The challenge facing a realist painter is often not how to portray the visible world but rather how to visualize the unseen. Like the separation of man from beast, the pursuit of the ineffable separates art from illustration. To get from one to the other requires a leap of faith, and, for much of art history, that faith was Faith. In modern times, the fracturing of religious consensus has not so much dampened realism’s spiritual interest, as might be expected, but rather placed artists in an even more central role as both shamans and craftsmen. In making manifest their own sense of the unseen, they advance their own spiritual programs.

There can be little doubt that bunk and questionable faith, from Theosophy to Mammonism, have often informed modern art’s spiritual expression. At the same time, it must be said that bearing witness—even (perhaps especially) false witness—has led to much of modern art’s visual charisma.

An interest in animism, or a belief in the spiritual animation of animal, vegetable, and mineral, has produced some of modernism’s most arresting visual expressions of the natural world. In the first half of the last century, the American artist Charles Burchfield, for example, looked to reproduce not just woods and fields but also “the feelings of woods and fields, memories of seasonal impressions.” Painting nature with redolent waves and golden halos surrounding bushes and trees, Burchfield wrote, “I like to think of myself—as an artist

—as being in a nondescript swamp, up to my knees in mire, painting the vital beauty I see there, in my own way, not caring a damn about tradition, or anyone’s opinion.”

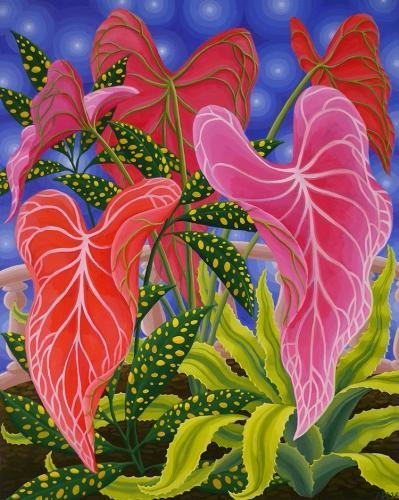

The painter Amy Lincoln follows in Burchfield’s muddy footsteps, looking not only to plant life but also to what might be considered the inner life of plants. Drawing on the obsessive horticultural precisionism of Henri Rousseau, Lincoln incorporates an outsider-artist sensibility for symmetry, overgrowth, and oversaturated color. Now at Morgan Lehman Gallery in Chelsea, she is showing a selection of her smaller acrylics on panel, all created in the last year.1

Lincoln has been focusing on the life of plants since I first began seeing her work in the off-grid galleries of Bushwick several years ago. Over time these still lifes have become more active, energized by increasingly surreal colors, ominous forms, and ever stranger settings. Following a residency last year at Wave Hill, the stunning horticultural estate overlooking the Hudson River in the Bronx, and one with consistently excellent artist programs, Lincoln has incorporated a wider variety of plants in her paintings along with architectural details from the garden grounds. Greenhouse windows, Hudson River ice floes, and the cliffs of the Palisades have all appeared in recent work.

At Morgan Lehman, the beaux-arts balustrade of Wave Hill’s terraced gardens peeks out from behind several of her compositions and unites the work together. This selection may be Lincoln’s most uncharted and otherworldly. Sun, moon, and stars illuminate bloodleaf, caladium, taro, and rubber plants with unnatural light. Colors shift in radiating waves and give her leafy shapes, rendered up close, an ominous presence.

At times the hyperreality can become cartoonish. Her stars in Caladium Study (2016) would have been better left as single sources of light rather than rendered as five-pointers. The same goes for her sun waves in Veranda Study, which seem drawn from a box of

Kellogg’s.

Yet aside from its overdone lunar craters, the most unsettling and successful work in the exhibition is Spring Moonlight, a mountain landscape of pink-purple light and daffodils. Here the strangeness is so overdone, so saturated, that the image verges on kitsch. Yet like a velvet painting of Elvis, the composition also fully inhabits a world of its own idols and idolatry. Whether we should believe in it, or whether Lincoln even believes in it, is an open question, and one we should enjoy trying to answer.

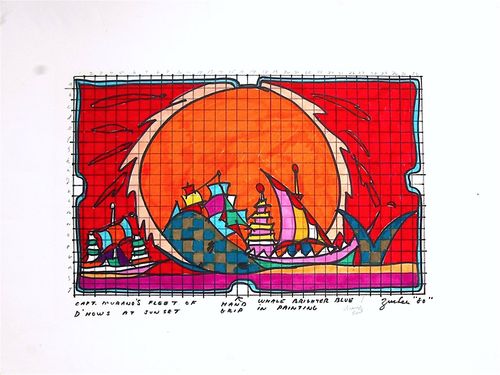

For eight decades Paul Resika has painted with a timeless immediacy by working in dialogue with an academy of Masters, from Old to Modern. Hans Hofmann, Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese, Canaletto, Puvis de Chavannes, Camille Corot, Gustave Moreau, Georges Rouault, Claude Monet, and Théodore Rousseau, to name a few, all appear to be frequent collaborators. Resika looks to them as uninterrupted sources to connect with his brush, drawing seemingly disparate artists and time periods together.

Now on view at Lori Bookstein, his eighth solo show at the gallery, Resika is exhibiting a series of paintings mostly based on a single theme, a still life of pitchers and shells, processed in different modes through his pantheon of influences.2

I saw a selection of these paintings in advance of this exhibition on a visit to Resika’s Upper West Side studio, a space where the Ashcan School used to meet, and through which Resika draws his own connections. Ranging from realistic to impressionistic to abstract to points in between, the series is a concise statement of Resika’s broad reverence for the artistic past. Through its uncanny variety of styles painted with equal, unironic affection, the series could not be the work of any other artist.

What ties it all together is a sense of touch. The Venetians did not need to sign their own paintings, since their brushstrokes served as their signatures. Resika similarly has developed his own way of handling paint. Like the haze of the Venetian lagoon, he imbues his work with an atmosphere of color-filled strokes.

Resika’s body of work has never been an easy fit in the history of modern art. Yet he attributes his nonconformist sensibility to his modernist mentor, Hans Hofmann, who unexpectedly laid the groundwork for his classical and renaissance explorations.

After finding early artistic success in New York, his hometown, Resika traveled first to Venice in his twenties to live with the Tintorettos in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, and later to Vaucluse to walk in the footsteps of Corot.Such wanderings may at one time have been considered insufficiently forward-thinking, uncommitted to the mandates of the present moment. But Resika’s stylistic freedom now seems ahead of its time—that of a modernist painter who joyfully refuses to break with the past.

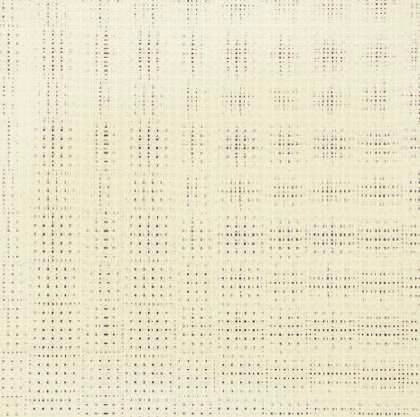

From Salomon van Ruysdael to Piet Mondrian, the Dutch have always had a particular feel for the line. On view last month at DM Contemporary, the Amsterdam-educated, Bushwick-based painter Rob de Oude brought a Dutch sensibility to New Amsterdam in a solo show of his square oils, all featuring straight colored lines.3

Would it be too much to attribute this exhibition titled “Tilts and Pinwheels” to the influence of the horizon line of the Lowlands, intersected by masts, steeples, and windmills? Perhaps that would be tilting at windmills. What is clear is that de Oude uses grids and intersections to produce remarkable optical effects—moiré patterns of uncontrolled waves that somehow radiate out of his ruled precision.

De Oude is following in a tradition of optical painting that goes back more than a century. Yet like other contemporary painters reevaluating this visual terrain, de Oude looks for more than just optical dazzle, towards paintings with personal feeling and mood. At DM Contemporary, his earlier work on display showed an interest in collapsing systems. In Puncture Pattern (2014) and Keep On Keeping On (2015), an abundance of threaded lines build from a screen into a thicket.

More recently, de Oude has turned those inward forces around. Always a colorist, he now employs complex color gradations to explode his forms into shimmering constellations—works that are at their best when they retain some mass, such as in Grid Shift (2016) and Forward in Reverse (2016). Ever more accomplished as a visual technician, de Oude will now need to keep his compositions grounded as they look increasingly up.

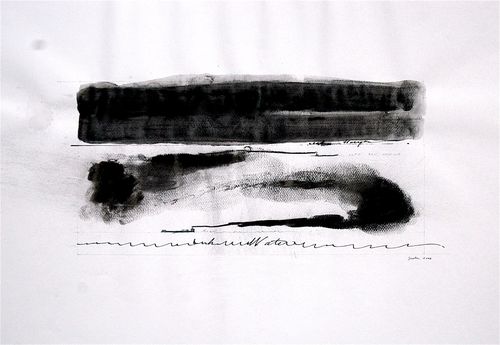

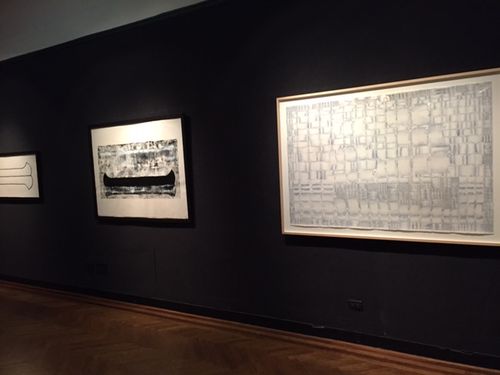

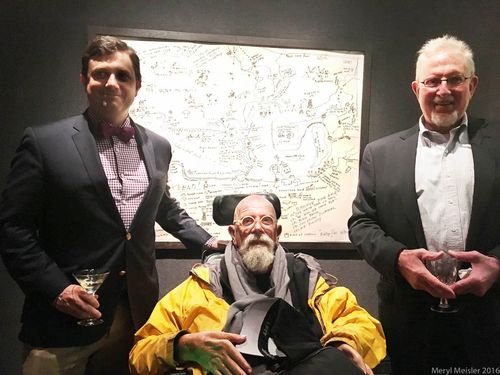

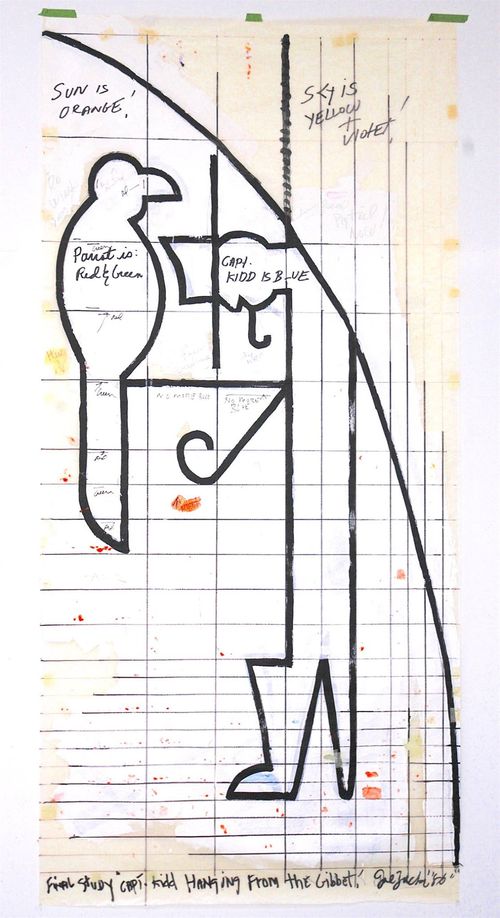

Thornton Willis, the painter’s painter, returns to Elizabeth Harris Gallery for “Step Up,” his latest exhibition of new work.4

An original Soho abstractionist, and an artist whose work has appeared often in this column, Willis has grown ever more energized and primal since coming of age in the downtown painting scene nearly half a century ago. Willis’s compositions can appear simple, especially in reproduction, but such simplicity supports Willis’s sophistication in his handling of color, edge, and line. Whether push and pull, or figure and ground, Willis looks to place his compositions on point, ultimately leaving the viewer in the balance. In the current exhibition, Willis continues with a motif from his last two shows by layering step-like blocks and stairways. In Stairway to the Stars (2015) and Lockstep (2015), the pieces of his compositional puzzles rest in their own notches. In another series here, his most recent, colorful squares and rectangles teeter on edge.Step Around (2015) and Spin Step (2016) work through a push-pull dynamic that is not so much in and out but up and down, with the precarious block stacks fighting against the pull of gravity.

A third series, and my favorite, revisits Willis’s lattice constructions, but here as vertical stripes called “totems.” These simplest of shapes, slightly variable in length, read as both windows and obstructions, barriers to entry and power chords of energy, balanced in Willis’s uniquely confident way.

Timed to this show is a new hard-bound collection, Interviews & Essays, about Willis’s life, featuring critical writing by Julie Karabenick, Vittorio Colaizzi, and Lance Esplund. I am pleased to be included in this selection as well. The time has come for this painter whose work has taught me much about abstraction to receive wider attention and appreciation.

1 “Amy Lincoln” opened at Morgan Lehman Gallery, New York, on March 31 and remains on view through May 7, 2016.

2 “Paul Resika: Recent Paintings” opened at Lori Bookstein Fine Art, New York, on April 28 and remains on view through June 4, 2016.

3 “Rob de Oude: Tilts & Pinwheels” was on view at DM Contemporary, New York, from March 11 through April 23, 2016.

4 “Thornton Willis: Step Up” opened at Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York, on March 31 and remains on view through May 7, 2016.