WALL STREET JOURNAL, April 27, 2017

New York History Goes Into Hiding

After the New-York Historical Society’s latest renovation, informed by a mixture of ideological and commercial concerns, there are far fewer objects on display.

"Objects tell stories” is the message that flashes across the video monitors of the new permanent-collection galleries of the New-York Historical Society. The phrase might serve as a mantra for what the museum and library is describing as the “transformation” and “reimagined installation” of its fourth floor, which opens to the public this Saturday, April 29, after a $35 million overhaul.

Less discussed, however, is what has been transformed: A museum once defined by its singular holdings and their mode of display has now turned its collection into a sizzle reel of teachable moments.

For starters, tens of thousands of objects that had been on permanent view—treasures that have defined and described local history—have been taken down, with many of them shipped offsite to storage in New Jersey.

But there’s more: The society has chosen to destroy its fourth-floor display of “visible storage”—the unmediated assembly of its trove of objects—which had made a majority of its collection of 70,000 objects publicly available. Known as the Henry Luce III Center for the Study of American Culture, this award-winning, floor-wide installation, completed in 2000, was a place to become lost in the rich material of New York’s history. All this has been reduced to a single gallery, with only a fraction of the collection left on view.

The old Luce Center was a “sentence with a lot of nouns and no verbs,” Louise Mirrer, president and CEO, noted on a recent tour. In its place, the society has chosen curatorial interpretation through immersive and interactive technologies. Or as Ms. Mirrer, who has overseen many prior successes at the society, puts it, the new installation is designed “to dazzle our multiple and varied audiences” with the stories behind the objects.

And so, as the 4,800-square-foot centerpiece of the floor, the museum’s encyclopedic collection of 100 Tiffany lamps has been set in a new “dramatically lit jewel-like space.” The multilevel gallery has been curated by Margaret K. Hofer, the museum’s director, along with Rebecca Klassen, the assistant curator of material culture, and designed by the Czech architect Eva Jiřičná. Its curving cases and glass staircase—inspired by Ms. Jiricná’s work for the Victoria and Albert Museum and for high-end retail—make visiting the museum more like browsing a Mac store. The space includes a “hands-on ‘Design-a-Lamp’ experience,” where visitors can design a virtual Dragonfly shade and see the results on an illuminated model.

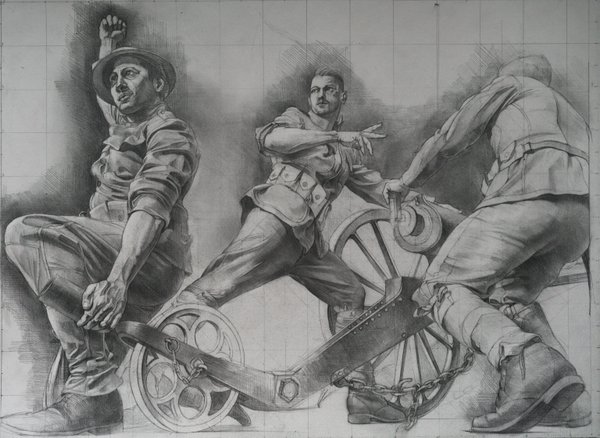

Despite the changes, the fourth floor retains the Luce name. It divides a small selection of objects from the permanent collection into 15 “themed niches” on topics ranging from infrastructure to slavery. Also included are 10 historical artifacts “that chart key moments in history,” all supplemented by interactive media. These range from the Civil War draft wheel that sparked the New York riots of 1863 to a graffiti-covered door from the 1970s.

The most radical—and political—transformation, however, is the new Center for Women’s History. “A lot of history is male-centric history,” explained Valerie Paley, the director of the center and the society’s chief historian, on another tour. “Infusing any narrative of the past with race, class and gender is important.”

This mandate now colors the entire floor. The new Tiffany gallery, for example, focuses on the “hidden history” of Clara Driscoll and her design team of “Tiffany Girls.” There is a section dedicated to tennis pioneer Billie Jean King. The new Joyce B. Cowin Women’s History Gallery hosts rotating exhibitions starting with “Saving Washington,” which focuses on Dolley Madison and the women of the early republic, with an immersive space featuring digital tables and life-size cutout photographs of historical re-enactors.

Meanwhile, an interactive video wall called “Women’s Voices” broadcasts at the entrance. These nine 50-inch touchscreens draw connections between Seneca Falls, the meeting of the landmark women’s rights convention of 1848, and such figures as Madonna and the “Women of SNL.”

“So many of our objects in our Luce Center looked like one big attic,” says Ms. Paley of the old installation. “We needed a narrative.”

But “attic” was the point. A truly radical approach to museum presentation, visible storage emerged in the 1970s as an effort to open museum collections to a broader public. The idea was championed by Henry Luce III, the heir to the Time Inc. fortune who, before his death at age 80 in 2005, had funded similar centers at the Metropolitan and Brooklyn museums, and the Smithsonian.

Its destruction here represents a signal event in museum culture. Since the 19th century, museums have been dedicated to preserving and presenting the objects of our cultural patrimony. Visual storage represents the apogee of this object-oriented approach. In its place we now have tutorials that “will challenge conventional wisdom,” in Ms. Mirrer’s words, “and inspire in us new thought and action.”

By contemporary standards, the new installation may be considered a great success—hectoring and seducing at once, with technologies that have the power to engage the public as never before. But such engagement, informed by a mixture of ideological and commercial concerns, also leads museums away from the primacy of art and artifacts. The society’s new floor certainly has a lot to say. It also has far fewer nouns through which to speak.