THE NEW CRITERION, February 2024

On “Bellini and Giorgione in the House of Taddeo Contarini” at Frick Madison, New York.

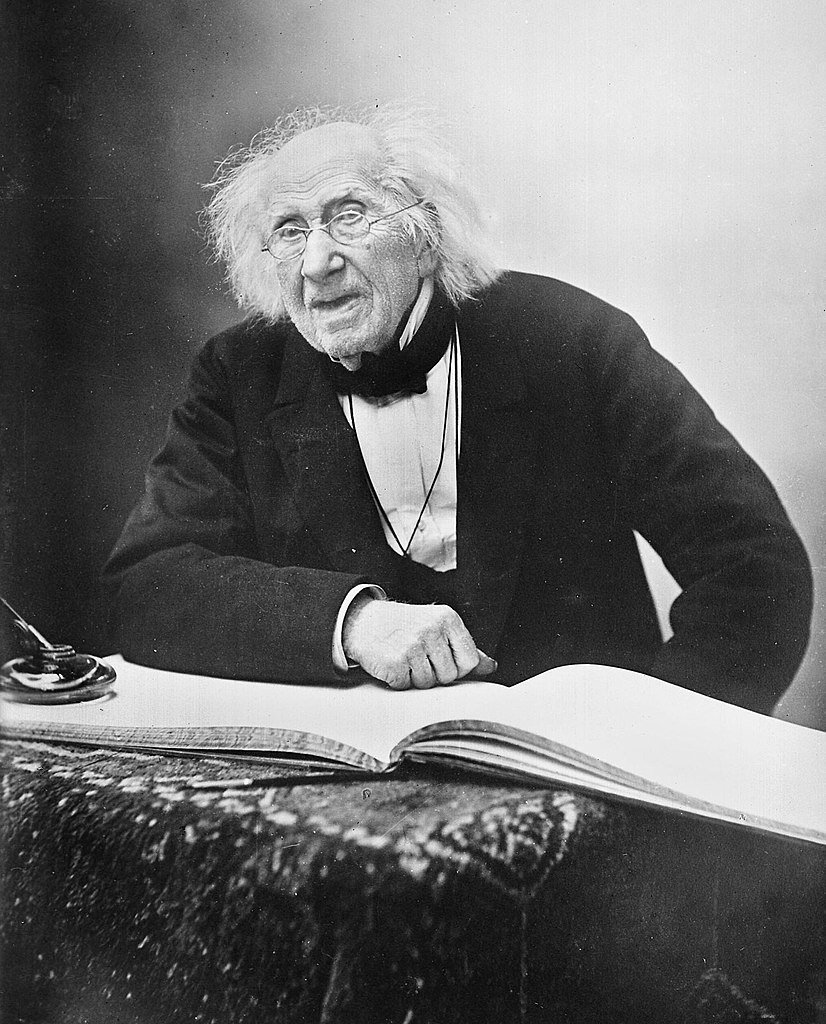

The arrival of a single painting in the United States is not often cause for a special exhibition. When the visitor, however, is a work by Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco, better known as Giorgione (ca. 1477–1510), you make an exception. Only about ten paintings are attributed today to the enigmatic Venetian, and The Three Philosophers (ca. 1508–09), now on loan in New York for the first time from the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, is among his greatest achievements. So the appearance of this canvas at the Frick Collection’s temporary home of Frick Madison is cause for a very special exhibition indeed. That this painting has been reunited—for the first time in some four hundred years—with its pendant composition, Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert (ca. 1475–80), the masterpiece from the Frick’s own collection that in the sixteenth century occupied the same Venetian palazzo as the Giorgione, is also cause for jubilation. This reunion is the occasion for a revelatory one-room show, “Bellini and Giorgione in the House of Taddeo Contarini.”1

The loan is the result of a pursuit that bordered on obsession for Xavier F. Salomon, the Frick’s Deputy Director and Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator. The exhibition is also a tribute to the Frick’s outgoing director, Ian Wardropper, who has set his retirement for next year, and his high-minded use of the collection’s temporary digs on Madison Avenue—the former home of the Whitney Museum, onetime outpost of the Metropolitan Museum, and future headquarters of Sotheby’s auction house. On March 3, the Frick will vacate these galleries that have functioned like private viewing rooms for its collection and move back to its mansion at One East Seventieth Street.

Installation view of “Bellini and Giorgione in the House of Taddeo Contarini.” Photo: Joseph Coscia Jr.

The installation of the Frick’s permanent collection on Madison Avenue—and in particular the presentation of St. Francis—was the inspiration for Salomon’s dream of reuniting the Bellini with the Giorgione. To underscore the worthiness of the unprecedented loan, in the accompanying catalogue published by D Giles Limited, Salomon collects everything we could possibly imagine about the creation, meaning, and provenance of The Three Philosophers and its relationship with St. Francis in the Desert.

Three years ago, I wrote about the effect of seeing St. Francis in the Desert in the light of Frick Madison (see “Sublet with Bellini” in The New Criterion of April 2021). A raking illumination fills the scene from beyond the left frame—unseen by us, but fully apparent to Francis, who exposes the symbolic wounds of the stigmata on his hands and feet. Flora and fauna fill this vision of his rocky hermitage as the rays seemingly melt its icelike outcropping into a stream, watering a kingfisher below. Kenneth Clark noted how “no other great painting, perhaps, contains such a quantity of natural details observed and rendered with incredible patience: for no other painter has been able to give to such an accumulation the unity which is only achieved by love.”

Giorgione, The Three Philosophers, ca. 1508–09, Oil on canvas, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Photo: KMH-Museumsverband.

At Frick Madison, positioned in its own alcove, the painting has been lit by one of Marcel Breuer’s trapezoidal windows in a way that accentuates the work’s own luminous dynamics. Light and shadow, depiction and reality glow together. The Three Philosophers has now been hung on this alcove’s opposite wall, which had been left empty before the arrival of the Giorgione. Again we are presented with figures in a rocky landscape, this time three men in colorful robes, with two standing and one seated. The similarities in these compositions of roughly equal size are striking, especially as the two paintings can now be observed together. The hills in the distance share uncanny form, as do the designs of the distant towns with their arched construction. The stepped stones in the foregrounds seem like mirror formations. Even the tiny pebbles appear to have been quarried from the same source.

The two paintings interact the more you move around them and take them in. Are we looking at the same scene depicting two different periods of time? Or are these two sides of the same outcropping, with the stone floor of Frick Madison now running between them? While the direct lighting of St. Francis leaves little doubt of its divine origin, the illumination of the Giorgione is more elusive. A sun low on the horizon seems to be setting, but the figures appear to be lit with an unexplained glow. Those “three philosophers” may be seen carrying scientific instruments and tablets relating to the sun and moon, but the lighting of the composition is non-Euclidian and otherworldly. It is almost as if the radiance of the Bellini is now bouncing off of the Giorgione in mystical, lunar-like reflection.

Giovanni Bellini, St. Francis in the Desert, ca. 1475–80, Oil on panel, Frick Collection, New York. Photo: Michael Bodycomb.

As is often the case with Giorgione, the more we look into this young painter’s work, the less we understand it. Anyone who has tracked down Giorgione’s small painting The Tempest (ca. 1508) in Venice’s Gallerie dell’Accademia can likewise attest to the mystery of that strange and tender scene of a nursing mother, an idle man, and ruined architecture beneath a stormy sky. Who are they? Where are we? What are we seeing? The questions strike like a thunderclap emanating from the clouds above. Here is something more than just visual storytelling with known characters and stock symbols. Rather it is something absorptive, mysterious, and new.

The same goes for The Three Philosophers. The composition has warmed observers with its brilliance but also baffled scholars about its meaning since just about the time of its own creation. In 1525 a Venetian collector by the name of Marcantonio Michiel (1484–1552) was making a survey of art in the Veneto when he recorded a definitive account of these paintings together in what he titled his Pittori e pitture in diversi luoghi (Painters and paintings in different places). This manuscript was later published as his Notizia d’opere di disegno (Information on works of design).

In his account of the paintings “in the house of Messer Taddeo Contarini,” written in the Venetian dialect, Michiel lists ten works. One of them is “three philosophers,” he writes, a “canvas in oil of the three philosophers in the landscape, two standing and one seated who is contemplating the sun’s rays, with that stone finished so marvelously . . . begun by Giorgio from Castelfranco and finished by Sebastiano Veneziano.” Another is a “Panel of St. Francis in the Desert,” which Marcantonio Michiel identifies as an oil by “Zuan Bellini, begun by him for Messer Zuan Michiel, and it has a landscape nearby wonderfully finished and refined.”

Installation view of “Bellini and Giorgione in the House of Taddeo Contarini.” Photo: Joseph Coscia Jr.

Marcantonio Michiel’s account is significant for several reasons: for coining the titles of the two works (3 phylosophi and S. Francesco nel diserto); for its clear descriptions of the paintings (dui ritti et uno sentado che contempla gli raggii solari cum quel saxo finto cusi mirabilmente and un paese propinquo finito et ricercato mirabilmente); for information about their authorship and provenance (Fu cominciata da Zorzo da Castel Franco, et finita da Sebastiano Venitiano and Fu opera de Zuan bellino, cominciata da lui a Ms. Zuan michiel); and for describing them together in one private collection (In casa de Ms. Tadio Contarino).

Recorded some forty-five years after the creation of St. Francis, seventeen years after Three Philosophers, fifteen years after Giorgione’s death, and nine years after the death of Giovanni Bellini (ca. 1424/35–1516), Michiel’s survey is also revelatory for what it leaves out: the identity of those three philosophers, as well as the particular moment depicted in Saint Francis of Assisi’s life. Both have been sources of discussion and conjecture ever since. For St. Francis, most scholars now agree that the image depicts the saint’s stigmatization, not in the “desert” but rather at his Apennine retreat at La Verna. Still, two standard references are missing: the seraph delivering Christ’s wounds, and Brother Leo. An alternative interpretation is that we are rather presented with Francis composing his Canticle of the Creatures, that prayer to “Brother Sun, Sister Moon, Brother Wind, Sister Water, Brother Fire, Sister Mother Earth, and Sister Bodily Death.”

The Giorgione poses an even greater conundrum. “Apart from Giorgione’s Tempest,” writes Salomon in his exhibition catalogue, “very few Venetian Renaissance works have received as much attention and been as widely interpreted as The Three Philosophers.” The identification of those “three philosophers,” which was left unstated by Marcantonio Michiel even within two decades of its execution, has resulted in centuries of conjecture. Assuming the painting in fact depicts “three philosophers” from antiquity, the proposed combinations as collected by Salomon have included the following: Archimedes, Ptolemy, and Pythagoras; Aristotle, Averroes, and Virgil; Regiomontanus, Aristotle, and Ptolemy; Ptolemy, Al-Battani, and Copernicus; Aristotle, Averroes, and a humanist; and Plato, Aristotle, and Pythagoras. Alternatively, the figures might represent the Three Magi; or Marcus Aurelius studying with two philosophers on the Caelian Hill; or Abraham teaching astronomy to the Egyptians; or Evander and Pallas showing Aeneas the Capitoline Hill; or a meeting between Sultan Mehmet II and Patriarch Gennadios Scholarios in Constantinople; or Saint Luke, King David, and Saint Jerome; or King Solomon, King Hiram of Tyre, and the master craftsman Hiram of Tyre as they plan the Temple in Jerusalem; or perhaps even the painters Giovanni Bellini, Vittore Carpaccio, and Giorgione. For Xavier Salomon, the most convincing identification, as proposed by the scholar Karin Zeleny, is that of Pythagoras with his two teachers, Thales of Miletus and Pherecydes of Syros, “the first three philosophers of the Western tradition shown while at the Oracle of Apollo at Didyma.” I am more partial to the poetic approach proposed by the art historian Tom Nichols in his book Giorgione’s Ambiguity, in which he suggests that our interpretation is meant to remain free-floating and open-ended. Deliberate ambiguities, he writes, are Giorgione’s “visual traps set to capture the viewer’s curiosity and speculation.”

“Uncertain about authorship, patronage, dating, and the significance of both paintings,” writes Salomon, “when it comes to Giorgione’s Three Philosophers and Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert, we know much less than we think we do.” What is certain is that these paintings occupied the same Venetian home soon after their creation, even if the specific location of Taddeo Contarini’s residence in the neighborhood of Cannaregio has been up for debate. Marcantonio Michiel writes that Bellini painted his St. Francis for Zuan Michiel, and the painting was then acquired by Taddeo Contarini (ca. 1466–1540) soon thereafter. It is possible that Giorgione’s Three Philosophers was a direct commission by this powerful and supposedly unscrupulous Venetian merchant—one even intended to complement the Bellini. While he may or may not have painted it for Contarini’s collection specifically, Giorgione most likely studied with Bellini, and so St. Francis might still have been front and center in his mind.

The last time these paintings were seen in one place was between 1556 and 1636. Like a flash of light of some divine rapture, their being brought together in this spectacular exhibition makes their connections manifest once again.