THE NEW CRITERION, December 2023

On “Vertigo of Color: Matisse, Derain, and the Origins of Fauvism” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

I beg the reader never to forget when it is asserted of the phenomena of simultaneous contrast, that one color placed beside another receives such a modification from it that this manner of speaking does not mean that the two colors, or rather the two material objects that present them to us, have a mutual action, either physical or chemical; it is really only applied to the modification that takes place before us when we perceive the simultaneous impression of these two colors.

—Michel Eugène Chevreul, The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors (1839, translated by Charles Martel in 1854)

The accentuation of color has been one of modern art’s defining preoccuptations. Now, as we process life through illuminated screens, we might even say that amplified color has become a feature of modernity itself. The secret behind modern color’s dazzling power is contrast. From the pointillist painters to our pixelated monitors, complementary hues in close proximity can take a shimmering hold of the senses. Modern painters were among the first to explore these pyrotechnics by drawing on the innovations of nineteenth-century color theory.

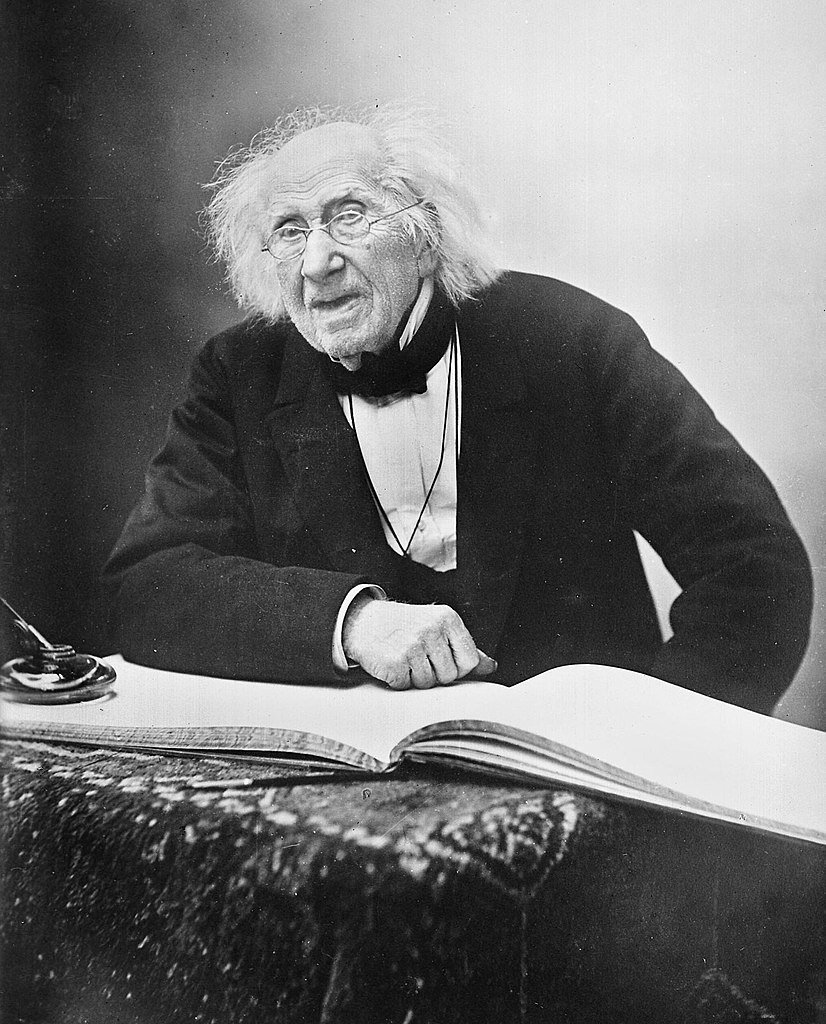

Michel Eugène Chevreul (1786–1889) was one such theorist who had a profound effect on art history. A groundbreaking chemist with a remarkable life and range of accomplishments, Chevreul did not set out to change the course of art when he wrote De la loi du contraste simultané des couleurs et de l’assortiment des objets colorés. Yet through his book on the effect of contrasting colors, which he published in 1839 and which was translated into English in 1854, Chevreul was among those who planted the seeds for what became the lush garden of modern art.

Michele Eugène Chevreul, nineteenth century. Photo: Unknown.

Born just before the French Revolution, Chevreul lived over a hundred years to see the construction of the Eiffel Tower, on which his name was inscribed along with seventy-one other scientists in France’s modern pantheon. The honor was well deserved: Chevreul’s research on animal and vegetable fats led to innovations in candle- and soap-making; he was the first to identify the excess glucose excreted by diabetics and the first to discover and isolate creatine in muscle; and through his studies of natural compounds, he became a founding father of organic chemistry.

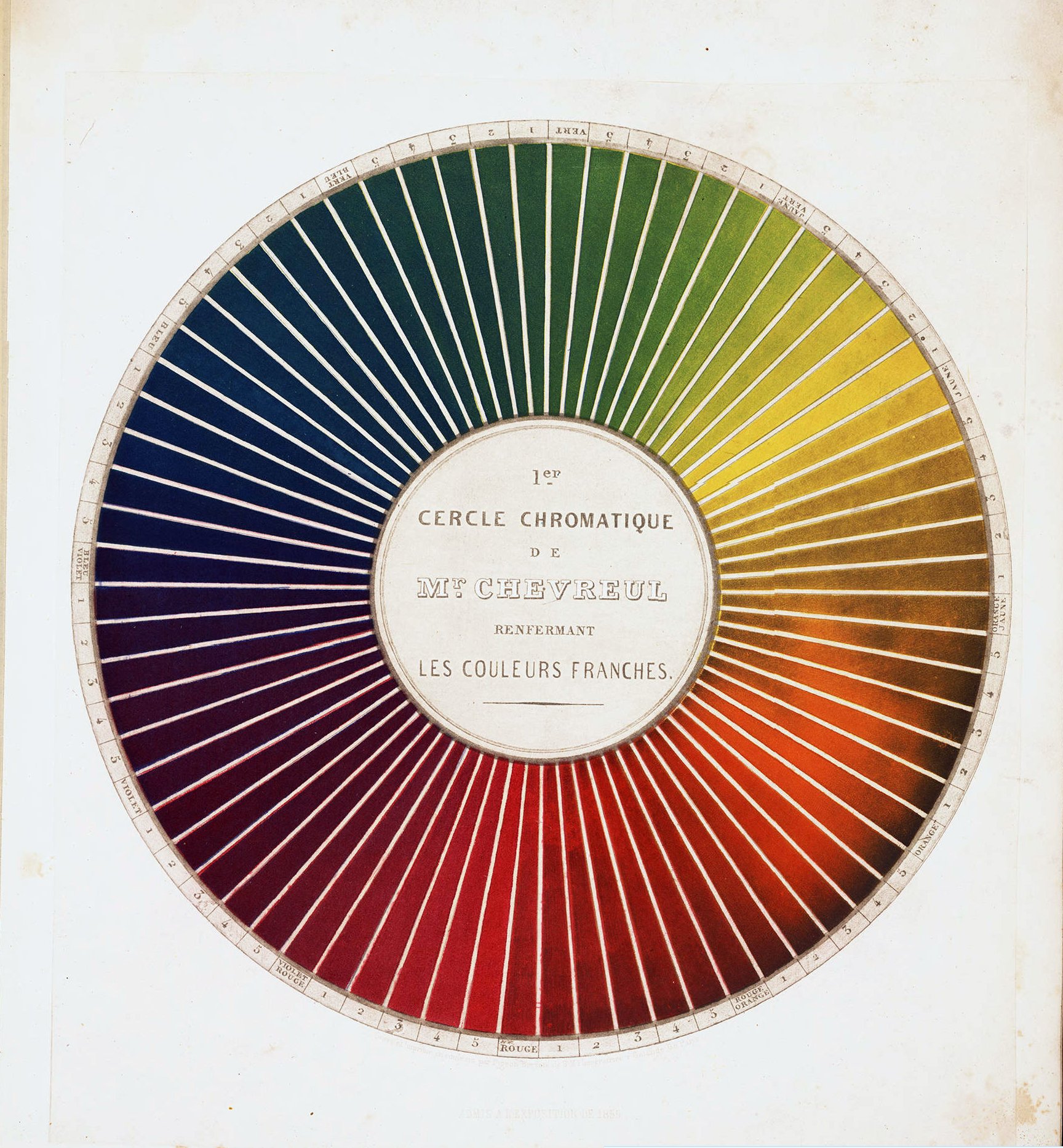

But it was an inadvertent discovery beyond the chemistry lab that influenced the future of art. In 1824, Chevreul became the director of the dye works at the Gobelins manufactory, the storied textile operation established in Paris in 1662 to supply tapestry for the royal court. An issue at the time of Chevreul’s arrival was the quality of its black thread, which was seen to shade into red under certain circumstances. By observing the black in isolation, Chevreul discerned that the effect was not a problem with the chemistry of the dye but rather with the proximity of the thread to other colors, in particular to blue. In other words, the effect was a matter of perception caused by optical interaction. In his subsequent book on this “harmony and contrast of colors,” which began as lectures at Gobelins, Chevreul expanded this research to reveal how certain hues appear dull when placed together, while others, in particular complementary colors from opposite ends of his color wheel, produce a sense of visual stimulation that exceeds the effects of the colors in isolation.

Through his study of contrasts, Chevreul found that while the mixing of complementary pigments would dull their effects, their juxtaposition in close proximity appeared to intensify their natures. By making a science of such contrasts, Chevreul suggested that the brightest colors were best mixed not on the canvas but in the palette of the mind, through what he called a “simultaneous impression.” He wondered, “What happens when two adjacent hues are complementary, like green and red?” Through an unexpected optical effect, “by the law of contrast, the two colors, being complementary, mutually strengthen each other; the green renders the red redder, and the red renders the green greener.”

Michele Eugène Chevreul’s color wheel

By considering the effects of color combinations on the observer, Chevreul’s study helped shift the focus of perception from representation to sensation. In his Principles of Color of 1969, Faber Birren called Chevreul one of the greatest names in the history of color. This was particularly true with respect to Chevreul’s influence on the Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists: “The pointillist style of painting, in which small dots or swirls of color are used to effect visual mixtures, was more or less founded in theory by Chevreul.” Camille Pissarro likewise reported that Georges Seurat sought the “modern synthesis with scientifically based means which will be founded on the theory of colors discovered by M. Chevreul.” As Birren concluded:

The painting schools of Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism were devoted almost entirely to the combination of pure color, tint, white. . . . Previously, most artists had employed ochers, browns, somber shades of green, maroon, blue. The Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists glorified the phenomena of light and used spots of color in an attempt to achieve luminous visual mixtures.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the Neo-Impressionists had turned art into their own modern science, with set prescriptions of how they believed they could deploy contrasting pigments to maximum effect. Understanding the role of light in exposing such contrasts, many of these artists gravitated south, to work under the more direct summer sun. Here in the intense illumination of the Mediterranean, they found the light to explore and develop their ideas of color.

For Henri Matisse (1869–1954) and André Derain (1880–1954), a single such summer spent painting together in 1905, in the Mediterranean fishing village of Collioure, led to what we now know as Fauvism, the “beastly” next chapter of modern art’s exploration of color. “Vertigo of Color: Matisse, Derain, and the Origins of Fauvism,” an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, now gathers their paintings, studies, and correspondence from this remarkable stay.1

Of the two artists, Matisse was the older and more established. He had spent the previous summer of 1904 with Paul Signac and other Neo-Impressionists in Saint-Tropez. Luxe, Calme et Volupté, Matisse’s groundbreaking painting from that sojourn, now in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay, reflected Signac’s Divisionist principles of contrasting color while also revealing Matisse’s expressive style; “Vertigo of Color” includes a study for this work on loan from the Museum of Modern Art. As Matisse looked to continue these explorations, it was Signac, an accomplished mariner who first sailed to Collioure in 1887, who brought the remote village to the attention of Matisse and his family. “Contrasts and color relationships, here lies the secret to drawing and form,” Signac wrote as encouragement to Matisse, quoting Paul Cézanne.

Henri Matisse, Luxe, Calme et Volupté, 1904, Oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

For all that he owed to Signac, Matisse was ready to move beyond the color precepts of Neo-Impressionism, or what he called the “tyranny of Divisionism. One can’t live in a household that is too well kept, a house kept by country aunts.” In Collioure, a Catalan fishing village fifteen miles north of the Spanish border, he found the isolation necessary to push his palette and paint application in new ways. Years later, he remarked how “color for me is a force. My paintings consist of four or five colors which clash with one another expressively. When I apply green, that does not mean grass. When I apply blue, that does not mean sky. It is their accord or their opposition which opens in the viewer’s mind an illusory space.”

In this isolated stretch of France’s Vermilion Coast, which had only been accessible by sea before the tunneling of the railroad, Matisse did not end up working alone. In mid-June he received a letter from André Derain, an ambitious young painter over ten years his junior: “You know that I am quite alone in my ideas, which is very painful now. . . . Send me a postcard in which you beg me to join you instantly, recommending that I do this for my work.” Matisse did just that: “I cannot insist too strongly that a stay here is absolutely necessary for your work.” Three days later, on June 28, Derain wrote back: “I’ll soon be with you. I think this will make you as happy as it does me. I’m really glad, for a terrible bout of neurasthenia was beginning to shut me down.”

As assembled by Dita Amory, the Robert Lehman Curator in Charge of the Met’s Robert Lehman Collection, and Ann Dumas, Consulting Curator of European Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, “Vertigo of Color” brings together for the first time sixty-five of the paintings, drawings, and watercolors these two artists created while together in Collioure and the surrounding countryside —many of which have rarely before been on public view. “That legendary partnership, organized quite by chance, would forever change the course of French painting,” write the curators in the exhibition catalogue:

their daring color experiments ultimately challenged reliance on empirical evidence; their brushwork abandoned Neo-Impressionism’s strict adherence to formulaic divisionism; and their art evolved from sensory experience and from a raw and passionate dialogue in search of a new beginning.

In Collioure, Matisse made fifteen paintings, forty watercolors, and nearly a hundred drawings as preparation for larger work back in his studio. Derain, determined meanwhile to return to Paris with as many canvases as he could carry, composed thirty paintings on site that summer, along with twenty drawings and some fifty sketches. It is the concentration of this work assembled here that makes the exhibition so revealing. Arranged in the lower level of the Metropolitan’s Lehman wing, the show intermixes paintings and studies by the two artists in a looping progression that suggests their own sense of discovery, all while lending itself to the “vertigo” of color promised by the exhibition title.

André Derain, Fishing Boats, Collioure, 1905, Oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Raymond Paul, in memory of her brother, C. Michael Paul and Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, New York. © 2023 Artists Rights Society, New York / ADAGP Paris.

Both artists deployed dashes of bold, contrasting colors in their works, often leaving exposed light ground, but their palettes differed. Derain’s flaky surfaces of orange and blue appear baked in the Collioure sun. Matisse’s color choices—of lavender, peach, and green—are more sea-cooled. Matisse also comes off more at ease, as a painter willing to forego the illusion of depth for an intuitive sense of surface, while Derain holds onto the architecture of space, hammering away with his nails of color and light. Derain’s Fishing Boats, Collioure, from the Metropolitan’s collection, is a dense mosaic of orange, green, and blue. Meanwhile, Matisse’s Pier of Collioure, on loan from a private collection, is a windswept assembly of purple, pink, and teal.

André Derain, Henri Matisse, 1905, Oil on canvas, Tate, London. © 2023 Artists Rights Society, New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photo: Tate.

The portraits the artists painted of each other that summer, both on loan from the Tate, display their different color sensibilities while revealing the personalities of the other. Derain finds Matisse bearded and bespectacled, smoking from a pipe, his focused face rendered in orange and blue with a shadow cast in dense green. Matisse, meanwhile, captures Derain looking away, his thoughts elsewhere, in a loose application of light reds, greens, and blues.

André Derain, Woman with a Shawl, Madame Matisse in a Kimono, 1905, Oil on canvas, Private Collection, Courtesy of Nevill Keating Pictures, London. © 2023 Artists Rights Society, New York / ADAGP, Paris.

In addition to the port of Collioure, another subject the artists shared was Amélie Matisse. With her blue-and-white kimono, the painter’s wife sat for both artists, while also serving privately as a nude model for her husband. With its green background and red shadows, Derain’s Woman with a Shawl, Madame Matisse in a Kimono, from a private collection, is one of his most assured paintings in the exhibition. A year later, Matisse turned to the same composition himself, rendering Madame Matisse with Her Fan in pen and ink, in a work on loan from the Art Institute of Chicago. In Matisse and His Wife at Collioure, an ink on paper from the collection of the Met, Derain captured Henri painting a portrait of Amélie with an easel balanced on the rocky shoreline. The very portrait Matisse was composing that day, a study of colorful dashes and squiggles called La Japonaise: Woman Beside the Water, is also in this exhibition, on loan from the Museum of Modern Art.

Henri Matisse, La Japonaise: Woman beside the Water, 1905, Oil and graphite on canvas, Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2023 Artists Rights Society, New York / ADAGP, Paris.

At Collioure, each artist took color in its own direction. For Derain, “Colors became sticks of dynamite. They were primed to discharge light.” In a July 28 letter to Maurice de Vlaminck, his studio-mate back home, Derain wrote that “this color has messed me up. I’ve let myself go with color for color’s sake. I’ve lost all my old qualities.” Matisse, meanwhile, settled into ever greater assurance as a colorist. As he remarked years later:

I applied my color, it was the first color of my canvas. I added a second color, and then, instead of making a correction, when this second color did not seem to accord with the first, I applied a third to create such an accord. Then, I had to continue in this way until I sensed that I had created a complete harmony on my canvas, and that I had discharged the emotion which had made me undertake it.

We can see this complete harmony in Open Window, Collioure, a painting on loan from the National Gallery of Art and a supreme example of simultaneous contrast. Looking onto the boats in port from an open window, Matisse unites inside and out, the refraction of sun and shadows, not through the distinction of light and dark but through the interaction of purple, green, and pink. Taken together, the colors unify the surface of the picture while also capturing the sensation of blinding light through an overwhelming sense of color. Here in his intuitive application of contrast, Matisse most successfully departs from his Neo-Impressionist influences—reflecting what the critic Louis Vauxcelles (who coined the term Fauvism) had advised him earlier that year: “Your gifts are too magnificent, mixing and balancing intuitive sensations and will, for you to lose yourself in experiments that are sincere but that go against your true nature.”

Henri Matisse, Open Windown, Coullioure, 1905, Oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Collection of Mrs. John Hay Whitney. © 2023 Artists Rights Society, New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Both artists returned from Collioure just in time to cause a sensation with their work at the 1905 Salon d’Automne, an exhibition that cemented both of their careers. Matisse knew he had achieved something important that summer. As he wrote to Signac in September, “It was the first time in my life that I was content to be exhibiting, for my things are perhaps not very important, but they have the merit of expressing in a very pure way my sensations. Something I’ve been working toward since I began to paint.” When Leo Stein saw Woman with a Hat, now in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Art and not included in the current exhibition, he remarked it was a “thing brilliant and powerful, but the nastiest smear of paint I had ever seen.” The work served to introduce Matisse to Leo and Gertrude Stein, their brother Michael, and his wife Sarah. The Steins in turn introduced Matisse to the Cone sisters, the Baltimore collectors who soon bought several of his works and became lifelong patrons.

Despite his own lingering doubts, Derain experienced an equally impressive reception in Paris. The dealer Ambroise Vollard took up his cause and sold paintings from Collioure to the Russian collectors Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov. Vollard also commissioned Derain to paint fifty views of London, hoping to repeat the success of Claude Monet’s impressions of the Thames from a decade before. Derain was so critical of the London weather that he finished the works in his French studio. Nevertheless, by the summer of 1907, Vollard had purchased thirty of these compositions. Derain’s Palace of Westminster (1906–07), from the Met’s own collection, is included here along with Matisse’s Young Sailor ii (1906) and View of Collioure (1907), from the artist’s return to the village. These final works reveal the direction of both artists, and in particular Matisse, as they freed themselves to explore color without precondition—as Matisse said, “to reach that state of condensation of sensations which constitutes a picture.” All are a product of that summer of 1905. The collaboration of these two artists resulted in a simultaneous contrast that continues to shimmer.