From "State of the Art" on view at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art: Isabella Kirkland, Emergent, 2011. Oil and alkyd on polyester over panel. 60 x 48 in.

THE NEW CRITERION

October 2014

Gallery Chronicle

by James Panero

On “State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now” at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art; “Ellen Letcher: Gaslight” at Hansel and Gretel Picture Garden Pocket Utopia; “Amy Feldman: High Sign” at Blackston; “Katherine Taylor: New Sculptures” at Skoto Gallery; and “Robert Otto Epstein: Sleeveless” at 99¢ Plus Gallery.

Everyone knows there is more to contemporary American art than the Whitney Biennial. The Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, which opened in 2011 in Bentonville, Arkansas, wanted to find out for itself just how much more. Since 2013, the museum president Don Bacigalupi and the curator Chad Alligood logged 100,000 miles visiting nearly a thousand artists’ studios across the country. Their discoveries have now been brought together in “State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now,” the museum’s first of what I hope will be a recurring series of contemporary surveys, and the reason why my art season began with a flight to Fayetteville and a short taxi-ride to Bentonville.

As opposed to the slick knowingness of big-city surveys (largely populated by coastal artists and the curators’ friends and former students), the Crystal Bridges assembly is a diverse, heterogeneous, and creaky affair. In some cases, especially in the first exhibition room, the squeakiness is audible, as the mechanics below Lalu, a sculpture by the Knoxville-based John Douglas Powers, competes against the more sublime vision, above, of automatic reeds waving against a projected sky.

The entrance to "State of the Art": Andy DuCett, Mom Booth, 2013-14. Interactive installation. Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Rather than seek out the hollow and detached, the Crystal Bridges curators went for the uplifting and engaged—at times too uplifting and engaged—as no rhinestone was left unturned in an exhibition that embraces sentimentality and even tackiness (of the unironic kind). The best work here is the meticulous, the realistic, and the strong-willed—art that tends to get overlooked as overwrought and under-intellectualized. I was especially struck by the totemic juju sculptures of Vanessa L. German, the verdant nature scenes of Isabella Kirkland, and the Renaissance revivalism of Jamie Adams. The Brooklyn-based Meg Hitchcock, whose intricate collages of religious texts I featured in this space last season, represents the aspirations of Crystal Bridges at its best.

From "State of the Art": Vanessa L. German, White Naptha Soap or, Contemporary Lessons in Shapeshifting, 2013. Mixed media assemblage. 55 x 15 x 26 in. Courtesy and Photo: Pavel Zoubok Gallery, New York

It is impossible not to walk away from this survey without additional suggestions for the mix: I would like to have seen more of those painters who identify as classical realists, routinely balkanized from the contemporary discussion, as well as the military and civilian illustrators who document the recovery of wounded soldiers and sailors through the Joe Bonham Project. Nevertheless, with “State of the Art” Crystal Bridges has fulfilled a mission to serve as a bridge for the art of the United States, connecting the wide range of the two-million-odd artists working in what I might call America’s outer-outer borough scene.

Installation from Ellen Letcher: Hansel and Gretel Picture Garden Pocket Utopia

The artist Austin Thomas, whose Pocket Utopia was one of the first galleries in Bushwick before its relocation to the Lower East Side, has now made the unexpected jump to Chelsea, pairing with the gallery Hansel and Gretel Picture Garden. She has brought her stable of Bushwick artists with her, promising to deliver some genuinely advanced work to the edges of those blue-chip hedgerows. Her first Chelsea-based exhibition features Ellen Letcher, an artist of the Bushwick old guard, who until recently ran her own pioneering (and imaginatively titled) outer-borough gallery, Famous Accountants.

For years, Letcher’s day job in magazine production gave her easy access to her raw materials—fashion photographs—which she cut up and juxtaposed, pasting, layering, and moving them around on paper using paint as a binder. In her hands the images lost their slick gloss and revealed more sinister underpinnings. Her collages were, in part, inquiries into the image-making of her daylight profession, while also serving as commentaries on larger themes.

Now at Hansel and Gretel Picture Garden Pocket Utopia, Letcher explodes the tidy frames of her works on paper and occupies the space like one large collage. The exhibition riffs on the provisional and the transitional, with plastic wrap partially covering at least a couple of sculptures and a handful of paintings spilling out onto the floor. A drop cloth, once used in preparing her collages, forms the basis for one work. A chair covered with paint, and the paint splatterings scraped off the studio floor, form another. In one respect, the installation looks like the artist’s studio, where she has run out in a hurry. In another respect, the presentation brings the violence of her collage-work to the surface. Instead of merely clipping off the head of an image, Letcher decapitates the head of a statue suffocating in plastic, a head that now appears as an independent work for sale. Elsewhere, scratchy messages, such as “We Decided Not To Fight,” have been gathered together and pinned and taped to the wall, part personal sayings, part song lyrics.

The dark tone of this show can be seen as an allusion to world events, albeit a clairvoyant one, since the work came together before the atrocities of late summer. The exhibition opened on the same day, August 20, that ISIS released its snuff film of the journalist James Foley. If artists are the early warning systems of history, Letcher has deployed an advanced installation with ominous long-range sensitivities.

Installation from Amy Feldman: High Sign

Amy Feldman’s paintings are hard to miss. They convey a haunting stillness through a unique economy of means. Her work, in fact, may be the most hauntingly economical paintings around right now. Feldman uses just two tones, gray and white, in her final compositions. The grays do differ slightly painting to painting, ranging from gunmetal to battleship—or, in other words, not much at all. Yet despite these limitations, or more likely because of them, the work almost always captivates.

With several large paintings now encircling the small gallery at Blackston, floor to ceiling, her latest work conveys an added power without giving up its compositional secrets. Feldman paints fast, one session per piece, enlarging from sketches into dynamically simple shapes, drips and all. There’s a high-wire quality in the way she makes this happen. The paintings succeed in how she balances the gray and white between figure and ground. While the grays lay on top of the white as a figure, the white also pushes into them, forcing them to ground. The line between the two tones can have an optical quality as this teetering dynamic is played out. The overall effect resembles the flickering, color-deadening sense of space illuminated by an old fluorescent light.

At Blackston, Feldman brings her paintings up to a line of cartoonish legibility, with close-set, similarly styled works interacting like square panels in a comic strip, but with only the most cryptic storyline. Killer Instinct (2014) looks like the face of an angry monkey. Spirit Merit (2014) could be a ghost. Gut Smut (2014) is a puff of smoke. In the side room, the monkey faces return in two animated sets of four smaller paintings. Yet any coherent reading quickly disappears to the margins, just as the gray of Open Omen (2014) migrates to the edges, leaving only a white void.

Katherine Taylor, Bark Feet (2014)

I first met the artist Katherine Taylor almost exactly twenty years ago, hiking the Appalachian Trail between Franconia Notch and Mount Moosilauke, New Hampshire. A year apart from me as an undergraduate at Dartmouth College, she was the sophomore leader on my freshman orientation trip. So perhaps I should claim to be among the first to pay this sculptor a studio visit. Taylor has never stopped working with the woods of New England and Upstate New York in forging a vision between nature and the imaginary world. Now on view at Skoto, her latest show reveals what she has learned in translating her impressions of New Hampshire bark into zoomorphic sculptures of remarkable craft.

For Bark Feet (2014), what at first seem like outré elephant-foot stools are in fact cast sculptures that are the result of an elaborate process, one that begins with her hiking tubes of silicone caulk into the deep woods to make molds of tree bark. Working in a foundry in the Basque region of Spain, Taylor then multiplies, turns, and folds these impressions into an uncanny semblance of animal skin—even finding ways to mimic the cracked appearance of toenails—which is finally here rendered in aluminum. In other examples, the bark becomes the rind of a sliced fruit or the meat of a nut. Her best work lets these textures speak for themselves, without over-manipulation. In all, Taylor demonstrates the unity of the natural world, with a continuous surface connecting with our own sense of wonder.

Installation form Robert Otto Epstein: Sleeveless

Robert Otto Epstein updates the obsessive craft that defined the Pattern and Decoration movement of the 1970s with the Casualist tendency of the current outer-borough aesthetic. Inventiveness and humor mix with Epstein’s own obsessive abilities, with Bauhaus-quality work inspired by Cosby sweaters and baseball cards. For “Sleeveless” at the Bushwick-based 99¢ Plus Gallery, Epstein showed monochromatic drawings of graphite on hand-gridded paper that referenced patterns from the garment industry: Sleeve for Sweater (2012), Knitting Pattern for Cozy Sweater (2012), and Sleeveless Cardigan (2012). In the place of Epstein’s fun sense of color, the work had a quiet melancholy, as though paying homage to the nameless artisans who once made such garments, and to the people, now gone, who once wore them. While this exhibition had a short run, through mid-December Epstein returns for a group exhibition called “Thread Lines” at The Drawing Center that will explore similar themes while “unraveling the distinction between textile and art.”

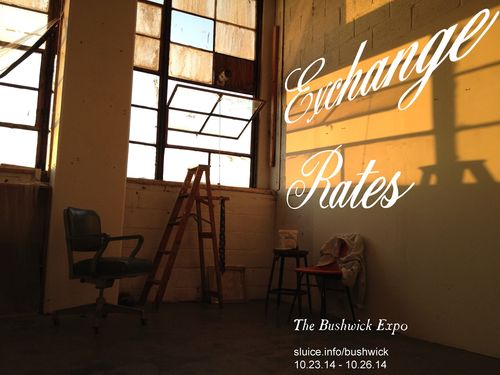

A final note about an inaugural event called “Exchange Rates: The Bushwick Expo” to take place between October 23 and 26, aligning with Bushwick’s semi-annual “Beatnite” gallery Friday. As I remarked in this space last June, lifestyle culture will increasingly attempt to tap the artistic energy of this outer-borough neighborhood. “Bushwick Takes the Spotlight” read a New York Times headline last month about a new condo development, in an article that began by mentioning “the appearance of a scantily clad, twerking Miley Cyrus at a recent party.”

There is much to be had in twerking with this neighborhood’s artistic reputation even as—or perhaps because—such acts will inevitably will lead to its degradation. Yet “Exchange Rates” looks to be one attempt to expand the cultural conversation from within. Paul D’Agostino of Centotto and Stephanie Theodore of Theodore:Art, two Bushwick stalwarts, have paired with London-based Sluice_ (the underscore isn’t a typo) to place thirty international galleries within twenty Bushwick venues. The four-day collaboration should carry the neighborhood’s DIY approach to an event of broad scope. Whether the mainstream press chooses to note only Miley Cyrus is an open question, although the run promises much to look at and even more to see.