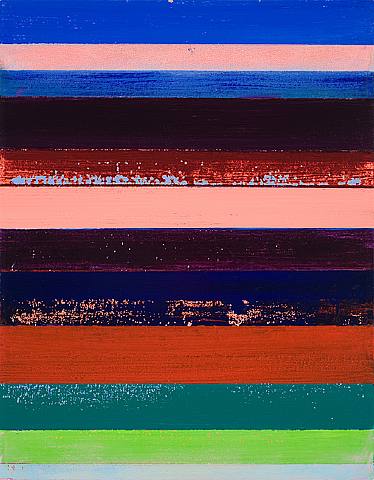

Kim Uchiyama, Geo (2009), courtesy Lohin Geduld Gallery

THE NEW CRITERION

October 2010

Gallery chronicle

by James Panero

I first heard the term “classical abstraction” during a studio visit with the painter Tom Evans, one of those majestic wild birds still roosting in an artist-in-residence loft downtown. Evans used the term to distinguish his own gestural, romantic canvases from the restrained compositions of some of his contemporaries. Like him, these fellow artists came of age during the post-minimalist revival of oil on canvas in the 1970s. Unlike him, they have created work that tends to feature repetitions and variations of color and line, usually tucked into rigorous, self-imposed systems that can extend over multiple canvases.

For Kim Uchiyama, whose paintings are now on view at Lohin Geduld Gallery, “classical abstraction” is right.[1] The term indicates her admiration for the canon of abstract art and a contentment to work within abstraction’s established parameters. Rather than strive to create the next hit on the avant-garde hit parade, Uchiyama digs deep into the riches of a century-old tradition. The title of the show, “Archaeo,” reflects the approach.

“Classical abstraction” is also appropriate because it underscores a commitment to compositional order. Uchiyama’s recent body of work consists of horizontal bands of color in various arrangements over several canvases of uniform size. The program might sound unrewarding and look problematic in reproduction, but in person interesting things happen when the classical concerns of symmetry, proportion, and simplicity

are matched with the freedom of abstract painting.

Uchiyama uses vertically oriented canvases, twenty by sixteen inches, to explore the abstracted horizon line. She arranges strata of colors, bottom to top, that mirror the layering of paint on the canvas itself. A band of blue might be stacked on top of a band of pink, just as the blue line is painted over an application of pink paint.

She focuses on the beauty of form by stripping away concern for content and expression. The systematic division of her canvases creates an additional spareness that allows the properties of the materials to become more apparent. As a reward for close viewing, her best work reveals the subtleties of paint on canvas—the opacity of the pigments, the texture of the brushstrokes.

The rhythm of her composition opens up nuances that one might otherwise miss, or that other artists might deliberately conceal, in more complex designs. Her work has certainly taught me to become a more attentive viewer. Uchiyama’s canvases are like classroom chalkboards spelling out the lessons of her generation, which often involve the mechanics of painting.

In her latest work, Uchiyama shows the archeology of her paintings through quiet, controlled gestures. Colors peek around other layers. Bright complementary colors leech out around the darker stripes on top of them, energizing the compositions with an aura of light while revealing the history of the work, showing the older paint below. Uchiyama even distresses some top stripes of paint, pulling away paint with adhesive to expose the depths.

Like all classical abstractionists, Uchiyama must balance order with variation. She sometimes imposes too much control, making her paintings seem like innocuous design. I worry that her program of stripes, carried so thoroughly through the work in this show and beyond, can itself become limiting. Mid-career artists often risk working too well in a certain mode. An overworked skill can spoil the freshness of an artist’s project. Uchiyama’s finest work is therefore her roughest, where she leaves more to chance. At Lohin, Geo (2009), the most distressed canvas of the series, also happens to be her best.

When I wrote about John Dubrow’s last show at Lori Bookstein Fine Art in May 2008, I praised him for his effortful canvases. Dubrow is an abstract artist painting representational scenes that expose the construction of pictorial space. Now back at Bookstein, his paintings can be battlegrounds, places where he might wrestle for years with a single composition—oil on canvas by way of hammer and forge.[2] The results reveal the drama of execution, where countless layers of paint muscle the images into place and still contend with an uneasy truce of surface treatment and depth.

This battle becomes particularly pitched in his cityscapes. I first saw the epic painting Prince and Broadway (2002–2010), of pedestrians at a crosswalk, back in 2003. Dubrow has been fighting with it ever since. Whether it was finished two, four, or even eight years ago is an unanswerable question. It certainly seemed good and done, but Dubrow is clearly not one to leave well enough alone.

And yes, this painting has improved through its latest reworking. The tonalities of reflected light are sharper. More significantly, the figures have come forward. A male pedestrian has lost his suit jacket, revealing a white shirt underneath that pulls him up and makes him a more haunting presence.

It is remarkable to realize how intimately Dubrow must know these canvases by now. He reaches in and ever so slightly tweaks his dioramas in paint. Each move, which he documents through photographs, becomes another frame in a stop-gap animation that gives the images their life.

When Dubrow turns to portraiture, the pressing issues of pictorial space are far less acute. Here the psychological presence of his sitters takes up its own space and lets Dubrow ride a little in the backseat, giving this body of work a relative ease. Without the aid of photographs or even preparatory drawings, Dubrow carries his large canvases with him to the subjects’ homes and offices for the sittings, then works on them more back in the studio.

The personalities of the subjects come through in their relationship to the space around them. The painter Tine Lundsfryd, with legs crossed on a swivel chair, spins out from the confining opening of a doorway. The poet Mark Strand glares out from his desk with arms folded, his expression reflected in his glass desk. A single flash of color often shines out of these muted spaces—the pink light in a window, the blue of a chair—assigning a dominant tone to each of the subjects.

This exhibition, which pairs the cityscapes with the portraits, shows how Dubrow is learning to borrow from each to inform the other. The figures in his cityscapes continue to come forward, while his portraits are settling into the space around them.

The exhibition “In the Light of Corot,” organized by Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects, considers how a selection of twentieth-century and contemporary painters has contended with this pillar of the Barbizon school.[3] “In the Light” not only considers Corot’s treatment of light, in particular during his early Italian sojourn, but also asks deeper questions about the continued relevance of landscape “in light of” Corot’s accomplishments.

For a few artists who came of age mid-century and passed through the push-pull lessons of Hans Hofmann, the calling of Corot sent them in a new direction. In the 1960s, Paul Resika traveled to Italy in the footsteps of Corot. In this exhibition, Harvey displays a large, warm Resika landscape of a hillside road, one of the few to survive a fire in the artist’s studio. Here the title Landscape Near Volterra (1967) is literal. Resika locates us near Volterra, but still several miles away from the hilltop town that Corot depicted in his iconic 1834 landscape. Unlike the Corot, Resika’s landscape also plants our feet firmly within the world in front of us, where the country road leads off to the tiny town dotting the horizon. The grand painting is a knowing homage of its source material, “near” but not altogether “in” the mode of the master.

Maybe “Near the light of Corot” would have been a better title for this show, with all of the paintings arrayed in a Venn diagram of various proximity to the plein-air master. An excellent Fairfield Porter from 1959, Wareham, Rt. 6, shares as much light with Corot as an overcast New England day shares with sun-kissed Umbria. Yet the distance gives it a visual honesty, something I found lacking in Lennart Anderson’s seascape The Terrace (1964). Here an Italianate balcony replete with marble statuary in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts should have been returned cod to Bellaggio. Seymour Remenick’s Corotesque renderings of the warehouses around Philadelphia likewise seem displaced, too plein-air sweet for down-and-out Philly. With Midday Sun (2008), the excellent young painter Sangram Majumdar seems to be working in the light of Dubrow more than Corot. The contemporary painter Israel Hershberg meanwhile turns a cool photorealist eye to the places of Corot’s Italy—here the grand tourist with an oil-on-canvas point and shoot.

David Kapp knows how to paint. I am less certain he knows what to paint. His cityscapes, now on view at Tibor de Nagy, display uncanny painterly skill.[4] Decisive brushwork fills his canvases with excitement. If only I could say the same for the images he chooses to represent.

Kapp takes on the city by looking down on the city. He depicts faceless crowds at crosswalks, the snarl of cars on their evening commute, and city streets stretching off into the distance. Whether he relies on photography or not, his compositions have more of a cinematic than a painter’s eye—not precisely photorealism, but rather photoimpressionism. His shots are hardboiled—the cockeyed angles and streaking headlights and long shadow lines of film noir—but finished with a dollop of Vaseline on the lens. The mixing of the styles does not work for me. The facelessness and sharp angles also seem like urban cliché—disengagement masquerading as attitude.

Oil on canvas should impose its own order on what it depicts, but, for the most part, the paint here merely glosses over the world within. A notable exception is Walker (2009–10). This painting has us again look down on a pedestrian, but here the figure is alone, not just a face in a faceless crowd. A curb cuts across the painting diagonally. We can see the roofs of two parked cars on top. What distinguishes this work is how the paint takes charge of the image. The compositional division of the curb line is striking. The work is relatively spare. The rendering of the pavement is particularly appealing—flattened out with a knife. Rather than the mere depiction of pavement with some flourishes on top, this feels like smooth pavement itself, equally present in our world and its own.

[1] “Kim Uchiyama: Archaeo” opened at Lohin Geduld Gallery, New York, on September 8 and remains on view through October 9, 2010.

[2] “John Dubrow: New Paintings” opened at Lori Bookstein Fine Art, New York, on September 15 and remains on view through October 30, 2010.

[3] “In the Light of Corot” opened at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects, New York, on September 8 and remains on view through October 2, 2010.

[4] “David Kapp: Recent Paintings” opened at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, on September 11 and remains on view through October 20, 2010.