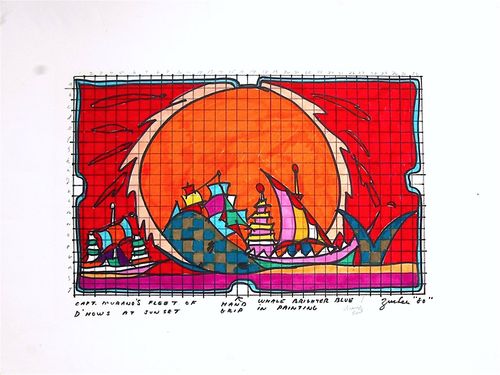

Meryl Meisler, Self-Portrait, A Falling Star North Massapequa, NY, January 1975 Vintage gelatin silver print, printed 1975, 10 x 8 inches/Courtesy: Steven Kasher Gallery

THE NEW CRITERION

April 2016

Gallery Chronicle

by James Panero

On “Meryl Meisler” at Steven Kasher Gallery, New York; “The Invitational Exhibition of Visual Arts” at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York; and “Michelle Vaughan: Generations” at Theodore:Art, Brooklyn.

Photography becomes powerful when it combines inscrutable complexity with instinctive attraction. While we may understand little of a medium that engages our lives with ever-greater frequency, we can be compelled by its magic the less we know. After all, on its surface a photograph presents a moment of refracted light captured through near unfathomable means, either through digital impulses or analogue emulsion, imprinted largely without comment for our interpretation of its point of origin. Yet this surface works in contrast with a photograph’s absorptive depth, a space that draws us in almost automatically, and where we find reflections of our own emotions in a light of strange and often disorienting affinities.

In his 1980 book The Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes drew a distinction between a photograph’s cerebral propositioning, what he called the studium, and its emotional hook, which he called the punctum. I like to think that Woody Allen hit on something similar a few years before Barthes in his character Alvy Singer’s famously ill-received words with Diane Keaton’s Annie Hall: “Photography’s interesting, ’cause, you know, it’s—it’s a new art form, and a, uh, a set of aesthetic criteria have not emerged yet.” For which a subtitle appears as translation: “I wonder what she looks like naked?”

The photographer Meryl Meisler arrived in New York City in the mid-1970s at just the Annie Hall moment, bringing her own sensibility for revealing the disquieting humor of urbane sophistication in dialogue with middle-class Jewish values. Her work is both a fascinating document of a lost time and a delivery vehicle for its intoxicating, riotous sweetness. “I see funny,” she recently said. “People come out funny.”

Now at Steven Kasher Gallery, Meisler is showing her earliest photographs from the treasure trove of her rich body of work, which has only surfaced within the last few years since she retired from a career as a New York City Public School teacher in Bushwick, Brooklyn.

For an unassuming retired civil servant, Meisler has been on an astonishingly meteoric rise since her work first started coming to light following the publication of two recent books of her photography, A Tale of Two Cities: Disco Era Bushwick andPurgatory & Paradise: SASSY ’70s Suburbia & The City.

The titles speak to the boundaries Meisler once regularly crossed with her camera: from her family home in the Long Island suburb of North Massapequa, to the demimonde of the clubs and dancehalls of the city’s punk, disco, and burlesque scenes, to the school children of Bushwick finding life in the burned-out streets following the blackout riots of 1977. Rather than indulging in the decadence and decay, Meisler looked for the humanizing touch in the wreckage, the sleaze, and the schmaltz, often positioning herself and her own maturation at the comedic fulcrum.

The selection at Steven Kasher brings together Meisler’s Massapequan adolescence with her first penetrating forays into the nightlife of the city. Black and white and square in format, the photographs draw on the work of Diane Arbus, an acknowledged influence, in both their stark appearance and offbeat eye. Yet Meisler manages to capture a warm light that ultimately eluded Arbus, a depressive who took her own life in Greenwich Village just a few years before Meisler’s own arrival.

In contrast to the stripped-down punk aesthetic of the city, Massapequa of the 1970s was high suburban rococo. In Meisler’s photographs, the postwar refuge of middle-class flight have become its own overgrown cul-de-sac. Clean mid-century modern lines have been inundated by the wild patterns and overwrought furniture indicative of a period we might call the South Shore Regency.

Meisler first took up the camera while studying illustration at the University of Wisconsin in the early 1970s. Returning east, she enrolled in classes with Lisette Model, the photographer who had taught Arbus. Meisler first turned the camera on herself, posing in her childhood uniforms back home. In Self-Portrait, The Girl Scout Oath, North Massapequa, NY, January 1975, she sits in the family “rumpus room” giving the three-finger salute while wearing her old uniform and former hair braids, both saved by her mother. Meisler looks out with a deadpan gaze from the near-camouflage patterns of the matching cushions and drapes. The odd symmetry of the scene is undercut by an incongruous barbell intertwined by her feet, sweatily wrapped in grip tape and on loan, it turns out, from her brother. Another image, Self-Portrait, A Falling Star, North Massapequa, NY, January 1975, finds her in what appears to be an old tap-dance outfit, smiling as she slides headfirst off the La-Z-Boy. Look closer and her frivolity amidst the suburban order of the decorous side cabinet and framed wall prints appears imperilled by a porcelain tiger prowling in her direction out of a collection of chinoiserie.

Urban archeologists will undoubtedly appreciate the grit and glamor Meisler soon found in the city’s nightlife. Stringer contracts and late-night tenacity brought her past the velvet rope of Studio 54, backstage at cbgb’s, and into even more risqué after-hour venues, where she also worked as a hostess. Yet through a 1978 ceta Artist grant, Meisler then returned to North Massapequa to create a series of photographs on Jewish identity for the American Jewish Congress. Back in the hair salons, wedding halls, dens, bedrooms, and Rosh Hashanah dinner tables, she found a world even more exotic than the exotica of the adoptive city she temporarily left behind.

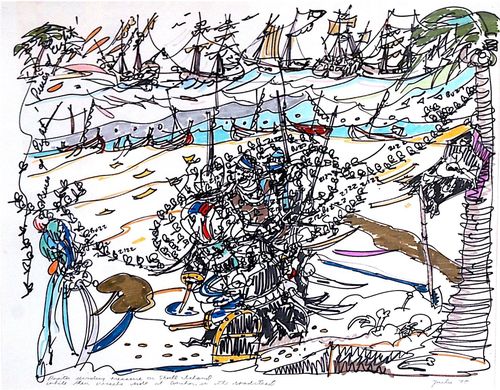

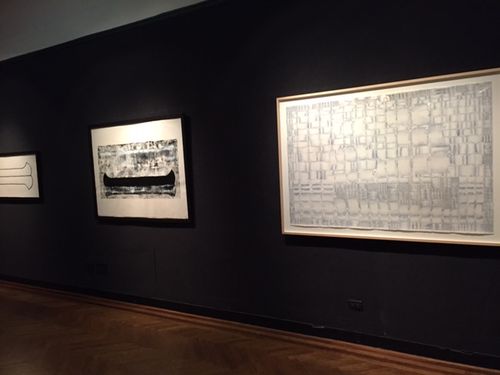

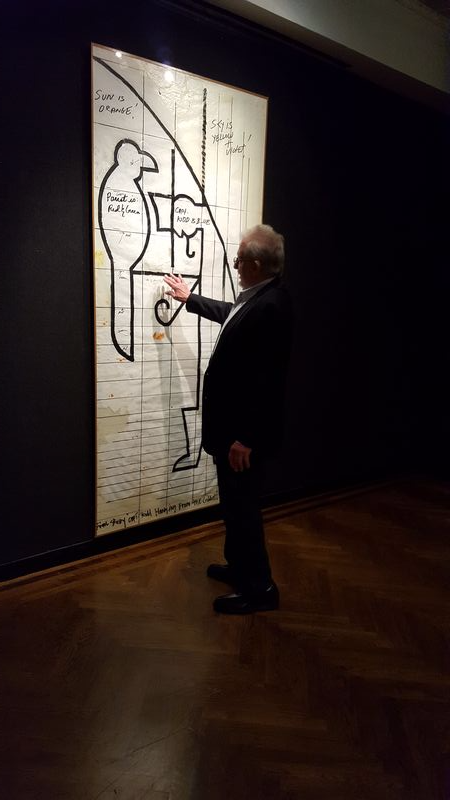

Installation view of the 2016 Invitational Exhibition of the American Academy of Arts and Letters with work by Cullen Bryant Washington, Jr., Lisa Hoke, Guy Goodwin, and Patrick Strzelec/Photo: James Panero

Now through April 10, “The Invitational Exhibition of Visual Arts” offers one of the few annual opportunities for outsiders to visit the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the fantastical honors society encased in beaux-arts amber at the far end of Archer Huntington’s Audubon Terrace, at Broadway and 155th Street.

Behind the scenes, we can only imagine that this “invited” exhibition is a battleground of competing interests among the Academy’s august membership. Yet what regularly results is often one of the best annual survey shows of serious and lively contemporary art. Well displayed, and spanning a wide variety of media and styles, from abstract sculpture to hyperrealistic figuration, light installations to watercolor sunsets, this year is no different, with thirty-seven artists selected from two hundred nominations, displaying over one hundred works spread across the Academy’s campus.

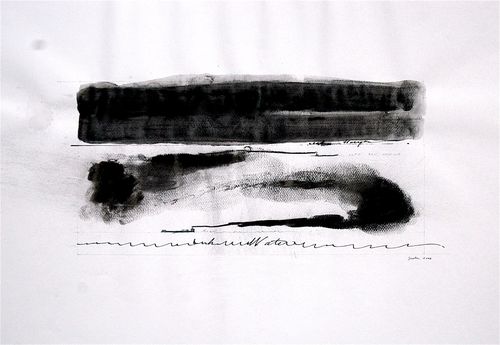

The Invitational is the first part of the Academy’s series of honors. The Academy then annually distributes $250,000 to the artists of the exhibition through awards, prizes, and purchase funds, with the winners returning each May for the Academy’s “Exhibition of Work by Newly Elected Members and Recipients of Honors and Awards.” This year’s recipients, just announced at press time, reveal the Academy’s catholic interests—and good judgment. Top prizes go to Guy Goodwin’s intriguing colorful abstractions of acrylic, tempera, and cardboard; Anthony McCall’s sculptural light installation created by “computer, Quicktime movie file, video projector, and haze machine”; Nancy Mitchnick’s painterly abstractions found in the profile of Detroit’s demolished buildings; Joan Snyder’s joyful kitchen-sink assemblies of oil, acrylic, papier mâché, rope, wooden hoop, burlap, silk on linen, etching fragments, rosebuds, twigs, and glitter; and Lee Tribe’s haunting, dissolving portraits in charcoal and steel. Also honored are the lyrical-, fantastical-, and hyper-realisms of Patricia Patterson, Carmen Cicero, and Aleah Chapin, and the expressionistic abstractions of Chuck Webster. Still others, including the fraught patterning of McArthur Binion and the riotous sunsets of Graham Nickson, have been purchased for donation to American museums.

All told, the “Invitational Exhibition” again confirms that no single style holds an exclusive ticket to that “funicular up Parnassus,” in Alfred Barr’s choice phrasing—and how fortunate we are to have exhibiting institutions that operate outside of museum mandates. While the exhibition is free, visitors should be mindful of the Academy’s limited hours, while also leaving time to see the reinstallation of the Charles Ives Studio, Anna Hyatt Huntington’s sculptural program lining Audubon Terrace, and the jewel-box museum of the Hispanic Society, now fortunately chaired by the Metropolitan’s legendary retired director, Philippe de Montebello.

I would point out that the Bushwick galleries of 56 Bogart Street are having a particularly strong month, but exceptionalism there now seems to be the rule. Among standout exhibitions are the sound pioneer Audra Wolowiec at Studio10, the disaster artist Joy Garnett at Slag, a vertiginous, cubistic interpretation of the L Train by Isidro Blasco at Black and White Gallery, and a group painting show at Life on Mars featuring Glenn Goldberg, Steve DiBenedetto, and Brenda Goodman, along with their selection of younger artists in the project space.

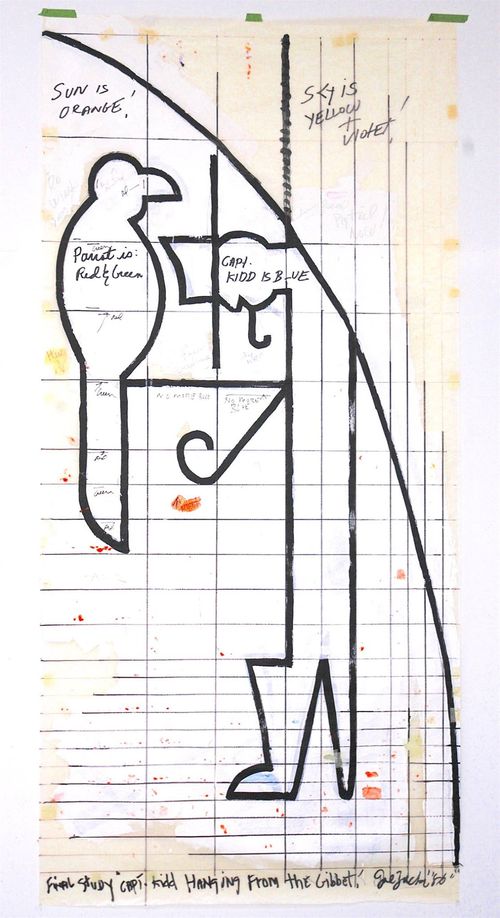

Michelle Vaughan, King Charles II of Spain, coefficient 0.25, 2013, Archival digital print, 30 x 22 inches/Courtesy: Theodore:Art

An exhibition called “Generations,” on view at Theodore:Art, may be the most unnerving. The artist Michelle Vaughan uses a variety of copying processes, from digital reproduction to pencil drawings, to explore the history of European portraiture—in particular, the “consanguineous unions in Europe’s royal houses” from the fifteenth through the eighteenth centuries. By overlaying portrait faces of the Spanish and Austrian lines of the Habsburg dynasty—such as Spain’s King Philip IV and Mariana of Austria, both his niece and second wife—Vaughan demonstrates how their shared physiognomies revealed increasingly compromised genomes through generations of planned and ill-fated inbreeding.

Working with genetic historians, Vaughan uses artistic means to show how the repeated intermarrying of the Habsburgs led to high and ultimately destructive “inbreeding coefficient numbers” that eventually “ranged higher than the offspring produced by a brother and sister” due to sequential uncle–niece marriages and prior intermarrying. For anyone who has wondered at the strange faces staring back at us from a Velázquez, it is both interesting and terrifying to realize that these deformations were not the mannerisms of Spanish style but most likely artistic improvements over genetic reality.

A degraded digital print of a 1685 portrait by Juan Carreño de Miranda of Charles II of Spain, the son of Philip IV and Mariana of Austria, is the most haunting of the exhibition. With a quarter or more of his genome consisting of identical pairs, or “coefficient 0.25,” Charles II was riddled with recessive abnormalities, leading to pronounced mental and physical retardation. Known as “the Bewitched” (el Hechizado), Charles was defined by his elongated face, a protruding “Habsburg jaw,” and a tongue so overgrown that he could barely speak or chew. Just as this print’s digital data has dissolved into a cloud of bits, Charles was an ineffective and impotent monarch, childless and heirless, whose rule marked the end of the Spanish Habsburg line.

Vaughan brilliantly overlays science, art history, and creative practice in a confluence of interests. Here is a museum-quality exhibition (attention, Met Breuer) that will change the way I look at museum portraiture.