THE NEW CRITERION, April 2017

On the “Invitational Exhibition of Visual Arts” at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, “Paul Resika: Empty” at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects, the “Talking Pictures 1st Invitational” at 106 Van Buren Street, “Bewilder: New Work by Brece Honeycutt” at Norte Maar & “Rough Matter: New Work by Rebecca Murtaugh” at Stout Projects.

The 2017 “Invitational Exhibition of Visual Arts,” at the American Academy of Arts and Letters through April 9, is the survey of contemporary art that isn’t the Whitney Biennial.1

Far up the river from the Meatpacking District, at 155th Street and Broadway, the “Invitational” is well removed from the art world’s sociological pageants downtown. In a space given over to artistic sensitivities, the “Invitational” is also my favorite of the cultural season, with one of the few broad contemporary exhibitions that remains truly receptive to the transformative power of art.

This all is due, no doubt, to the private, artist-based leadership of the Academy, an honors society for architects, artists, writers, and composers. Today it is still underwritten by a 1914 founding endowment created by the philanthropist Archer M. Huntington. Unfettered by institutional mandates, or the not-so-invisible hand of commercial backers, the “Invitational” brings together art for art’s sake—this year, thirty-five contemporary artists selected from 165 nominees submitted by the membership. Funds supplemented through donations by late members such as Jacob Lawrence and Childe Hassam underwrite prizes for the artists in the exhibition. Some of the awards are dedicated to purchasing and then donating selected work in the show to American museums.

This year the Academy’s Art Award and Purchase Committee includes the artist-members Judy Pfaff, Lois Dodd, Mary Frank, Robert Gober, Yvonne Jacquette, Bill Jensen, Joan Jonas, Dorothea Rockburne, and Joel Shapiro. Rumor has it the selection of work can become contentious among the membership, but the result is always a well-honed distillation, with divergent art finding new connections—aided by a curator who knows how to hang art within the Academy’s rambling rooms on its beaux-arts campus of Audubon Terrace.

Caetlynn Booth, Selvage, 2014–16, Oil on panel,

On display at the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

This “Invitational” brings together the guerrilla realism of the late Arnold Mesches with the fugal portraits and contrapunto abstractions of Phong Bui and the totemic figurines of Vanessa German. There are the apotropaic bird sculptures of Jonathan Shahn with the swampy luminism of Caetlynn Booth, my painter-colleague here at The New Criterion. There are the color-rich abstractions of Andrea Bergart reflecting the inchoate shapes of Helen O’Leary near the diminutive color blocks of Janice Caswell and the synapse-singeing installations of Hap Tivey. A video work by Kakyoung Lee, along with related drypoint prints, brings to mind the animation of William Kentridge, while Walter Robinson, Beverly McIver, and others all give varying interpretations to painterly figuration.

The independence of the “Invitational” continues as a remarkable relic of a more uncompromised age, no doubt aided by its uptown remoteness. At a time when most other artistic institutions are heralding their “public engagement” (those windows and balconies at the Whitney!), the Academy’s remove clears the air for its artists and gives this exhibition an unalloyed intensity.

Last month the paintings of one great academician, Paul Resika, were on view on the Lower East Side at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects. In a haunting exhibition called “Empty,” Harvey assembled a small but brilliant selection of Resika’s paintings from the early 1990s to the present—work that Harvey has seen first hand as they were created.2

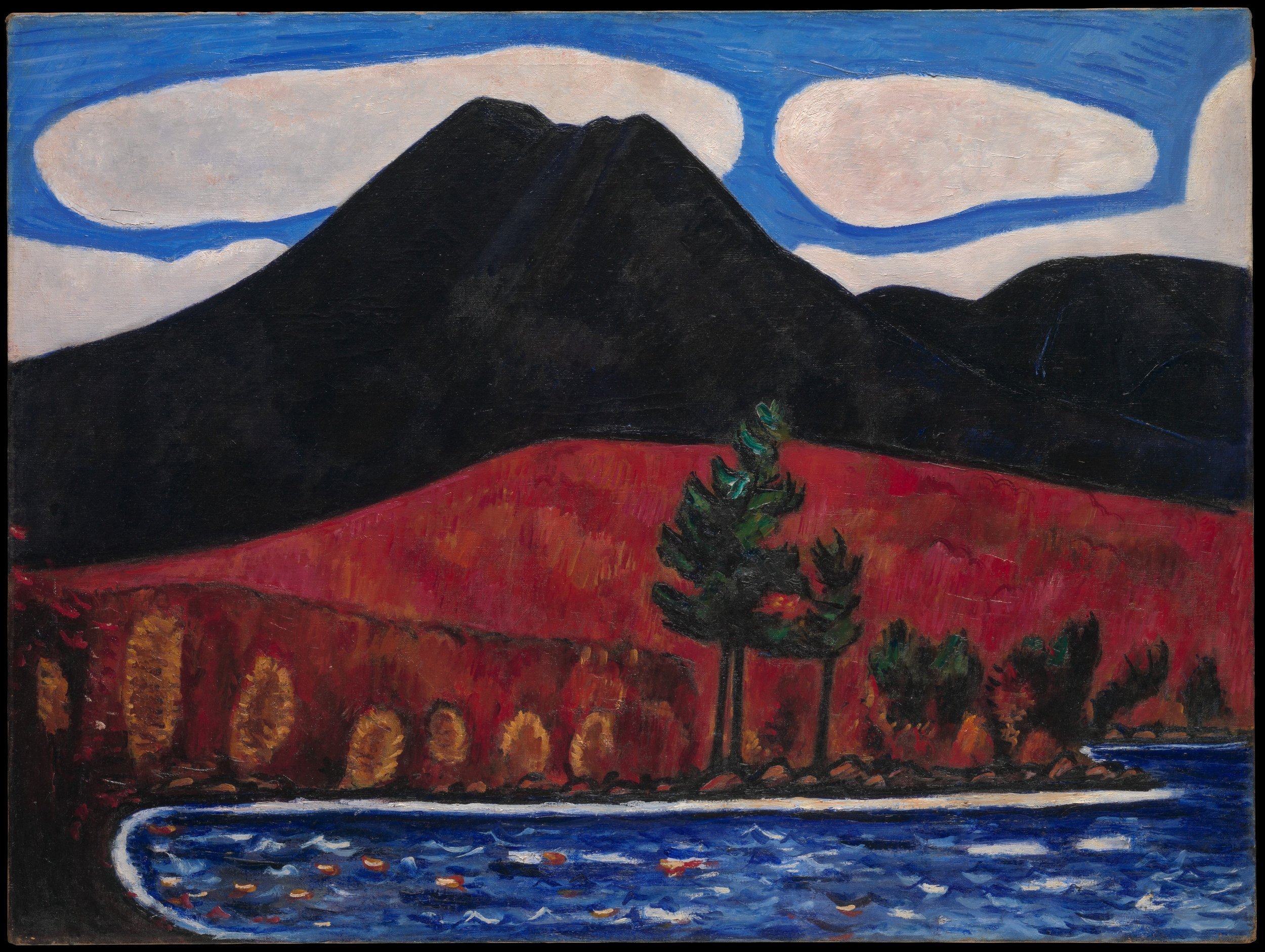

Paul Resika, Blue Sail, 1997–98, Oil on canvas.

For such an omnivorous painter as Resika, who has found nourishment in both the abstractions of his mentor Hans Hofmann and the figurations of the Old Masters (who are also his mentors), what was brought together here was absence: empty boats and shacks, paintings cleared of people and inundated with color. “Like getting lost in Venice at night,” Harvey writes in his catalogue introduction, “the empty spaces of de Chirico, Carrà, and Sironi are echoed in Resika’s boathouse architecture and empty vessels, redrawn in cool blues and hot oranges.” Paint has become both the water and the mirror, with angular shapes and reflected lines becoming their own presence. For someone who has been painting for seven decades across the full landscape of art, a unifying theme has been such tonal poetry—well reflected in this sensitive exhibition.

In case you were wondering, it’s been a good season in Bushwick. The symbolic abstractions of Lawrence Swan at Schema Projects; the urban impressionisms of Kerry Law at Centotto; the cosmic figures of Elisa Jensen and the grounded portraits of Janice Nowinski at Valentine; the painterly fire of Arnold Mesches at David & Schweitzer; the “river women” of Odetta gallery with the most uncanny sculptures of New York’s East River and Newtown Creek by Fritz Horstman and Kathleen Vance: just some of the shows in an abundance of energetic offerings.

At the same time, Bushwick’s artists have been seen ranging farther afield: the supple, constructivist collages of Austin Thomas at Chelsea’s Morgan Lehman; the finely painted dreamscapes of Ryan Michael Ford nearby at Asya Geisberg; and Rico Gatson, at Ronald Feldman, stealing the show in an otherwise frivolous Armory fair, with the power of pattern connecting across time and space to find deep meaning.

This past month, one of my first stops in Brooklyn took a right turn in Bushwick for the neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant. I have written about the homespun cultural institutions of the painter Cathy Nan Quinlan in this space before (“Gallery Chronicle,” January 2012). In the mid-2000s, Quinlan opened the “ ’temporary Museum of Painting (and Drawing)” out of her loft apartment in Williamsburg. There she turned her interest in the outer-borough painting scene into a self-made institution founded “to exhibit and discuss contemporary painting in all its various forms, whether fashionable or unfashionable (at the moment).” When Quinlan moved to Bed-Stuy, she broke ground on a “new wing” of the ’temporary Museum called “My Collection”—this time based out of her row-house living room.

Over a few weekends last month, in the basement of this same building on Van Buren Street, Quinlan put together what she called the “Talking Pictures 1st Invitational,” named this time after her weblog in which she illustrates contemporary art shows and recalling the initiatives of more established institutions such as the American Academy.3

The line-up of the “Talking Pictures 1st Invitational”

Curated by Paul D’Agostino, Jeffrey Bishop, and Quinlan, who selected four artists each, the “Invitational” served as background for an underground, as it were, evening symposium

—this one discussing an interview Bishop conducted with Susan Sontag in 1981. The reference was obscure; the setting far beyond the tourist circuit. So the initiative had a personal appeal, disconnected from the world, blissfully out-of-step with outside mandates.

The event was remote, even for me, and I missed the talk, but the “Invitational” was remarkable, when I later stopped by, for the quality of the painters it brought together: the gridded abstractions of Meg Atkinson, the spectral realism of Fred Valentine, and the (new to me) evocative landscapes of Cecilia Whittaker-Doe. I was also struck, as with Quinlan’s other projects, by the show’s homemade authenticity. I would call the spirit “do it yourself,” or diy. But D’Agostino recently corrected me on that usage. As the founder of Centotto, now Bushwick’s oldest continuous apartment gallery, D’Agostino says he prefers DI. Or, simply, “do it.”

Another Bushwick institution, now decamped further along the J-train to the sylvan neighborhood of Cypress Hills, is the non-profit Norte Maar. This month, Brece Honeycutt is exhibiting her textile and sculptural work here in a solo exhibition called “Bewilder,” with collages by the sound artist Audra Wolowiec in the back room.4

Brece Honeycutt, bewildered: yellow haze, 2017, Eco-dyed damask textile and eco-dyed thread.

I became closely aware of Honeycutt’s work, and her working method, when she collaborated recently on a poetry chapbook with my wife, Dara Mandle—published, I might add, by Norte Maar. Based in Sheffield, Massachusetts, Honeycutt makes resists and dyes out of the hardware and weeds she finds on her farm. Working with paper and discarded linen, she then creates earthy abstractions by submerging these materials in wildflower baths while bundled with rusty washers and nails. The effect is like a shadow, with pentimento traces of history—but the visual impact can also be allusive, not always rising above the level of craft.

At Norte Maar, Honeycutt has now gone back into her textiles and papers with additional interventions. In some examples, she has created free-form and hanging sculptures out of an assembly of paper prints and found objects—whimsical work that calls to mind the anthropomorphic scrap-metal sculptures of Richard Stankiewicz. In others, the introduction of thread, which she weaves into the linens, structures her compositions and serves as drawn lines. Here I found the white, undyed linens of her “winterfield” series most striking. By introducing shapes and textures distilled in deeply felt and spare abstractions, Honeycutt recalls farmland vegetation—as well as the “women’s work” that once stitched farm life together.

Back in Bushwick, in the gallery building of 56 Bogart Street, the sculptures of Rebecca Murtaugh are now on view in a solo exhibition at Stout Projects.5

Resembling modernist shapes lost at the bottom of the sea, Murtaugh’s sculptures are encrusted specimens, living forms animated in paint. Paint itself is her sculptural medium—enamel paint, in bold colors, emulsified and applied like cottage cheese to her armatures.

Rebecca Murtaaugh, Accretion: Gladiolus and Ultraviolet, 2017, Wood, paint, and mixed media.

Until recently, these underlying forms resembled minimalist sculptures—symmetrical, angular shapes with donut holes, or “apertures,” at the center. Now at Stout Projects, Murtaugh has taken a more biomorphic turn. Her influence here is Henry Moore, or even more so Isamu Noguchi. Murtaugh’s latest shapes are seemingly lifted from nature. As she builds them up in an additive way, free and without the structural supports of earlier work, the sculptures become dynamic and internally engaged. Murtaugh’s series of “feelers” consists of C-shaped forms turned in on one another—like cells observed and colored under a scanning microscope. Others called “paddle and burrow” are more like nests drilled into slabs of porcelain. Accretion: Gladiolus and Ultra Violet (2017), the showstopper, is a growth nesting in the pocket of three free-standing branches, repellently alluring and appealing toxic—all at once.