PHILANTHROPY MAGAZINE

SUMMER 2011

Outsmarting Albert Barnes

by James Panero

In assembling his art collection, Barnes outsmarted the world. In crafting his foundation, Barnes outsmarted himself. By James Panero July 1, 2011

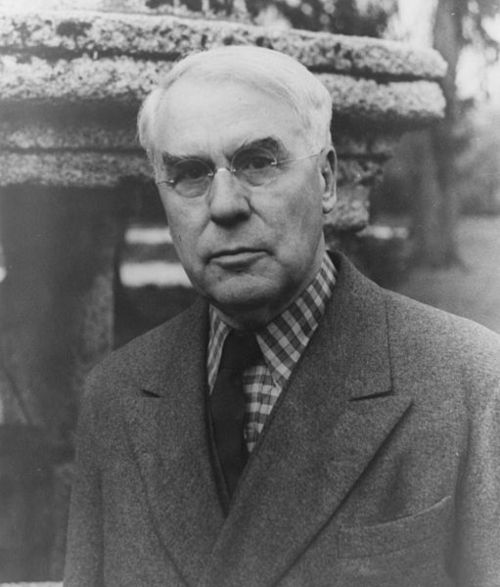

Albert Coombs Barnes was a brilliant man. As a student, Barnes emerged from one of Philadelphia’s toughest neighborhoods, eventually earning a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania and studying chemistry in Germany. As an entrepreneur, he made a fortune through the mass production of anti-blindness medicine. As a businessman, he timed the sale of his business perfectly, selling at the peak of a surging market. As an art enthusiast, he amassed one of the world’s finest collections of post-Impressionist and early modern paintings. As a philanthropist, he created a school—not a museum—where some of the world’s finest works of modern and post-Impressionist painting were studied in strict accordance with Barnes’ self-designed pedagogical principles.

All in all, the same brilliance that created a legacy for Albert Barnes would ultimately undo his legacy. Since the time of Barnes’ death in an automobile accident in 1951, the Barnes Foundation has been a case study in how an institution, created by a brilliant mind with clear intentions, can become irrevocably damaged through overly restrictive operating guidelines, unanticipated leadership problems, and the competing missions of other organizations and institutions. Much attention has been paid to the forces at work against the foundation, but in fact the seeds of destruction were sown by the hands of Barnes himself. As history has proven, decisions he made in life imperiled the perpetuity of his collection after death.

Barnes made every effort to preserve the vision of his creation after his death. For the past 60 years, what we have seen at the Barnes is what Barnes put there himself. At this moment, however, Barnes’ art collection is being removed forever from the walls he built for it. Barnes knew he was creating something unique in the annals of American art. He was also right that outside forces would emerge to alter his project after his death. What he never anticipated was that the very defenses he put in place to preserve his collection would eventually contribute to its undoing.

Street Fighter

The rise of Albert Barnes is an only-in-America success story. For decades, it has fascinated biographers like William Schack (Art and Argyrol), Howard Greenfeld (The Devil and Dr. Barnes), and John Anderson (Art Held Hostage). Each of these biographies is instructive, and on one essential point, they all agree. Barnes was a conflicted figure, a man of titanic intelligence, unflinching will, and self-destructive pride.

John Barnes, Albert’s father, had been a butcher before the Civil War. Four months after enlisting in the Union Army, he lost his right arm at the Battle of Cold Harbor. Deprived of his trade, he made ends meet with a veteran’s pension and a job as a letter carrier. He settled in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, where he married and had four boys. Kensington was—and is—a hard, working-poor neighborhood, the home of Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky Balboa. Boys learn early on to become street fighters. Barnes certainly did.

Lydia Barnes, Albert’s mother, came from hearty Germanic stock. She introduced her sons to painting, and encouraged them to take up music. A devout Methodist, she took young Albert to African-American camp meetings and revivals, where the eight-year-old boy was deeply moved by gospel music and spirituals. But perhaps most importantly, she encouraged Albert to excel in his studies. He earned a spot at Philadelphia’s prestigious Central High School, and later, a scholarship at the University of Pennsylvania. Barnes put himself through college by tutoring, boxing, and playing semi-professional baseball, earning $10 per game. By age 20, he was a medical doctor.

Barnes preferred research to clinical practice, and moved to Germany to study advanced chemistry. He eventually partnered with Herman Hille, a promising young chemist who had earned a doctorate at the University of Würzburg. Together, the two men returned to the States and began to hunt for new commercial products. They considered several possibilities—cheesemaking, biscuit mixes—before settling on finding an improved silver compound with antiseptic qualities.

At the turn of the 20th century, silver nitrate was widely used as an antiseptic. It was dabbed, for instance, in the eyes of every newborn infant, as a precautionary measure against blindness from gonorrheal infection, and was regularly administered for inflammatory conditions in the eyes and nasal passages. In many cases, however, silver nitrate had serious side effects; in all cases, it had a caustic sting. Hille and Barnes discovered a way to create a silver compound that retained its antiseptic qualities but overcame its caustic irritation. They submitted the product for clinical trials at the University of Pennsylvania, where its value was immediately recognized. The partners named the compound Argyrol. It would make both of them very wealthy indeed.

Barnes was especially good at running the business. He convinced Hille not to file for a patent—doing so would require disclosing the exact chemical composition and production process—and instead focused on waging ferocious lawsuits against anyone who tried to use the Argyrol brand name. He marketed Argyrol directly to physicians—not, as was common at the time, to pharmacists—and quickly took his product overseas. He slashed production and transportation costs by manufacturing the crystallite—pharmacists mixed the actual solution—and his payroll never exceeded a dozen employees. In 1907, five years after setting up shop, Barnes and Hille cleared $250,000 in profits (roughly $5.8 million today).

Relations between Barnes and Hille soured, and by 1908 Barnes bought out his partner for $350,000. It was the deal of a lifetime. Now the sole proprietor of the A. C. Barnes Company, he was said to be a millionaire (or today, $23-million-aire) at age 35. For the next 20 years, his business boomed; dozens of states required the application of Argyrol to the eyes of every newborn infant. Running the business took less and less of his time. Increasingly, he devoted his considerable energies to collecting art—and developing an educational method for teaching it.

“He has broad shoulders, stands an inch or two short of six feet, and weighs about a hundred and ninety pounds,” reads a New Yorker profile from September 1928. “His square determined jaw, large head, and piercing blue eyes, which take in everything about him with quick, suspicious glances, top off a solid beefiness that would suggest an Irish police captain if it were not for the seething, restless energy.”

In July 1929, Barnes sold his business to the Zonite Products Corporation for a reported sum of $6 million. He placed almost all of the proceeds in government bonds. His timing could hardly have been better. Had he held out a few more months, the stock market crash and Great Depression would have likely scuttled any sale. Even if Barnes had somehow kept his business going, the appearance of commercial antibiotics in the 1930s would have rendered Argyrol obsolete. Entering the Depression, Barnes’ fortune and his philanthropic vision never looked brighter.

Medici of Merion

Barnes first became acquainted with modern painting through William Glackens, a high-school friend and prominent painter in the Ash Can School of American realists. Glackens was Barnes’ first (and only) art buyer—in 1911, Barnes gave him $20,000 to make purchases in Paris—and he introduced Barnes to Paris’ avant-garde circles in 1912. There, Barnes met Gertrude Stein and her circle; Gertrude’s older brother, the art critic Leo Stein, became a longtime friend of and influence on Barnes. It was the first of many such trips. Over the next few decades, Barnes became a force among buyers. He was the first to recognize Chaim Soutine, for example, and news that Barnes had bought all of Soutine’s work made the Lithuanian an overnight sensation in Montparnasse.

“I just robbed everybody,” Barnes once gloated. In 1913, he acquired Picasso’s Peasants and Oxen for $300—about $6,500 in 2010—and he picked up dozens more canvasses for a dollar apiece. For one of Matisse’s most significant paintings, The Joy of Life, he paid $4,000. According to biographer John Anderson, the most Barnes ever paid for a painting was $100,000. In exchange, he acquired Cézanne’s The Card Players. “Particularly during the Depression,” he said, “my specialty was robbing the suckers who had invested all their money in flimsy securities and then had to sell their priceless paintings to keep a roof over their heads.”

Through dogged persistence, Barnes put together what many critics consider the world’s finest collection of post-Impressionist and early modern paintings. In his lifetime, Barnes grew his collection to house 69 Cézannes—more than in all the museums in Paris—as well as 60 Matisses, 44 Picassos, and an astonishing 181 Renoirs. The 2,500 items in the collection include major works by (among others) Rousseau, Modigliani, Soutine, Seurat, Degas, and van Gogh. There are also pieces of African sculpture, Asian prints, medieval manuscripts, decorative metalwork, as well as Old Master paintings, including works by El Greco, Peter Paul Rubens, and Titian.

In terms of numbers alone, the art in Barnes’ collection is estimated today to be worth between $20 and $30 billion. While Barnes never intended his collection to be a trophy room—and indeed the price of art still seems to be an alien consideration when contemplating the pieces on Barnes’ walls—the numbers are nonetheless staggering. By way of contrast, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation showed $33.9 billion in assets in 2009. Although John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie were vastly wealthier than Albert Barnes, the Barnes Foundation has assets 10 to 20 times greater than either the Carnegie Corporation or the Rockefeller Foundation.

But the full value of Barnes’ collection would not be apparent for years. As he was putting it together, Barnes suffered a stinging humiliation from Philadelphia’s establishment art critics. In April and May of 1923, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts hosted an exhibit for some 75 of Barnes’ pieces, including sculptures by Lipchitz and paintings by Soutine, Modigliani, Matisse, Pascin, and Picasso. Critical reaction was almost uniformly brutal. It was a “series of seemingly incomprehensible masses of paint, known as landscapes” (Philadelphia Inquirer). “It is as if the room were infested with some infectious scourge” (the North American). “It is hard to see why the Academy should sponsor this sort of trash” (Philadelphia Record).

Barnes was enraged. He penned a series of fiery letters to his critics, threatening to drive them out of town and informing Edith Powell of the Philadelphia Public Ledger that she would never be a real art critic until she had relations with the ice man (and, in the words of biographer William Schack, “he went into explicit detail”). He likewise came to loathe established Philadelphia art institutions, calling the Philadelphia Museum of Art a “house of artistic and intellectual prostitution,” and asserting that the main function of museums “has been to serve as a pedestal upon which a clique of socialites pose as patrons of the arts.” Perhaps most of all, he came to despise casual viewers of art. Years later, at an informal talk at Pembroke College in Providence, Rhode Island, he decried people who attended exhibits and “went about exclaiming, ‘Oh, isn’t that nice, isn’t that lovely?’ and [let] their children slide on the floor.”

Barnes had long planned to house his collection outside of Philadelphia, and the reaction to his exhibit hardened his resolve. Before the exhibit, in 1922, Barnes had employed the lawyer and law professor Owen J. Roberts, who went on to become an associate justice of the Supreme Court, to draw up the foundation’s governing documents. In creating the foundation, the entity designed to protect his collection, he brought the same attention to detail that informed the arrangement of art on the walls.

In 1925, the Barnes Foundation opened its doors as an educational institution. Crucially, the Barnes Foundation was formed as a school, with restricted access, and not as a museum, which would have been open to the public. The collection was housed in a new estate in Lower Merion, five miles from Philadelphia. Situated in an already established arboretum, which became the purview of his wife, Laura, the Barnes Collection was arranged in an elegant new building designed by Paul-Philippe Cret, a graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts. Soon after its opening, the Saturday Evening Post called the facility “a walled-in little universe.” Ranging over 12 suburban acres, Barnes had “a $500,000 palace built out of cream-colored limestone imported from France,” some of the “rarest trees and shrubs in the United States,” and “a tall iron-spiked fence encircl[ing] the grounds protectively.”

Within those carefully guarded walls, the Barnes collection became even more than the sum of its remarkable parts. Barnes did not just collect a single time period or style of art. Nor did he segregate his collection by type. Unlike what one finds in almost any other institution housing art, Barnes integrated his collection and arranged it by the appearance of colors and shapes. Among his collection of modern masterpieces, Barnes mixed in significant examples of ancient, medieval, Renaissance, and non-Western art. He also arranged examples of craft, most notably metalwork and furnishings, among his walls of art.

Nothing in the collection was left to chance. Every work of art connected to the next. “Barnes’ interest was in the living nature of artworks,” writes the critic Lance Esplund. “He set up dialogues among works of various periods and diverse styles to emphasize similarities where most museums emphasize the distinctions. Barnes understood that the ancient Greeks, Titian, Rubens, Renoir, and Matisse, far from disconnected, are links in the chain.”

Barnes was known to open his doors to factory workers and struggling artists but reject the applications of the rich and famous, often with a dismissive letter signed by Fidèle-de-Port-Manech, Barnes’ pet dog. T. S. Eliot’s request was turned down with a one-word answer: “Nuts.” Matisse, on the other hand, made the cut. Barnes positioned The Joy of Life midway up the stairs of the Cret building. In the early 1930s, Barnes further commissioned Matisse to paint a monumental mural, known as The Dance II, in the lunettes above the windows of the foundation’s main gallery. Matisse, in turn, called Barnes’ school the only “sane place” to see art in America. “The Barnes Foundation,” Matisse said in an interview, “will doubtless manage to destroy the artificial and disreputable presentation of the other collections, where the pictures are hard to see—displayed hypocritically in the mysterious light of a temple or cathedral.”

The Old Guard

It was sunny and hot on July 24, 1951, and Barnes seemed distracted after his Sunday dinner at Ker-Feal, his country farm. Barnes decided to return to Merion. He loaded his dog, Fidèle, into his Packard and began the 25-mile drive. There was a stop sign on Route 29, near Phoenixville—Barnes had objected to its installation and refused to observe it. He blasted through the intersection and barreled directly into a 10-ton trailer truck. The 79-year-old’s body was thrown 40 feet from the car. Fidèle, near dead herself, would not allow state troopers near her crumpled master. She had to be shot.

Such fierce, protective loyalty would characterize the first generation of the Barnes Foundation. For the generation after the death of Barnes and his wife, majority control of the Barnes Foundation board remained in the hands of Barnes’ disciples, or the “Old Guard,” as they were known. Leading the Old Guard was Violette de Mazia, a petite Frenchwoman who had been at the foundation since the mid-1920s. Much about de Mazia, including her origins and arrival in the States, remains a mystery, but this much is certain. She was the spiritual heir, prime disciple, and (allegedly) long-time mistress of Barnes. From 1951 until her death in 1988, de Mazia was the driving force at the Barnes Foundation.

De Mazia was steeped in the Barnes Foundation’s educational practices. Deeply impressed by John Dewey’s Democracy and Education (1916), Barnes believed that the development of cognitive skills, rather than the memorization of facts, was the key to education. To understand art, then, everything you need to know is right there in front of your eyes, if only you understood how to see it. In arranging his art on the wall, Barnes thus dispensed with labels, period rooms, chronological order, and the solemnity of your typical white-walled gallery. Instead, with his art hanging floor to ceiling, Barnes let the harmony of shapes and forms sing for itself. He wanted his collection to enliven the eye, not confound it with facts. He believed his students would be able to see the visual connections between disparate works, styles, and periods, and learn from those associations without the benefit of words.

De Mazia clearly subscribed to the educational mission and intent of Barnes in her stewardship of the foundation. She rigorously upheld his pedagogy. She would often dress in colors meant to tease out details in the paintings, or dance in front of an artwork to suggest the movement of its lines. In one little-noticed respect, however, de Mazia may have departed from Barnes’ preferences. Barnes wanted his foundation to educate working men and women. (“In order to get the honest reaction of a simple mind to art,” the New Yorker noted in 1928, Barnes “called in a negro truck-driver who was delivering coal, plumped him down in front of a Cézanne, and asked for an opinion.”) Under de Mazia’s leadership, classes were only offered on Tuesdays, and always during working hours. The foundation adhered faithfully to Barnes’ teaching methods and curriculum, but instead of reaching out to factory workers and truck drivers, it was increasingly educating wealthy housewives and retirees.

Crucially, Barnes also placed considerable restrictions on the operations of the foundation. He limited the salaries of the foundation’s employees without mechanisms that could account for inflation. He restricted any changes to the collection or to the facility’s grounds. Perhaps most importantly, he restricted the investment of the foundation’s endowment, restrictions to which the Old Guard scrupulously adhered. During Barnes’ lifetime, the indenture granted that the endowment could be invested in “any good securities.” After his death, however, the corpus could only be invested in federal, state, and municipal bonds. Over time, this restriction severely eroded the endowment. In 1951, the value of the foundation’s endowment was $9 million (or about $75 million in 2010). For a collection housing what would today be billions of dollars in art, such an endowment would be slight compared to the need to safeguard the artwork against decay, theft, and litigation while still upholding the educational mission of the foundation.

Yet the real damage to the endowment came in the inflationary decades after Barnes’ death. “In the aftermath of the Vietnam War and the Arab oil embargo,” writes John Anderson in Art Held Hostage, “inflation soared and the endowment took a beating. By the early 1970s, says former Girard banker and Barnes trustee (1983–89) David Rawson, the endowment ‘had lost money. It was down to five and a half or maybe six million dollars.’ By now, the trustees, says Rawson, had had to invade the principal, just to make ends meet. . . . The $9 million in the endowment in 1991 was the equivalent of barely $1.7 million in 1951 dollars.”

Many of the other restrictions Barnes placed on his collection further limited the ability of the foundation to raise revenue in the manner enjoyed by most American museums: through ticket prices, the lending of artwork, the sale of pieces in the collection, the selling of reproduction rights, and on-site fundraising events. The foundation was increasingly asset-rich and cash-poor. Its chief assets were as illiquid as they can be—not only could they be not be sold or exchanged, they couldn’t even be moved. All of which, of course, was by Barnes’ own design. In fact, if anyone were to give “society functions commonly designated receptions, tea parties, dinners, banquets, dances, musicales, or similar affairs” at the Barnes collection, according to the indenture, any resident of Pennsylvania could sue to stop it and “have his total legal expense paid by the Barnes Foundation.”

Repeatedly, Rawson made recommendations for the foundation to file a petition in the Orphans’ Court of Pennsylvania to allow the endowment to be invested in a more diversified portfolio, including securities, rather than exclusively in public bonds. While this would be contrary to Barnes’ stated wishes, such a move, he maintained, was the only way the endowment could keep up with an inflationary climate that Barnes had not anticipated while crafting his indenture.

In retrospect, it may appear unfortunate for the foundation that the other trustees voted these motions down. According to this line of thinking, the board’s decision may have honored the letter of Barnes’ indenture, but it imperiled the collection by not allowing the endowment to keep pace with the foundation’s operational needs. The early trustees appear to have preserved the rules of the bylaws at the expense of the collection and the overall health of the foundation. It seems like a reversal of priorities.

But that is not quite fair to de Mazia and the Old Guard. They had compelling reasons, both practical and principled, to adhere to the letter of Barnes’ investment instructions. As a practical matter, they were well aware of the threat of outside litigation. In particular, they knew very well how much Walter Annenberg, owner of the Philadelphia Inquirer, had detested Albert Barnes. Annenberg led a lawsuit against the foundation in February 1952—just seven months after Barnes’ death—demanding that the collection be open to the public. He lost the case but laid the groundwork for a newspaper crusade against the foundation, culminating in April 1958 with the state Attorney General bringing suit. This time, the Barnes Foundation was forced to concede on several points, including opening to the public, by appointment, on two days every week. As a practical matter, the Old Guard understood the need to stick to the letter of the indenture, if it was to have credibility demonstrating its commitment to donor intent in the courts.

At the same time, de Mazia and her fellow trustees had principled reasons to uphold Barnes’ investment instructions. They would have known about Barnes’ experience in the Great Depression, when bonds proved a far better investment than stocks. But there was a larger point, as well. Barnes, they knew, was a proud New Deal Democrat. His preferences for public debt rather than private stock very likely reflected his ideological sympathies. (Barnes himself did not use the phrase, but his indenture seems to call for a prototypical form of mission-related investment.) Barnes never made clear which was a higher priority—maintaining the corpus in government securities, or maintaining the integrity of the collection—and thus left his successors without guidance on a crucial point of intent.

The Old Guard viewed the bylaws of the Barnes Foundation as equally fixed as the arrangement of the paintings on its walls. In many cases, these considerations were in harmony. For example, in honoring Barnes’ wishes that his collection remain intact and not be added to or sold, the trustees preserved the collection, the mission of the foundation, and the stipulations of the indenture. In their treatment of the endowment, however, this fidelity worked against the overall long-term viability of the foundation. This much is certain. Early on, it was apparent that the board had to negotiate between conflicting imperatives—conflicting imperatives that had been put in place by Barnes himself.

Lincoln’s Leadership

In September 1988, a bedridden, 89-year-old Violette de Mazia gave up the ghost. She had outlived Barnes by 38 years, throughout which time she had faithfully guarded the foundation. With her departure, the board faced a succession challenge. Leadership would devolve to people who never knew Barnes. Once again, the protocols Barnes implemented—in a document that he revisited and revised many times—proved a serious impediment to carrying out his overall intent.

In Article IV of the original 1922 bylaws of the foundation, Barnes detailed the mechanisms whereby new members would be nominated to the board following the death of himself and his wife. The first vacancy was to be filled by election of a person nominated by whichever financial institution was then treasurer of the foundation. Subsequent nominations would be made by the board of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the board of the University of Pennsylvania. In other words, three different nominating bodies would fill vacancies on the board. Those bodies would then have the power to nominate candidates for those seats in perpetuity, rotating and balancing power among themselves.

Those plans finally came undone in the spring and summer of 1950, after Barnes exchanged a series of increasingly insulting letters with Harold Stassen, the newly installed president of the University of Pennsylvania, whom Barnes decreed was “what psychologists term a ‘mental delinquent,’ variously known to laymen as a ‘dumb bunny, false alarm, phony.’” Barnes had clashed with his alma mater before, but now was committed to removing it from the future of his foundation.

On October 20, 1950, less than a year before he died, Barnes amended the foundation’s indenture. “No Trustee,” he wrote, “shall be a member of the faculty or Board of Trustees or Directors of the University of Pennsylvania, Temple University, Bryn Mawr, Haverford, or Swarthmore Colleges, or Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.” Instead, following the nomination of a member submitted by the financial institution, the amendment codified that, “the next four vacancies . . . shall be filled by election of persons nominated by Lincoln University, Chester County, Pennsylvania.”

When Barnes gave Lincoln the authority to nominate four of the foundation’s five trustees, it was a testament to his progressive attitudes on race. Lincoln was a small, historically black university, whose graduates included Thurgood Marshall, Langston Hughes, and Cab Calloway. Late in his life, Barnes had become close to Horace Mann Bond, the president of Lincoln who also happened to be the father of the civil rights leader Julian Bond. When the elder Bond invited Barnes to lecture on art (for $9.25 per hour) during the 1950–51 school year, Barnes was “so overwhelmed with joy and admiration,” he wrote back, “that I danced the cancan.”

The amendment would radically change the future of the Barnes Foundation. Curiously, Barnes never informed Lincoln of his plans; the school learned of the change in 1959, and then by accident, eight years after Barnes had died. Perhaps Barnes believed that the strength of his indenture, just like the power of his collection, did not require an expert to comprehend. In any event, the Lincoln that Barnes knew in the 1940s was not the same institution in the 1980s, by which time it was a faltering state-subsidized school. Its leadership was not always as inspired as Bond’s, nor was Barnes’ foundation as financially strong in the 1980s as it had been in 1950.

Within a few years of Lincoln gaining control of Barnes’ nominating process, a politically connected lawyer by the name of Richard Glanton was elected president of the Barnes Foundation. Glanton, an African American from a small, Appalachian town in Georgia, was, like Barnes, a self-made man with a fearless, combative will. Unlike Barnes, Glanton was outgoing, Republican, and very much interested in belonging to Philadelphia’s innermost elite circles. Handsome, charming, and ferociously ambitious, Glanton could not have been more dissimilar from the studious and withdrawing de Mazia. Even more different would be how they ran the Barnes Foundation. Where de Mazia sought to preserve the Barnes in its 1950s state, Glanton was eager to institute a wide range of changes.

Glanton immediately pointed to the foundation’s run-down physical plant, combined with the weakness of its endowment, and argued the need for breaking the Barnes indenture. Initially, he planned to sell off items in the collection. In November 1990, he petitioned the Montgomery County Orphans’ Court for permission to deaccession $15 to $18 million worth of paintings. After a heated public outcry, the board voted down Glanton’s plan in June 1991. But Glanton was more successful in his second effort, convincing the Pennsylvania courts to allow the foundation to send the art collection on an international tour, to publish a glossy catalogue of the collection, and to open the institution to paying crowds. All of these moves were widely criticized by Barnes’ students—and expressly forbidden by Barnes’ indenture.

But, facing a depleted endowment, Glanton argued, they were necessary. These activities, however controversial, raised much-needed revenue. In August 1992, he convinced the court that, while the Cret building was closed for renovations, it would make sense to take some 80 items on a one-time worldwide tour, with stops scheduled in Paris, Tokyo, Toronto, Washington, Fort Worth, and—to cap it off—the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In all, the tour netted some $16 million for the foundation. While the paintings were off the walls, they generated enough money to pay for the $12 million overhaul of the Cret building, and left another $4 million for the slowly growing endowment.

Glanton was not satisfied. Even after the success of the tour—over 30 months, some 4.5 million people had viewed the traveling exhibit—it was not clear how the foundation could continue to raise operating income. Glanton proposed increasing the admissions fee (to $10) and tripling the number of annual visitors (to 120,000). In order to do so, the Barnes Foundation would need to expand its parking lot. Neighbors on Latch’s Lane were already uneasy with the proposed expansion, but they objected strenuously to adding parking. Glanton sued, invoking federal statutes designed to break up the Ku Klux Klan. He accused neighbors of “thinly veiled racism,” and pushed hard to get them to buckle. Glanton believed the lawsuits would settle early, but when they dragged on for years, costing the foundation over $6 million and further eroding the endowment, they began to call into serious question the viability of the Barnes.

Glanton’s tenure as president of the Barnes came to an end in February 1998, when he was ousted, four votes to one, by his fellow board members. From Glanton’s proposal to sell major artwork to his breathy charges of racism, his continued leadership became untenable. His endless litigation had weakened Barnes’ already fragile endowment. He had departed from the indenture on several key points—taking items from the collection on a worldwide tour, publishing a glossy catalogue, and working to make the Barnes into a partially self-funding enterprise—thereby alienating those most dedicated to Barnes and his legacy. But whatever else may be said of him, and whatever his motivations, Richard Glanton was in complete harmony with Albert Barnes on one key point. Both men were devoted to the independence of the Barnes Foundation.

All in all, the crises of the Lincoln years were the consequence of decisions that Barnes had made years earlier. Barnes’ 1922 bylaws ensured checks and balances on board nominations, with alternating entities nominating different seats. Under the 1922 rules, no single entity nominated a majority of the foundation’s board members. The 1950 amendment did away with this balancing mechanism, meaning that Lincoln effectively controlled four of the five seats. The fate of the Barnes Foundation became irrevocably linked to the health of one other organization—one which, for all of its historic strengths, was never properly acquainted with the demands of administering an art school and art collection, even in Barnes’ lifetime.

Bailing Out Barnes

Years of litigation, coupled with the ongoing issue of access to the collection, did considerable damage to the foundation’s attempts to solicit major donations. “I never, in a million years, dreamed that I would have had such a problem raising money. Not at a place like the Barnes,” says Kimberly Camp, who became the foundation’s executive director after Glanton.

The Barnes Foundation was primed for a bailout. Seen in this light, the next front in the battle over the Barnes was controversial but not entirely unexpected. A wide partnership of Philadelphia-area foundations—led by the Pew Charitable Trusts, the Annenberg Foundation, and H. F. (“Gerry”) Lenfest’s foundation—emerged with a major pledge. They offered $150 million in private and public funding to support the Barnes—on two major conditions. The first was the dilution of Lincoln’s nominating influence on the Barnes board by the addition of 10 new seats, for the reported purpose of expanding fundraising opportunities. The second was the removal of the Barnes Collection, in its entirety, from its home in Merion to a larger, new facility in downtown Philadelphia.

Each condition clearly violated the terms of the indenture, and together they represented the outcome that Barnes probably feared most. The board of Lincoln University at first objected to the dilution of its control, but eventually relented. Two reasons are usually given for the school’s change of mind. First, then–Attorney General Michael Fisher met with the Lincoln board. As Fisher explained in a 2009 documentary called The Art of the Steal, “I had to explain to them [Lincoln’s board] that maybe the Attorney General’s office would have to take some action involving them that might have to change the complexion of the board. Whether I said that directly or I implied it, I think that they finally got the message.” Second, state aid to Lincoln was ramped up, and then-Gov. Ed Rendell took a leading role in the school’s capital campaign. Rendell has always insisted that there was never a “quid pro quo.”

So in October 2002, the board of the Barnes Foundation filed a petition with the Montgomery County Orphans’ Court, seeking to change the terms of the indenture. In December 2004, Judge Stanley M. Ott ruled that the foundation could move its collection to Philadelphia and abide by the other conditions of the grant, which would effectively rewrite most of Barnes’ indenture. Many of Philadelphia’s civic leaders were elated. Former Mayor John Street has praised a relocated Barnes for having the “economic impact of three Super Bowls, without the beer.” Rendell maintains that “this collection should be shown to as many people as humanly possible in the best, easiest-to-get-to setting that we can do. This was always a no-brainer for me. It wasn’t a tough decision to make at all.”

The practicality of these arguments is difficult to refute, but for one fact. Barnes created his institution specifically to stand apart from such economic imperatives. Even back in the 1920s, Barnes could see the future of most museums, and he was right. Art was becoming just another asset class, and many museum leaders would seek to monetize their assets in whatever way possible. Today the accepted practices of mainstream museums would horrify Barnes even more than they did in his day, with bequested art horse-traded for more popular pieces, cookie-cutter exhibits arranged by era on sterile, white walls, and name-brand artists sold in reproduction in the gift shops of blockbuster exhibitions.

A number of people have come to the defense of Barnes and his legacy. “Foundations are nonprofit corporations,” said the Los Angeles Times critic Christopher Knight in The Art of the Steal. “We’re used to hearing about corporate takeovers with for-profit corporations. But this was a nonprofit corporate takeover.” Julian Bond, the son of Barnes compatriot and Lincoln president Horace Mann Bond, likewise decried the move: “The art belonged to him. He had the right to do with it as he chose, and these people, these vandals, stepped in and took it away from him.” Critics have called the new facility, still under construction and set to be completed within a year, a “McBarnes.” “While the new Barnes’ galleries will supposedly replicate the scale, proportion, and configuration of the existing galleries,” says Lance Esplund, “it will be through a Frankenstein’s monster-like revivification.”

All of which brings us back to Barnes himself. Representatives for the Barnes and the Pew Charitable Trusts both declined to participate in this story, but it is possible to reconstruct their arguments from public statements and court testimony. Rebecca Rimel, president and CEO of Pew, has argued that “this is not only honoring the donor’s intent but making sure that the collection will be available for generations to come.”

Perhaps. On the one hand, it is difficult to see how Albert Barnes would have ever consented to having his collection removed from Merion. (It is especially difficult to imagine how he would have accepted the undoing of his foundation by the successors of Walter Annenberg.) On the other hand, it is not exactly clear to what extent Pew, Annenberg, or Lenfest are obligated to defer to the wishes of Albert Barnes. Donors, whether individual or institutional, pursue a wide variety of causes. In a free society, many of those causes will be mutually exclusive. Barnes wanted his collection intact and in Merion. Pew, Annenberg, and Lenfest want to make downtown Philadelphia a center for world-class art. Both goals are perfectly legitimate—indeed, on their own, entirely admirable.

The funders who worked to relocate Barnes’ collection could tell themselves that they had no trust relationship to Barnes and therefore they could not violate his donor intent: only Barnes’ board could do that. But breaking the independence of the Barnes Foundation—and moving the collection into a museum that, however extraordinary, would horrify Barnes himself—nonetheless comes with a serious cost. These actions undermine the general principle of donor intent. They set a precedent that could discourage future donors from believing that their intent will be honored. All philanthropy involves an act of trust between giver and recipient. These actions erode that sense of trust, to the detriment of future philanthropy.

On July 3, the Barnes in Merion closed its doors. Over the next few months, the collection will be moved to a new, 93,000-square-foot facility near the Philadelphia Museum of Art on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. The new facility is scheduled to open in May 2012, and is intended to reproduce the collection as laid out by Barnes himself, with rooms of the same size and proportion as those in Merion. In addition, it will house a large conservation laboratory, as well as additional amenities for visitors, including a restaurant, store, and gathering spaces. The new facility will be able to accommodate upwards of 250,000 visitors annually.

Finishing Strokes

While the Barnes collection is next to flawless, the Barnes Foundation was deeply flawed from its inception. Much of the blame for this mistake must revert to Barnes himself. In writing his indenture, Barnes could have kept the investment strategy more open to the judgment of the treasurer, or he could have established trustee succession plans that retained internal checks and balances. He did not, however, and his foundation has suffered the consequences.

Barnes rightly recognized the genius of his creation. The precision of the Barnes collection—the arrangement of art on the walls—made the collection great. The over-precision of Barnes’ indenture—the many stipulations meant to keep that precise arrangement intact—rendered the foundation brittle. Barnes was accustomed to enjoying total control over his foundation. Perhaps he could not imagine it entrusted to the hands of others. In any event, the indenture was over-engineered, lacking operational flexibility and strong board succession mechanisms that might have allowed it to survive into the far future.

Albert Barnes always seemed to thrive on conflict, and his legacy is fittingly conflicted. He built his collection to bring art to ordinary workers, but shared his treasures with shockingly few people. He instituted a pedagogy that was intended to bring democracy to learning, and enforced it with a ruthless, autocratic will, allowing no one to question its propriety. He was a private man who never shied from public fights; a man of great intelligence and artistic sensitivity who, when challenged, could instantly turn petulant and obscene.

But perhaps the most conflicted aspect of his legacy is this. In creating his collection, Barnes outsmarted the world. In crafting his foundation, Barnes outsmarted himself.