James writes:

The phrase “Inspired by the Motion Picture” does not generally inspire confidence on Broadway. More often than not, we’re talking about a popular movie repackaged for the discount crowd. But what if your inspiration is “An American in Paris,” the 1951 Academy Award-winning MGM musical starring Gene Kelly? And what if you are the English choreographer Christopher Wheeldon, one time dancer and resident artist at New York City Ballet?

In the case of “An American in Paris,” the new musical that opened this week at the Palace Theatre, we are talking about something truly inspiring. In his Cast Notes, Wheeldon says he “honors the artists whose film inspired this new stage version.” That film, directed by Vincente Minnelli from a script by Alan Jay Lerner, was a lightweight romance between an American painter Jerry Mulligan, who stayed in Paris after the liberation, and a French girl, Lise Bouvier. The plot revolves around a cast of supporting characters that includes Jerry’s society patron Milo Roberts (who is interested in more than his paintings), a successful French singer named Henri Baurel (who is engaged to Lise), and a composer friend named Adam Cook (who helps sort it all out).

What set the movie apart was its final fifteen minutes. In what has been called the greatest dance number on film, and with a production that cost of half a million dollars, the painter Jerry Mulligan, played by Kelly, dances with Lise, played by Leslie Caron, through a dream sequence of Paris as imagined through his artwork. The score for the number is George Gershwin’s 1928 symphonic poem, “An American in Paris,” which gives the film and the musical its name.

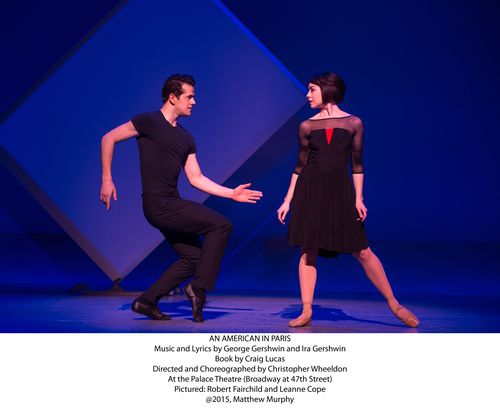

Wheeldon began here and built out his musical from this balletic denouement. A new book by Craig Lucas also adds some true grit to the story. The 1951 musical did little to acknowledge the war. For that matter, it barely acknowledged the twentieth century: Jerry still lives in the Paris of La bohème. On Broadway we are now clearly contending with the hangover of war, with characters with new backstories and new last names: Lise Dassin (Leanne Cope) is a Jewish refugee hidden by Henri’s family, who fought for the Resistance; Adam Hockberg (Brandon Uranowitz) is an injured Jewish American GI, Jerry is suffering from shell shock. Sometimes Lucas overly burdens the story: it was smart to recast Henri (Max von Essen) as a struggling singer, but an insinuation that he “does not fancy women” and therefore hides his own secret muddies the plot; Hockberg also overly plays up his own impotence.

Yet overall these additions give the musical a modern urgency that propels the performance. It starts in a swirl, with the Nazi flag of the occupation pulled down and turned back to the colors of the Republic, all in one flowing movement. With costumes and sets by Bob Crowley, the scene changes are seamlessly handled by the performers, who wheel out and dance around the mobile set pieces. Backdrop projections imagine Paris as a sketchbook that gets redrawn through each scene.

Robert Fairchild, the NYCB principal who, like his sister, has (temporarily?) traded Balanchine for Broadway, fills out Kelly’s shoes as Mulligan. Those are fast, muscular, and multitalented shoes to fill. While Kelly could perform equally well as singer, dancer, and actor, Fairchild is a dancer first and foremost, arguably one of the best ballet dancers of our day. His voice, however, is only serviceable as a soloist. The decision to add additional Gershwin songs for him to lead, such as “Fidgety Feet,” was a mistake. Additionally, no one else could ever have Kelly’s megawatt presence, and Fairchild’s theatrical range is limited, even compared to the other actors on stage.

Fortunately the musical is driven by its forceful choreography. For this the production looks much more closely than the film to the history of Parisian modernism. Here Mulligan is something of a Sunday painter until Milo Davenport (Jill Paice) convinces him to work in abstraction. A comical dance within the dance called “The Eclipse of Uranus” gives a nod to dance’s early avant-garde. As the play progresses, the sets also become more abstract, leading to a minimalist pas de deux between Jerry and Lise danced to Gershwin’s eponymous number. In this way the musical pays ultimate tribute to Gershwin’s radical 1928 tone poem. As Gershwin said of his composition, “My purpose here is to portray the impression of an American visitor in Paris as he strolls about the city and listens to various street noises and absorbs the French atmosphere.” Here is a musical that makes it new all over again.