Exhibition view of “Keith A. Smith: The Fabric Works: 1964–1980” at Bruce Silverstein.

THE NEW CRITERION

May 2015

Gallery Chronicle

by James Panero

On “Keith A. Smith: The Fabric Works: 1964–1980” at Bruce Silverstein; “Karen Schwartz: Down the Rabbit Hole” at Life on Mars Gallery; “Mel Bernstine” at McKenzie Fine Art; “Graham Nickson: Spectrum” at Betty Cuningham Gallery; “Louise P. Sloane: Recent Paintings” at Andre Zarre Gallery & “Arts in Bushwick: Making History” at Storefront Ten Eyck

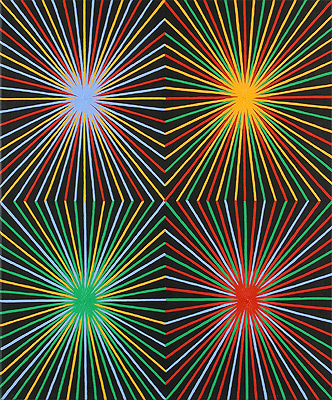

What is a photograph? A book? A collage? A textile? A sculpture? We think we know the answer. Each is a separate medium, with separate training, even separate museum departments. Then we see the work of Keith A. Smith. Art needs no taxonomy. This is certainly true of Smith, a cult artist who might combine photography, collage, and fabric in a single sculptural book, and whose work is now on view at Bruce Silverstein.1

Book Number 28: Stitches (1972) is a perfect example. Here is a book in an edition of one. Smith has made over two hundred such individual books, and few have been shown or seen, although Smith self-published an annotated bibliography (in multiple) as his 200th book in 2000. So why isBook Number 28 even here, in an exhibition dedicated to Smith’s “fabric works”? Because the subject of the book is, in part, the thread that has been ingeniously woven within it, and which moves through holes punched in the pages as you flip through it. “The paper and thread used for binding were also the means of ‘imaging the book,’ ” Smith explains in his bibliography. But that’s not even why it’s called “Stitches”: “The title did not come from the thread which stitched the book and imaged the pages. Rather, making the book and turning the pages kept me in stitches. I was laughing so much from this strange book experience that I had to be careful that tears did not hit the page.”

Born in 1938, Smith studied photography at the Art Institute of Chicago. “When I walked into that school,” explains this son of a seamstress, “I had never been inside a museum before, never heard a symphony, live or a recording.” He moved to Rochester, New York in 1974 to work and teach at the Visual Studies Workshop and never lost his anarchic outsiderness. So he kept drawing connections that others wouldn’t, or couldn’t, such as between the serial quality of multiple camera clicks and the turning of a page, where “Time could be introduced as an element,” or between the shirt on his back and the fabric used to wrap a hard-bound book, or the sheet on his bed and the thread to bind page signatures together. (Smith is now best known for publishing his own book-making manuals. One popular title is Volume I,Non-Adhesive Binding: Books Without Paste or Glue.)

As Smith explains, “the combination of media was only the means to a statement.” His work is personal, esoteric, at times uncomfortably intimate, and deeply tied to his materials. In the current show, the most memorable are his self-portraits printed onto bedsheets, all from the early 1970s. Using the latest in photostatic technology at the time, hoisting himself up and pressing his body in sequence against the platen, Smith used a 3M Color-in-Color machine and later an inferior Color Xerox (after, he explains, Xerox sued 3M over patents) to transfer his body scans to mylar, which he then ironed on to fabric. The nudes resemble the Shroud of Turin. (Smith was, for a time, a seminarian.) A clothed portrait with red socks, a banana peel, and oddly turned-out feet at first looks like a steamroller mishap. Held up, hanging in the breeze, the work shows how Smith infused himself in everyday things, and gave them all great import.

Karen Schwartz, Shadow of His Former Self (2014), Mixed Media Wood Panel and Linen, 72 x 66

The Life on Mars Gallery, in Bushwick’s 56 Bogart Street building, promises to be “about painters and painting” and “painting’s continued relevance in the age of digital media.” Many galleries make such a claim. Michael David, the founder of Life on Mars, delivers on it, putting himself in harm’s way. As a painter who used to exhibit his own encaustic abstractions at Sidney Janis Gallery and Knoedler, David was poisoned by the gases of his own wax medium. His legs remain partially paralyzed by the exposure.

The specter of painting to the extreme reflects on David’s other history, as a bassist for New York punk bands. Most notably this included an early version of the Plasmatics, an extreme act later headlined by the late Wendy O. Williams, a frontwoman known for chain-sawing guitars on stage, blowing up cars, and inviting charges of public indecency. At Life on Mars, David continues to play backup for such female leads, as several expressionistic women have been part of recent group and solo shows, including Katherine Bradford, Joyce Pensato, Amy Sillman, Brenda Goodman, and Fran O’Neill, whose exhibition I wrote about earlier this year.

Now on view at Life on Mars is Karen Schwartz, a painter based in Atlanta and Long Island presenting her first solo New York exhibition.2 I was only able to see the paintings scheduled for this exhibition as they were being prepared to go on view, so I missed the works on paper and Margrit Lewczuk’s abstractions scheduled for the project room.

Schwartz does not back down from a fight. She wrestles with oils and acrylics. Abstract forms turn into human figures only to become effaced. Layers of paint react against resisting agents. Colors drip and run. Scraped-up pigment ends up stuck to surfaces. Shadow of His Former Self (2014) may be the most successful. Here even the painting surface is uneven, with a canvas stuck to a deeper panel of wood. On the left, a ghost-like form fades in the background. On the right, a fleshy nose enters the frame. The psychological weight of Schwartz’s figures can be heavy, at times overbearing, so I appreciate her lighter colors and shots of humor. Another example: Pink Lady (2014), where a scrawl of red lipstick finishes off a figure in a flourish of punk acidity.

Mel Bernstine is another refugee from the downtown New York scene. After studying international relations at Columbia University, Bernstine landed in the intoxicating East Village of the 1980s. More recently he has been drifting across Europe and North Africa, producing some of the most arresting patterned compositions around. While a few examples have made their way stateside, most have only circulated on social media, where, despite their range, they are immediately recognizable for their singular, self-schooled hand.

Now at McKenzie is Bernstine’s solo return to New York.3 Constrained by limited space, Bernstine mainly works small, developing hand-made patterns in acrylic, ink, posca, and pencil that flicker and pulse. The arabesques of Marrakesh mix with the patterns of Optical Art and the rough-hewn feel of East Village diy. At McKenzie all these influences crash together in one four-by-five-foot ink, acrylic, and collage on paper, where a chaos of doodles wraps around hidden names and a 2010 Bonanza Bus Lines ticket from Waterbury, Connecticut. The piece is called A Form of Confusion (2013), and somehow through the confusion the forms make sense.

Over forty years ago, the moment Graham Nickson arrived in Italy to paint as a recipient of the Rome Prize, his car was burglarized of his supplies and preparatory work. With nothing to go on, he climbed on to the roof of the American Academy and began to paint the sunset. Nickson has been painting this way ever since, daring to capture nature’s chroma in watercolor and oil. Now for his first exhibition at Betty Cuningham Gallery, recently relocated from Chelsea to the Lower East Side, twenty-four watercolors of his “experience of coming dawn or falling dusk” are matched with a single, monumental oil on canvas, nine by twelve feet, called Tree of Birds (2014).4 In this latest large work depicting a mountain in Australia, rain clouds blot out the sun. The weather presses down. Birds gather and flap around a tree. As I wrote in 2011, Nickson is “heir apparent to the early American modernists Charles Burchfield and Arthur Dove, with synesthetic work that manages to both radiate and rumble.” This latest painting shows nature guiding his brush with an increasing animistic force. For a painter of the sun, Nickson’s greatest power may be in the shadows.

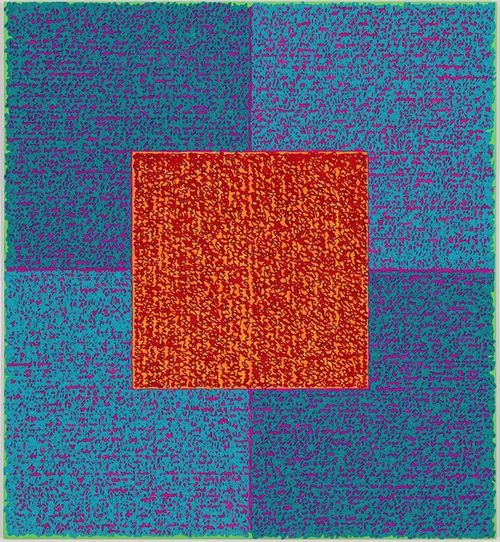

Louise P. Sloane’s recent abstractions are unmistakable. All are squares, divided into quadrants, with another quarter-size square in the center. All are comprised of high-chroma complementary colors. And all are filled with dense lines of what resembles cursive writing, arranged horizontally on the outer squares and vertically on the inner ones. That’s a busy program. Repeated over multiple canvases, it might sound mannered, or overly cautious, with the suggestion that an artist has fallen into doing one thing too well.

Then again, such a series done right can explore the nuances of repetition, pattern, and variation. Such was the case for Josef Albers’s squares, and it is again true for Sloane’s squares now on view at Andre Zarre.5 For these acrylics on aluminum panel, Sloane has become expert at modulating the colors of her squares and her writing. Just the right halo of color radiates around the edges of the compositions and beneath the text. She also contrasts the hard edges of her grid with the hand softness of the writing, which is laid down in three dimensions like pastry piping on top of her grids. Best appreciated in person, the writing shows variation one painting to the next, which have coded titles such as “4cbs” and “Bintel Blues.” What becomes clear is that these are not mechanical repetitions but personal memoirs written out longhand. In fact, her father’s own writing is a source material. Would it be better if this text was more legible, or said something more public (I had to ask if it referenced anything at all)? Perhaps not, as what’s private here gets subsumed into personal abstraction.

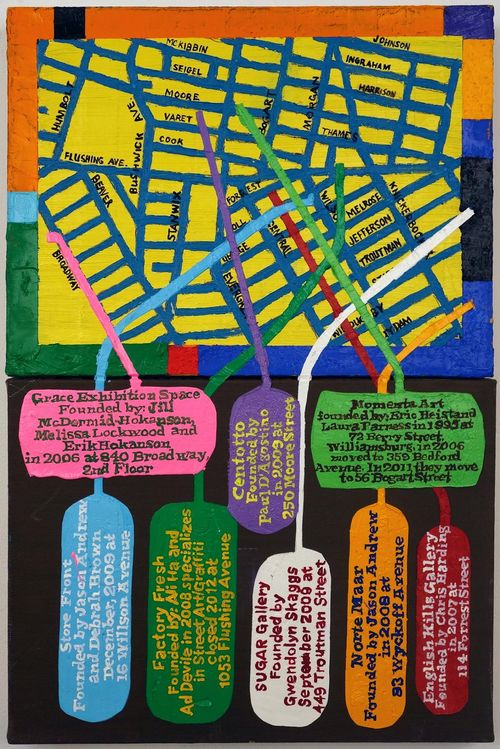

Loren Munk, Map of Bushwick (2009)

A final word, about “Making History”:6 Arts in Bushwick is the all-volunteer nonprofit most well known for channeling the neighborhood’s collaborative energy into Bushwick Open Studios. That sprawling open-door festival, which I wrote about last year, takes place every year during the first weekend in June. Through its own initiative, without celebrity sightings or big-money publicity, bos has earned its place on the art-world calendar. Leading up to Open Studios this year, Arts in Bushwick has organized its first benefit exhibition called “Making History.” The title comes from “History by Exclusion,” an essay by the participating artist Loren Munk. This do-it-yourself manifesto argues for shedding new light on the marginalized “dark matter” of the art world: “Perhaps now we may begin to question what is art, who gets to decide and what’s the artist’s place within society? As self-selected members of the art world it is time we declared, ‘we are our own art history.’ ”

Over four hundred local artists have donated work for the show, which offers an unparalleled survey of the Bushwick scene. The photographer Meryl Meisler and the artist Rico Gatson, both of whose work deals with the inequalities of history, have donated benefit prints. Curated by Krista Saunders Scenna and Dexter Wimberly, the full exhibition remains on view at Storefront Ten Eyck gallery through May 10, at which time all the work will be raffled off at a benefit event. Here the rules are simple: See show. Buy ticket. Win art. Make history.

1 “Keith A. Smith: The Fabric Works: 1964–1980” opened at Bruce Silverstein on April 23 and remains on view through June 6, 2015.

2 “Karen Schwartz: Down the Rabbit Hole” opened at Life on Mars Gallery, Brooklyn, on April 24 and remains on view through May 31, 2015.

3 “Mel Bernstine” opened at McKenzie Fine Art, New York, on March 27 and remains on view through May 3, 2015.

4 “Graham Nickson: Spectrum” opened at Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, on April 11 and remains on view through May 22, 2015.

5 “Louise P. Sloane: Recent Paintings” opened at Andre Zarre Gallery, New York, on April 7 and remains on view through May 9, 2015.

6 “Arts in Bushwick: Making History” opened at Storefront Ten Eyck, Brooklyn, on April 19 and remains on view through May 10, 2015.