THE NEW CRITERION, November 2021

On “Lois Dodd” at Alexandre Gallery, “Marin in the White Mountains” at Menconi + Schoelkopf Fine Art, “John Ferren: From Paris to Springs” at Findlay Galleries, “Frederick J. Brown: The Sound of Color” at Berry Campbell & “Amy Lincoln” at Sperone Westwater.

The fall openings are the temperature check of the New York gallery scene. Despite the ridiculous mandate that arts venues must now demand “vax cards and IDs” at the door—an ordinance that I was happy to see only sporadically enforced—the showing of exhibitions in September and October was alive and well. Just no undocumented arts lovers here, please.

Lois Dodd is one of those artists whose paintings I always look forward to seeing. Dodd finds her subject matter in her domestic surroundings, from her apartment in New York’s East Village to her cottage in Cushing, Maine. With thirty of her paintings ranging from the 1960s through today, an exhibition last month at Alexandre Gallery presented a survey of the nonagenarian’s work in the gallery’s new Lower East Side location.1

From clothes drying on the line to sun-dappled doorways, Dodd looks to the ease of home. But there can be something uneasy in the spare compositions that result. Much of art is about conveying a personal vision, of course, but Dodd’s reveals a strange intimacy. Maybe it was the shift to the gallery’s rougher, new downtown venue, but through their close-cropped glimpses and glances, her paintings seemed oddly private, even unsettling.

Lois Dodd, Sun in Hallway, 1978, Oil on linen, Alexandre Gallery, New York. Photo: Alexandre Gallery.

Take the window-on-window view of Back of Men’s Hotel (from My Window), an opening painting in the exhibition and a recent one from 2016, with its dusky, abstract anonymity. Or My Shadow Painting (2008), another introductory work, of the artist’s silhouette in the grass. While Dodd’s paintings at first seem like still lifes and landscapes, addressing what is seen, they ultimately reveal themselves to be self-portraits, with a vision that captures the seer.

Doors and windows are recurring motifs. These squares and rectangles add visual order and organizational angles to her compositions. They also suggest the division between interior and exterior. In the darkened doorways and obscured windows of Shed Window (2014) and Door, Window, Ruin (1986), the looming thresholds obstruct rather than allow our passage. Where light enters in, such as in Sunlight on Floor + Door (2013), Sun in Hallway (1978), and the doorway of Chicken House (1971), the surrounding shade can have an even greater presence. The arcing shadows of Two Red Drapes and Part of White Sheet (1981) punctuate the angular forms of clothes on the line. Even in an earlier painting such as Six Cows at Lincolnville (1961), the long shadows of the nearby cattle and the distant trees can seem as present in paint as the figures and landscape.

The seasons are similarly observed. In the exhibition, a wall of trees depicting the shifting seasons contrasted the long light of fall with the flat light of winter. Dodd paints the poetry of the everyday through a remarkable economy of form. Her frugal sense for composition is often at its best in winter. In Neighbor’s House in Snow (1979), a white house and landscape dissolve into the white canvas. Meanwhile Steamed Window (1980), the highlight of the show and a remarkable display of division and form, reveals both the cold exterior and the warmth within.

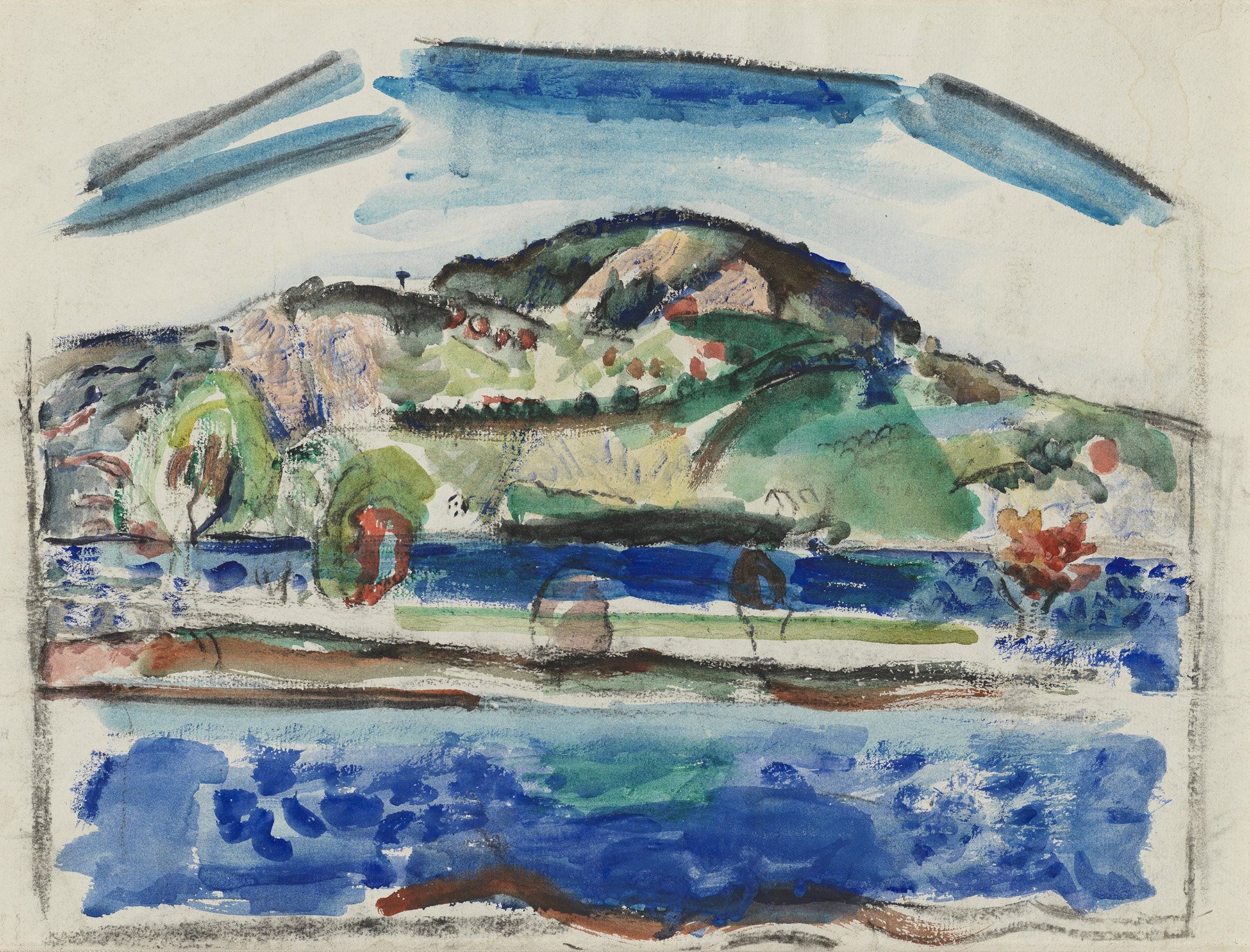

Whether on the coast of Maine or the shores of New York City, John Marin (1870–1953) was at his best in water—depicting port life, which he often rendered in watercolor. Last month at Menconi + Schoelkopf Fine Art, “Marin in the White Mountains” brought together more than a dozen sketches and watercolors from the artist’s lesser-known drawing trips up into the mountains of New Hampshire, which he observed while traveling by car between his two homes.2 Gathered from the artist family’s collection and estate, the works here replaced the skyscrapers of New York harbor and the seascapes of Maine that we usually associate with Marin with those mountains that similarly influenced the Hudson River School painters more than a generation before him.

Filtered through his modernist sensibility, Marin’s watercolors signal their living complexities through wet brushstrokes that seem awash in dew. A series of three plein-air sketches in colored pencil from the 1920s and 1930s that introduced the exhibition also revealed the sense for immediacy that he carried into his watercolors and oils. Like Cézanne, Marin sought to paint the way he sketched, rather than sketch the way he painted, letting observation and action guide his forms.

John Marin, White Mountains, ca. 1924, Watercolor on paper, Menconi + Schoelkopf Fine Art, New York. © Estate of John Marin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Menconi + Schoelkopf Fine Art.

A main room of eight watercolors from the mid-1920s showed how wide-ranging and various these observations and actions could be. The variety of his compositions, while all depicting similar mountains in landscape, demonstrated how Marin did not fall back onto formal idioms, painting the same thing the same way. Instead he let himself stay open and exposed, allowing observation, both of landscape color and of watercolor, to guide his way. At times the results filled the paper, such as in Mt. Chocorua and a-Couple-a-Neighbors (1926). Other watercolors he left more open and spare, for example White Mountain Country, Autumn No. 44, Franconia Range, The Mountain No. 1, (1927), still in Marin’s original red-painted frame, and the wonderfully aqueous White Mountains (ca. 1924). Just beyond the official exhibition, hanging in the gallery’s office, a selection of three oils ranging from 1921 to 1950 showed how Marin even carried these compositional lessons to canvas. Marin could paint his landscapes with as much openness as those small introductory sketches. Like a writer learning on the page, Marin let his art teach him as he remained open to the many possibilities of composition.

John Ferren (1905–70) was one of the original Americans in Paris. “He is the only American painter foreign painters in Paris consider as a painter and whose paintings interest them,” Gertrude Stein gnomically observed. That interest must have gone both ways. Even as he became a member of “The Club” of mid-century New York artists and a neighbor of Willem de Kooning on Long Island, Ferren retained a Continental sense for modernism. “From Paris to Springs,” a survey of Ferren’s work now at Findlay Galleries, follows his development from the late 1920s through the early 1960s.3

Installation view of “John Ferren: From Paris to Springs” at Findlay Galleries. Photo: Findlay Galleries.

Beginning with his Paris-based compositions, Ferren’s paintings were well-studied, well-made, and well-mannered. An early selection of small work reveals his range but also a certain lack of voice. His abstractions echoed the ferment of interwar Paris even as Paris echoed him. These allegiances set up a tension as he returned stateside and his School-of-Paris sensibility ran up against the emerging artists of the New York School. “John, you have betrayed us,” Elaine de Kooning supposedly said to him as Ferren turned to vase-like forms in the 1950s to structure his expressionistic brushwork.

But in fact, Surrealist shapes had always undergirded his abstractions. “Color demands control,” he said, “I was not one of the red-hot brush throwers.” As he turned to larger canvases with a looser, all-over abstraction in the 1960s, Ferren retained his architecture, using squares of color to anchor his brushwork. Through this framed expression, Ferren’s impressive later work prefigures the more controlled post-minimal art of the decades after his death.

“The Sound of Color” was an appropriate title for an exhibition of Frederick J. Brown’s paintings.4 Curated by Lowery Stokes Sims and on view last month at Berry Campbell, the show collected a large selection of Brown’s abstractions from the late 1960s and early 1970s, around the time the young artist first moved from his native Chicago to New York’s SoHo. The foment of this artist enclave included not only painters but also performers, writers, and musicians. Growing up in a musical milieu that included Anthony Braxton and Leroy Jenkins, Brown (1945–2012) followed the music to New York and settled around Ornette Coleman’s loft, where the free-jazz musician performed, lived, and recorded. Now at the center of both experimental music and painting, Brown gravitated to abstraction. He studied the color theory of the nineteenth-century French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul, whose Laws of Simultaneous Color Contrast had influenced the Pointillists. At the same time, he brought to canvas his experiences observing an uncle who was an auto-body repairman and a mother who was a baker. “So I grew up with the tactility and love of paint and color,” he said. “In my mother’s case I was actually able to eat it.”

Frederick J. Brown, In the Beginning, 1971, Oil on canvas, Berry Campbell, New York. Photo: Berry Campbell.

These confluences resulted in bold abstractions of color and variety. Brown spread, splattered, and soaked his compositions. Unusual media such as glitter might appear in the corner, as in one untitled canvas from 1969. Or he might carve a wavy white line into his colorful swirls, as in another numinous canvas from 1977. In the Beginning (1971), the largest painting in the show, is a powerhouse of amplified visual energy.

Brown was an even more independent artist than this survey suggested. One abstraction from 1974, Second Time on the Wall, introduces wild chalkboard-like doodles and calculations onto a soaked abstract background. Brown’s work from later in the decade thickened with such rebus-like components. In the 1980s, he turned to figuration, painting a suite of portraits of jazz musicians and his mentor Willem de Kooning, for which he is best known. This focused survey, the first at the gallery of the artist’s estate, calls out for further examinations of this varied body of work.

Amy Lincoln can be a master of gradation. Her paintings are well-wrought studies in stepped color and tone. At Sperone Westwater, in her first exhibition at the Bowery gallery, she made the most of her gradations through uncanny acrylic compositions that took deliberate steps across the spectrum.5

Amy Lincoln, Storm Clouds with Lightening, 2021, Acrylic on panel, Sperone Westwater, New York. Photo: Sperone Westwater.

Moving beyond the vegetative still lifes of earlier work, Lincoln conjures up tableaux of sun and waves, moon and stars. The ordered arrangements and moonbeam kitsch have a naive aura, with a fun, knowing new-ageness that can be haunting and strange. Sometimes these paintings seemed overly repetitive and flat, trapped in some screensaver afterglow. The best were the ones where Lincoln’s acute sense for shade and depth allowed her compositions to live and breathe. The claw-like waves of Storm Clouds with Lightning (2021), reaching up to a jagged bolt and raining cumulus, were a tour-de-force, suggesting a narrative power both within and beyond the color wheel.

1“Lois Dodd” was on view at Alexandre Gallery, New York, from September 9 through October 23, 2021.

2 “Marin in the White Mountains” was on view at Menconi + Schoelkopf, New York, from September 13 through October 15, 2021.

3 “John Ferren: From Paris to Springs” opened at Findlay Galleries, New York, on October 4 and remains on view through November 12, 2021.

4 “Frederick J. Brown: The Sound of Color” was on view at Berry Campbell, New York, from September 9 through October 9, 2021.

5 “Amy Lincoln” was on view at Sperone Westwater, New York, from September 9 through October 30, 2021.