THE NEW CRITERION, December 2021

On Alexandre Lenoir and the Musée des Monuments Français.

Just off the rue Bonaparte, in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés district of Paris, in the courtyard of what is now the École des Beaux-Arts, is a fragment of a fragment. Here on a sliver of wall is a historical remnant that might be easily overlooked: a Renaissance façade attached to what is now known as the chapel building. The wall did not originate here. What we see instead—rather surprisingly—is a slice of the Château d’Anet, Philibert de l’Orme’s sixteenth-century castle built for Diane de Poitiers, the mistress of Henry II. Over two centuries ago, this façade was brought by boat from the Loire Valley to this corner of the Left Bank, piece by piece, to save it from destruction. Salvaged and restored, the ornate assembly of columns and statues then served as the entrance to the Musée des Monuments Français—the Museum of French Monuments. Today this façade remains one of the few pieces of evidence of a museum that rescued numerous such objects of French history and defined, in fact, what it means to be a museum. The façade also serves as a tribute to Alexandre Lenoir, the director of this museum who defied the Reign of Terror with his institution. Quite literally at times, Lenoir was all that stood between art and revolution.

Jacques-Louis David, Alexandre Lenoir, 1817, Oil on wood, Louvre, Paris. Photo: © 1988 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre).

The Louvre Museum, that encyclopedic creation of the French Revolution, founded in 1793 and just a five-minute walk from here across the Seine, has long captured the world’s attention. Yet it was the Museum of French Monuments, officially founded two years later but already in formation at the height of the Terror thanks to Lenoir’s interventions, that was far more central to the salvation of French history and its artifacts during the most destructive moments of revolutionary fervor.

The relative silence around the story of Lenoir speaks to history’s long valoration of the French Revolution and the suppression of its most disturbing moments. While Lenoir understood the language of the revolution, his museum stood as a last defense against some of its most radical acts of vandalism and desecration. “No account of the dawn of the museum age in France would be complete without it,” Andrew McClellan said of the Museum of French Monuments in his own history of the Louvre. Nevertheless, as Christopher M. Greene noted in his study of Lenoir from 1981, “Lenoir and his museum have received little serious attention from students of history or the arts, though these students have sometimes referred to them in passing, often in tones of disparagement.” A dissertation by Alexandra Stara, published by Routledge in 2013 as The Museum of French Monuments 1795–1816, was the first full scholarly treatment of Lenoir since the 1880s. For those who trumpet total revolution, the history of a figure who stood against the Reign of Terror is best left forgotten.

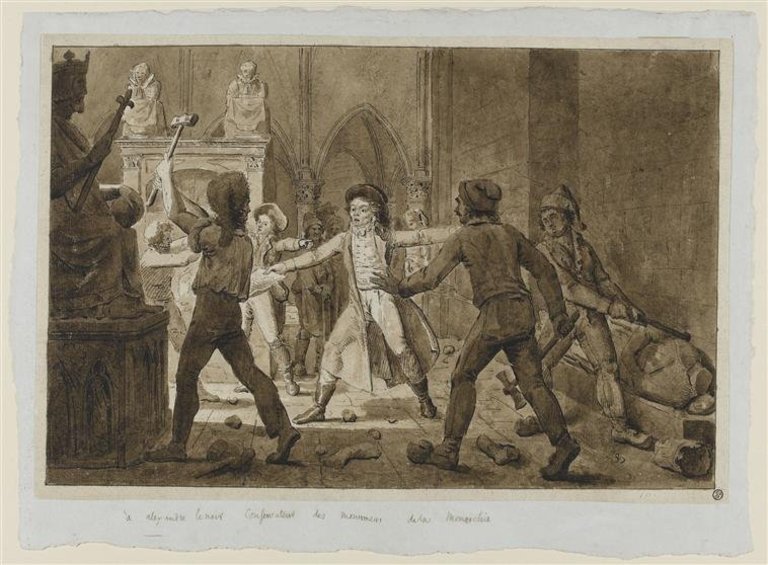

In the summer of 2020, the controversy that can still surround Lenoir was made all too apparent. A year ago in these pages, we had occasion to reflect on the curator Keith Christiansen, then the chairman of European Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who made the mistake of bringing up Lenoir during our own season of vandalism and desecration (see Notes & Comments and “Unmaking the Met,” December 2020). “Alexandre Lenoir battling the revolutionary zealots bent on destroying the royal tombs in Saint Denis,” Christiansen wrote on social media, posting a print of the French curator with arms outstretched against the sledgehammers. In 2020 as in 1789, Lenoir showed how a museum can be a sanctuary for art and artifacts in an age of destruction. “The losses that occur” when major works of art are destroyed by “war, iconoclasm, revolution, and intolerance,” Christiansen explained, are the enemies of art history, diminishing our “fuller understanding of a complicated and sometimes ugly past.” He then wondered: “How many great works of art have been lost to the desire to rid ourselves of a past of which we don’t approve. How grateful we are to people like Lenoir who realized that their value—both artistic and historical—extended beyond a defining moment of social and political upheaval and change.”

Artist unknown, Alexandre Lenoir defends the monuments from the fury of the Terrorists, Eighteenth century, Drawing, Louvre, Paris. Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre)/Thierry Le Mage.

How grateful, indeed—and how inappropriate, it was quickly determined by our latter-day tribunes, for this curator to suggest such a connection between that summer’s reign of terror and the Reign of Terror. The uproar over Christiansen’s statements—“shared on Juneteenth,” as The New York Times reminded us—made national headlines. Museum leaders had him remove the post and delete his private Instagram account. As he was led up to the social-media guillotine, Christiansen finally recanted: “I will make no excuses except to say that I had in mind one thing and lacked the awareness to self-reflect on how my post could go in a very different direction, on a very important day . . . and would cause further hurt to those experiencing so much pain right now,” he wrote. “I want to be clear on my view that monuments of those who promoted racist ideologies and systems should never be glorified or in a location where they can cause further harm.” Met leaders then apologized for their institution as being “connected with a logic of what is defined as white supremacy” while announcing plans for Christiansen’s retirement.

Christiansen was right to consider the parallels between the French Revolution and our own Jacobin times, and for this he was denounced, appropriately enough, by our present-day Robespierres. He also did a service by reminding us of Lenoir’s role in countering revolution’s most destructive energies. The best minds of the French Revolution—the ultimate product of the Enlightenment, after all—organized committee after committee and issued decree after decree to control a revolution that proved uncontrollable. Against these many pronouncements, Lenoir understood that the future of France depended on preserving the objects of its past. His institution revealed how the public museum—a new invention—could have a central role not only in collecting works of art but also in preserving the artifacts and monuments of cultural patrimony.

The Museum of French Monuments began its existence as a revolutionary depot for materials seized from the Church and, soon after, the monarchy. On November 2, 1789, the Revolutionary Assembly nationalized Church property. Bronze statues were melted down into guns and cannons. The lead from church roofs was stripped away and turned into bullets. Books and manuscripts were shredded to make cartridges. The revolutionaries seized so much loot that it could not be sold off quickly enough, even as raw materials. On October 15, 1790, the Committee for the Alienation of National Assets decreed that two new depots were to serve as warehouses where cultural detritus could be carted away and centralized. Along with the Hôtel de Nesle, the suppressed convent of the Petits-Augustins, with its campus of courtyards and buildings with canal access to the Seine, was set aside to serve as a convenient warehouse for the revolutionary haul.

Born in Paris in 1761, raised by a clergyman uncle in Alsace outside of the capital’s academic circles, Lenoir was a court painter who found himself at just the right place and right time to stand against the worst insults of the revolutionaries. An apprentice to the royal artist Gabriel François Doyen, Lenoir stepped into the role of guardian of the Petits-Augustins when Doyen took up an invitation from Catherine the Great and decided, quite wisely, to settle in Saint Petersburg. One of his final acts in France was to recommend his student of fifteen years for the position.

Lenoir proved to be remarkably adept at staying afloat through the rising tides of revolution. He argued, for example, that church statues should be saved for what their garments might teach us about the history of costume. Since the revolutionaries coveted metal for its raw material, and bronze sculpture was particularly vulnerable to seizure and destruction, Lenoir painted over bronzes by Jacques Sarrazin to disguise them as marble. He was also a smart negotiator in an era that could give and take more than just works of art. He once arranged for the return of a bronze from the foundry; the paintings that were seized in exchange were burned on a revolutionary pyre in one of its orgiastic festivals.

From an album of Alexandre Lenoir and Charles Percier, Heads of the kings of France, Date unknown, Drawing, Louvre, Paris. Photo: © RMN.

The execution of Louis XVI on January 21, 1793, brought about the nationalization of royal property and accelerated the bloodshed of the revolution. On July 4 of that year, the National Convention decreed that the symbols of the ancien régime were to be destroyed within days. It set its sights on the royal tombs in the abbey church of Saint-Denis just north of Paris. In August the Convention organized the ritualistic desecration of the tombs in an event over several days that saw some of the worst vandalism of the revolution. Saint-Denis was renamed Franciade as revolutionaries attack its royal monuments with hammers, using the rubble to create a grotto for a festival in honor of Marat and Le Peletier. They then exhumed the remains from the tombs and began piling the corpses in front of the cathedral. The bodies of some forty-six French kings, along with the remains of over a hundred other nobles, were pulled from their graves.

The Convention called this revolutionary act the “Last Judgment of Kings.” The revolutionaries went for the bones and ash of the oldest kings—the Merovingians, the Carolingians, and the Robertians—and moved on to the newer and more odoriferous remains of the houses of Valois and Bourbon. As more bodies were exhumed, a black vapor began to envelop and sicken the revolutionaries.

At two hundred years old, the remains of Henry IV, the “good king,” then surprised the mob by the unsullied state of his preservation, which they took as an omen. For a time the revolutionaries propped up his body as an attraction, clipping his hair and beard and pulling his teeth as souvenirs. A woman then came into the cathedral and cursed him before punching his corpse in the face, sending him tumbling to the ground. Like his royal relatives, the good king ended up in a trench covered in lime next to his mother-in-law, Catherine de’ Medici. The status of Henry’s head, however, remains a point of contention. Decapitated like those of the other monarchs, the head recently made headlines, so to speak, when it was discovered in a Parisian attic and forensically linked to le bon roi.

From an album of Alexandre Lenoir and Charles Percier, The body of Henry IV exhumed from his grave in 1793, 1793, Drawing, Louvre, Paris. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais/Photo F. Raux.

An eyewitness to these revolutionary acts, Lenoir took detailed notes of the destruction. Using his artistic skills, he made field sketches of the royal corpses before they were deposited in the communal pits. He successfully thwarted the destruction of the tombs of Francis I, Henry II, Charles VI, and Louis XII, and began transporting the salvaged stones to the Petits-Augustins. He also gathered his own samples of royal remains—the scapula of King Hugh Capet, the femur of Charles V, the tibia of Charles VI, the vertebrae of Charles VII, the ribs of Philip IV and Louis XII, the lower jaw of Catherine de’ Medici, the tibia of Cardinal de Retz—this time not only as revolutionary souvenirs but also as relics to be re-interred on the grounds of his museum. Over two centuries on, a print of Lenoir defending these Saint-Denis tombs is the one that Keith Christiansen was compelled to suppress.

After the execution of Robespierre and the Thermidorian reforms of July 1794, Lenoir, inspired by the tombs he saw at Saint-Denis, set about turning his depot of salvaged works into a museum for the new republic. That same year, Henri Grégoire coined the term “vandalism” to decry the waves of destruction, aligning the revolutionaries with the tribe of Vandals that sacked Rome and destroyed its monuments in 455 A.D.

Using the language of revolution to stand against revolution, Lenoir wrote to the Committee of Public Instruction and the Temporary Arts Commission. He said he would like the Petits-Augustins to become a permanent repository for the “masterpieces which used to decorate the temples of the fanatics, the palaces of the tyrants and the houses of their affiliates.” On October 21, 1795, the Committee declared the Petits-Augustins to be a permanent space for Lenoir’s exhibition of French monuments.

Jean Lubin Vauzelle, Vue du Musée des Monuments Français, 1816, Drawing, Louvre, Paris. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais /T. Ollivier.

In addition to the tombs of Saint-Denis, Lenoir had saved such artifacts as the mausoleum of Richelieu from the Sorbonne chapel, Tintoretto’s painting of the Deluge, and monuments from the monasteries of the Célestins, the Grands-Augustins, the Minimes, the Feuillants Saint-Honoré, and the Petits-Pères, as well as fragments from the churches of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Saint-André-des-Arts, Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes, Sainte-Geneviève, and Notre-Dame. In some cases he purchased tombs that would have otherwise been sold for the price of their raw materials. In others Lenoir placed himself directly in harm’s way. He was wounded in the hand as he stood against riotous soldiers sacking the chapel of the Sorbonne, saving the monument if not the body of Richelieu himself. While Lenoir managed to get the tomb back to the Petits-Augustins, soldiers decapitated Cardinal Richelieu’s corpse and displayed his severed head on a pike for the amusement of the crowds.

As with Girardon’s marble Descent from the Cross from Saint-Landry, which arrived in a hundred pieces, Lenoir then set about the complex process of restoring these many fragments. In some cases he created his own fabrications—fabriques—made up of a combination of salvaged artifacts to serve as new monuments and tombs for the cultural remains that came his way. With columns from the church of the Minimes, he crafted a new tomb for Descartes. He also created monuments for the remains of Turenne, Molière, La Fontaine, Pascal, Racine, and Héloïse and Abélard, the famous twelfth-century lovers. Some of these monuments he placed inside the church and cloisters behind his salvaged façade from the Château d’Anet. For others, he created a new cemetery in the nuns’ garden just behind the former convent buildings, which he called his Elysium. He planted his jardin Élysée with pines, cypresses, and poplars and fronted its gate with a freestanding façade saved from the Château de Gaillon.

The Museum of French Monuments was a new museum of singularly old parts. Beyond the Anet gate, a long initial gallery gathered some of the best pieces of the collection together across time and space. This assembly included a Roman altar to Jupiter, which had been found under Notre-Dame, a statue of King Clovis and Queen Clotilde, a tribute to Queen Blanche, and a relief depicting the miracle of Saint Philip. Subsequent rooms then tracked the evolution of French style through the centuries from the thirteenth to the eighteenth.

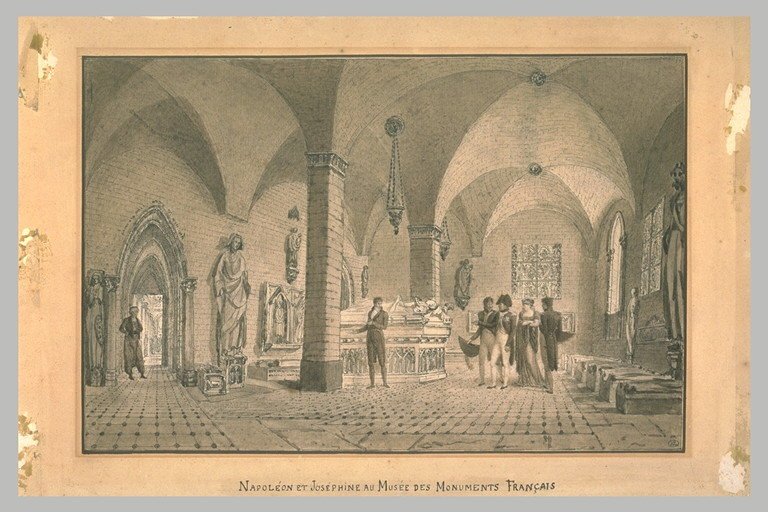

As he wrote to the Committee of Public Instruction, Lenoir believed this new collection would encourage his visitors to cry out, “How fortunate am I to be born French!” It might have sounded like a hollow wish after such turmoil, but Lenoir saw the nascent spirit of nationalism in his objects of French patrimony. As revolutionary fever gave way to the Napoleonic imperium, his new museum became widely popular in France and an international attraction to visitors up until its shuttering in 1816. In December 1800, Napoleon and Josephine made an approving visit, and Josephine herself became a key supporter of Lenoir.

Artist unknown, Napoleon and Josephine visit the Museum of French Monuments, Nineteenth century, Drawing, Louvre, Paris. Photo: Louvre.

Sir John Soane and Wilhelm von Humboldt, two early museum founders, both visited and took inspiration. The Humboldtian Royal Museum in Berlin, now the Altes, opened in Berlin in 1830; Sir John Soane’s Museum opened to the public in London in 1837. We can also spot the legacy of Lenoir in New York’s Cloisters, John D. Rockefeller, Jr.’s 1938 composite of religious fragments arranged in ecclesiastical pastiche, again made possible in part through the diaspora of materials from France’s religious buildings.

Lenoir did more than inspire new museums. He gave pride of place to the past when others only looked to the future. At a moment when revolutionaries were desecrating corpses, he found a way to honor the dead in his Elysium. He emphasized the lives of the personalities on display and sought to inspire a “sweet melancholy that would speak to sensitive souls.” Lenoir formed his museum for France’s medieval, Renaissance, and baroque history when neoclassicism was the only order of the day, especially among the revolutionaries. France’s Gothic heritage was so worthless at the time of the revolution that those artifacts unfit for ritual burning or desecration were simply sold off by the pound—or rather, by the kilogram—to be quarried. “Very few men of the time valued the things that he prized,” writes Christopher M. Greene in his study, “and it was one of the main purposes of his museum to educate his contemporaries.”

Lenoir’s role in reviving interest in the Gothic later in the nineteenth century cannot be overstated. Alexandre du Sommerard took direct inspiration from Lenoir for his Musée de Cluny, which opened after his death in 1843. So did Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, whose own Musée national des Monuments Français opened in 1882. Like many observers, the nineteenth-century French historian Jules Michelet recalled his childhood visits “under those somber vaults to contemplate those pale faces, curiously, ardently searching from hall to hall, century to century. What was I seeking? The life of days gone by, no doubt, and the spirit of the ages.”

It might be said that the Museum of French Monuments became a victim of its own success. Following the Hundred Days and the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, Lenoir’s museum seemed, at least to some, to serve as an unwanted reminder of revolution, even though it did more than any other institution to protect French artifacts against the revolution. The year 1816 quickly saw the disbursement of Lenoir’s artifacts. Some of Lenoir’s monuments were relocated to the new cemetery of Père Lachaise, which had opened in 1804. The transfer of the famous figures of French literary history, from La Fontaine and Molière to Héloïse and Abélard, gave Père Lachaise its star attractions. Lenoir’s fabriques provided the cemetery with its visual appeal and can still be found there today. Meanwhile, eighty-four pieces of Lenoir’s collection went off to create a new Gothic gallery at the Louvre. Other items formed a new national museum at Versailles. Lenoir’s museum was then given over and rebuilt as the new home of the École des Beaux-Arts. Finally, the restored monarchy saw to the restoration of the royal tombs of Saint-Denis. The administrator tapped to oversee their return and preservation in the royal church was Lenoir himself.

Even though his museum came to an end, Lenoir continues to influence our appreciation of history in the modern age. “It seems,” wrote one observer in the journal Semaines critiques, that Lenoir’s “powerful hand holds back the centuries on the edge of the abyss, draws them up each in its proper place, and forbids them to expire, in order to display their arts, their great men, their tyrants, and often their ignorance.” Or as the nineteenth-century French historian Baron de Guilhermy wrote, the

aspect of that collection produced a profound effect on artists and the public. People began to deplore the ruin of so many masterpieces, and soon there was a cry of reprobation against the stupid fury of the iconoclasts of 1793. It was certainly from that time that one can date, in our country, the era of the rehabilitation of the art of the middle ages.

In ages of upheaval, the story of Lenoir calls out for its own rehabilitation.