Peter Reginato, Drunken Angel, courtesy of the artist

THE NEW CRITERION

April 2011

Gallery chronicle

by James Panero

On “Peter Reginato: Polychrome” at Heidi Cho Gallery, “Mel Kendrick: Works from 1995 to Now” at David Nolan Gallery & “Thornton Willis” at Elizabeth Harris Gallery.

Sculpture has a weight problem, and the laws of nature are rarely kind. Gravity never gives up trying to tug matter to the ground. How sculptors confront this force often determines the power of their work. Sometimes sculptors play up the heftiness. The minimalist Richard Serra built his career around work that menaces viewers with teetering sheets of metal. More often, sculptors aim to overcome gravity’s pull. Rather than pressing down, their work reaches up, with an energy that seems greater than the scale and materials might allow. Occasionally, sculptures soar without leaving the ground.

The sculptor Peter Reginato came to his practice by way of the hot rod, that energized American demotic craft. Born in Dallas, Texas in 1945, Reginato grew up outside Oakland, California in the heart of postwar car culture. He moved to New York in the mid-1960s, around the time he started making abstract sculpture. He never forgot the lessons of the Kustom Kar Kommandos, to borrow the title of Kenneth Anger’s 1965 cult film. Speed and invention, with a flash of machismo, became his hallmarks.

Starting out, Reginato dabbled in primary structures—another minimalist crystallizing the avant-garde into a weighty fortress of solitude. Yet he soon broke ranks, developing ever more whimsical, maximal composites of surrealistic planes, flattened metal sheets cut into amoebic shapes, fastened together, and painted in a riot of colors. Today he continues to work in the auto-body style of welded steel, a pyrotechnician with a helmet and a blow-torch building explosions in space, loud and indecorous, often with suggestions of leaves and figures, and titles like “Funk Happens."

In 2009 Reginato exhibited an iteration of his work at the Heidi Cho Gallery in Chelsea that was something of a breakthrough, a clearing out of the body shop and the start of something new. Here, instead of building works out of an assembly of steel planes, he “drew” the outlines of his recurring shapes with metal poles, polished rather than painted to a shine. The result lightened the load of the sculptures to a cloud-like state, with shapes now formed out of the negative space between the metal.

The work did more than shed pounds. It also took on a new energy in the way the eye ran over it. Rather than zero-in on the center of the cut forms, the eye observes the lines around it, following the bends and curves of the rods. The effect reminded me of Gjon Mili’s famous 1949 photographs of Picasso in his studio working with a “light pencil,” where he traces the outline of figures with a flashlight in the space between him and the camera, a process captured through the extended exposure of the film. In both cases, the eye looks over the long line from start to finish.

Since 2009 Reginato has been adding to his open forms, customizing and tricking out the factory models. Now again at Heidi Cho, we can see the conclusion, or rather the latest stopover, of the process.

Back is the color, lending this show its title of “Polychrome.” As in that Picasso picture, Reginato draws and paints in space, here captured in steel rather than photographic emulsion. An artist friend suggested that color makes Reginato’s work unmistakable. I agree. Even more than form, color is his signature. He shares a sensibility for the handling of color with his peers of the 1970s loft generation. Gestural brushwork humanizes the coldness of the steel. It’s not surprising that Ronnie Landfield, the great lyrical abstractionist, has been a friend of Reginato’s since his California days.

In the sculptures now at Heidi Cho, several of them more figure-like than usual, the blended colors appear like the lights reflecting off a figure on a stage, bright and flashy, and sometimes campy and garish. In each sculpture, Reginato starts with an assembly of planes cut in whimsical shapes, much like his older work, but then adds the rods of bent metal. Hip Shaken Mama (2010) comes on like a 1 a.m. set performer out to grab attention at all costs. The piece also serves as a case study in the rhythm that Reginato can attach to form, with each part suggesting a different sort of movement. The zig-zag of a narrow strip of body is a tight jitter. The curve at the waist is more a sashay. The rounded bumps of the left leg is a toe tap. The curving metal poles of the right leg and arm are limbs circling around so quickly we detect the movements more than the forms.

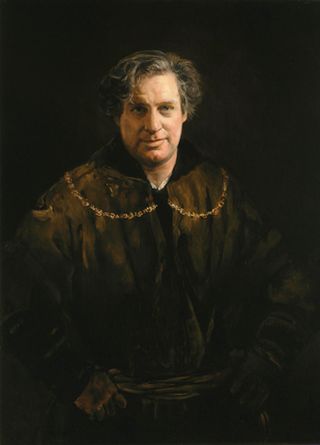

The larger Drunken Angel (2010) steals the show. The work is almost all bent tube, and there’s a mess of it. Rather than merely outlining shape, the rods here trace out movement. The lower half never quite comes together. Too much armature gets used up in a base that seems needlessly clunky. The upper half is a different story. The wings of the figure are spiraling, circulating curves of wire. Just below is another vortex of wire, the air spinning beneath. The figure appears to arch back at the shoulders, chest out. An additional pole curves off the head and back down to the floor, a final flourish that I found distracting up close, if not a little dangerous. Once I backed away it made more sense. I no longer bothered to wonder about each strange, expressive part. After all, it’s unwise to question an angel too much, especially at liftoff, especially one that’s drunk.

Mel Kendrick is a sculptor of process, but his product was the big hit two years ago in Madison Square Park in Manhattan. In the center oval, the park conservancy temporarily installed five enormous new works, all of the same series called “Markers.” The forms were unmistakable Kendrick, shapes he had been working on in wood for several years.

A number of these, in much smaller scale, went on view at David Nolan’s former Soho gallery space in 2007. Each began with a cube of wood, which Kendrick cut and cored. Through this process, he extracted an internal section, a constructivist folly of interlocking cylinders. He left the outer cube intact enough to stay square. Kendrick then placed the core on top of the cube, a weighty figure held up on a hollow base of its former self. The pieces had strict internal logic, but I found them a little smug. They were more process than product, slightly too satisfied in their own art smarts.

For the park, Kendrick enlarged these shapes to over ten feet tall. The cube base became human-sized, like a sliced and diced version of Tony Smith’s six-foot Die. Kendrick also enlivened his surface by creating the work out of alternating layers of black and white poured concrete, like a modernist fantasy of thirteenth-century Siena. With this surface treatment, the works took on a new sense of play. But the real play came after installation. Throughout the run, kids were all over them. They crawled through the carved-up bases and peeked through the holes. They moved through the work the same ways our adult eyes looked it over—usually from a little more distance.

Now at David Nolan’s Chelsea space, a survey of earlier works reveals how Kendrick arrived at his monumental park accomplishment. Much like the excellent arte povera artist Giuseppe Penone, Kendrick has a feel for the logic of wood. In Plug and Shell (2000), he carved up a section of tree trunk, here following the wood grain of the limbs and preserving the vestigial stumps. Rather than stacking the results, he positioned the two parts side by side, the denuded wood on the left and its knobbly bark to the right. He also placed them on alternating bases, one built of stacked cinder-blocks, the other of four metal poles—one solid, the other hollow.

Other pieces have a similar binary relationship, with Kendrick working through different finishes and the question of how precisely to connect the two parts. The two sides of Plug (2000) are both stained black, with the shape of the core now less connected to the wood grain of its shell. In BDF (1995), the two parts are identical forms of assembled sticks, one a rubber cast of the other.

I found the towering Black Trunk (1995), the largest work in the show, to be the most compelling. Here Kendrick took a nearly ten-foot section of large tree, sliced it in smaller pieces, and carved out the center. He then restacked the now hollow tree and carved out a series of dovetail joints. Left open, the joints afforded keyhole glimpses of the interior. They also hinted at a sense of instability, as if someone last minute forgot a very important structural component and a bump could send it toppling over. Yet despite the theater of its display, the dominant feeling was one of arboreal mystery. The sculpture felt like an old-growth giant somewhere deep in the woods. I liked its expressiveness. A large rubbing of the trunk that Kendrick made on paper, displayed on the gallery wall beside it, maintained the binary logic of the show. It also spoke to the more poetic desire to preserve a record of the tree, something to take back out of the forest.

The painter Thornton Willis is a friend. I mention that less in the interest of full disclosure and more just for bragging rights. Willis is the embodiment of true painterly feel—a feel that is actually felt. In his hands the School of Hofmann gets schooled in old-time religion and the healing touch of the primitive South, where Willis was born to an itinerant minister’s family in Pensacola in 1936. An evangelical for American abstraction, Willis is now working at his creative peak, quite an accomplishment for an artist who has been producing significant paintings since the 1960s.

One of the qualities I admire in Willis is his ability to change. When other artists would turn on the auto-pilot, he moves on to a new idiom. A few years ago it was prismatic triangles. Then in 2009 he left that for the lattice. His bright colors and dexterous paint-handling created an undulating sea of shallows and deeps, with parts coming forward and others receding in an energized surface. I contributed the catalogue essay for that exhibition.

Now at Elizabeth Harris Gallery for his third solo show there since 2006, Willis is on to his latest “primal, visionary, even shamanistic” accomplishment, as Lance Esplund writes in the catalogue essay. A painter in the city, Willis translates the skyline into a Tetris-like puzzle, giving us cosmopolitan titles like Gotham Towers (2009) and Streetwise (2010). Yet as in his Homage to Mondrian (2009), Willis is more interested in the boogie-woogie of Broadway than in the literal streetscape.

Given the relative complexity of these recent shapes compared to the simpler squares and screens of the lattice series, the paintings with the most saturated, solid forms were the most successful. The more dissolving brushwork that made his earlier work so compelling couldn’t quite hold these newest shapes together. Juggernaut (2010) was therefore the standout. Not only were the shapes rich in color, but Willis also separated them with heavy black lines. For all the talk of color, Willis knows his black. Rather than lock things down, these heavy lines gave the work its lift, as if forming shadows cast by the colorful shapes, rooftops in the twilight of a summer afternoon. Out of a puzzle of interlocking planes, suddenly there was a mountainscape of the city’s vitality inviting us up and up and up.