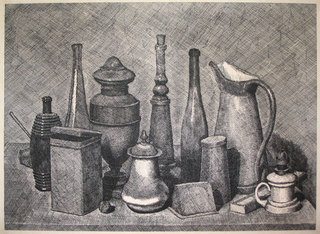

Giorgio Morandi, Grande natura morta con la lampada a destra, 1928, etching

THE NEW CRITERION

OCTOBER 2008

Gallery chronicle

by James Panero

On "The Etchings of Giorgio Morandi" at Pace Master Prints, New York, and "Giorgio Morandi: Paintings and Works on Paper" at Lucas Schoormans Gallery, New York.

For thirty years, the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Philippe de Montebello, has been a model of sobriety in a decadent age. Other institutions have succumbed to the fashions of the moment, but the Metropolitan has remained a museum of art. Great art and excellent curators have been championed over financial and egotistical concerns. And while de Montebello’s leadership has been rooted in the best traditions of conservatorship, it has also been visionary. The good works of his museum radiate out into the culture at large. The story in the galleries this month certainly bears that out.

I don’t put much stock in the forwards to museum catalogues, usually a boilerplate of acknowledgments. But de Montebello’s essay for the Met’s Giorgio Morandi retrospective, reviewed in this issue by Karen Wilkin, is revealing. “Like his paintings,” writes de Montebello, “small in scale and intimate in content, Morandi never fit into the declamatory, self-aggrandizing mode of the most prominent twentieth-century masters. He was a quiet, almost reclusive, and deeply thoughtful man, content to explore his own artistic preoccupations without concern for the expectations of the fast-paced world of artistic fashion.”

These statements could have been a manifesto for de Montebello’s leadership over the last three decades—an attitude that, outside of the Metropolitan, has given license for the New York art world to look beyond the “fast-paced world of artis- tic fashion” and to appreciate slower rewards. “It is indeed unusual to see twenty-seven of Giorgio Morandi’s etchings in a New York gallery,” writes the painter and curator Janet Abramowicz in her essay this month for “The Etchings of Giorgio Morandi” at Pace Master Prints.[1] How right she is. I doubt that even a top-flight gallery like Pace could have considered mounting a sizable exhibition of Morandi’s intimate etchings without the institutional legit- imation provided by the Metropolitan Museum.

Abramowicz studied printmaking with Morandi at Bologna’s Accademia di Belle Arti and went on to become his teaching assistant. She has written the essay on Morandi’s etchings for the Metropolitan catalogue and acted as curator for the Pace show, assembling work from six American collections and from the Museum of Modern Art. The result is an education in Morandi’s development as an etcher, here displayed chronologically in work ranging from 1921 to 1961.

“Etching was an integral part of Giorgio Morandi’s oeuvre,” Abramowicz notes in her Metropolitan essay. “Rather than simply being a complement to his painting,” certain images, Morandi believed, “could be expressed in this medium only.” Yet as Abramowicz writes for Pace, “traditional etching was the medium least conducive to the tonalities Morandi sought in his oeuvre, and it is a tribute to him that he mastered one of the most trying of traditional techniques.”

Morandi’s artistic development was very much defined by his evolution as an etcher. In 1912, as a student, Morandi dropped out of the Accademia for a year in order to teach himself the printmaking process. In doing so he revealed his passion to be more traditional than even his academic minders—he wanted to learn the hard-ground technique of Rembrandt—but he also wanted to apply etching to his modernist vision.

It took Morandi six years to feel comfortable with etching, a process that relies on a volatile chemistry of acid baths to open up or “bite” the furrows in the metal printing plate carved out by the etching needle. You might say it took Morandi a lifetime to test etching’s potential, learning how to adapt a lineal art, an art based on line, to reflect his interest in tone. Il ponte sul Savena a Bologna (Bridge on the Savena River at Bologna, 1912), a landscape and the earliest work in the show, already reveals Morandi’s reserved sense of composition but not yet the assuredness of his etching needle. His marks are a loose thicket of hatchings, his lines doggedly tracing out the architecture of the landscape—the curve of the road, the arch of the bridge. The hatchwork of shadow lines mingles and loses itself in the tonal shading of the trees and rooflines. Compare this to Natura morta con bottiglie e brocca (Still Life with Bottles and Pitcher, 1915), a futurist still life where the tonal areas already feel more assured and light-handed. Rather than merely containing shadow lines, the volumes here are defined by the etching hatchwork.

Morandi’s breakthrough comes in 1921 with the tiny Pane e limone (Bread and Lemon), just one-and-a-half by three inches, which, for Abramowicz, calls to mind Rembrandt’s Small Gray Landscape. Here the background and surrounding area get equal, if not more, attention from the etcher’s needle than does the subject matter itself. The hatch marks have an all-over effect. Morandi defines his objects entirely through their tone, using a texture of lines woven like linen, reflecting the weave of the printed paper, to darken the areas around and beneath the lemon and bread. In Veduta della Montagnola di Bologna (View of the Montagnola in Bologna, 1932), these textures become more abstracted, largely uniform fields of pattern—a dense but even hatchwork of diagonal, vertical, and horizontal lines for a field in shadow, a more open pattern for areas in sun.

The remaining work in the Pace show displays Morandi’s application of his all-over hatching for his iconic still lifes of bottles and other household objects. The blissful regularity of his ordinary subject matter is probably Morandi’s most radical contribution to modernism and still his most debated accomplishment. Through repetition, Morandi was able to revisit the same objects with an experimental eye, changing his approach each time and turning his etching technique into a subject matter of its own. His work becomes more interesting the more he dissolves the plastic shapes of his bottles and cans into the patterns of the etching line. I prefer the wavy Natura morta a grandi segni (Still Life with Large Signs, 1931) to the more “realistic” rendering of Grande natura morta circolare con bottiglia e tre oggetti (Large Circular Still Life with Bottle and Three Objects, 1946).

Of all the examples on view at Pace, Grande natura morta scura (Large Dark Still Life, 1934) stands out for its atmospheric mood, a vision glimpsed in the spectral light of night. The darkness of this work is achieved through the compaction of thousands of etching lines. It is remarkable to consider the density of these lines and the master’s needle carving out each one. Mark for mark, you find more in a square inch of Morandi’s printmaking than in a foot of most modern multiples. You might say that Morandi is the high-thread-count etcher of modernism. The luxuriance of his work comes through in its feel rather than its mere appearance. Consider moreover that Morandi printed most of his etchings himself, sometimes in limited runs of only three or four, and you realize that each of these multiples is a rarified object in its own right, as intimate as any of his oils on canvas.

Intimacy is one aspect of Morandi’s art that poses a unique challenge to curators. Before there was “installation art,” there was simply art’s installation, an awareness of how stand-alone objects become informed by the space around them. I can think of few other examples of modern art that place such a high demand on their hanging as Morandi’s. Rather than reach out to us, Morandi’s paintings and etchings pull us in. It is true that Morandi’s work does not clash against itself—there are no bold colors, no conflicts of program—but his introverted works can tug at one another when arranged too close together. It is a common mistake to assume that Morandi’s intimacy demands proximity, when really his work benefits from open space.

The Metropolitan’s installation of its Morandi survey in the basement of the Lehman wing, a troublesome venue resembling an airport hotel conference center, could not be worse for appreciating Morandi’s particular touch. The Pace exhibition suffers in a similar way. Here the work is packed together in a small dark space, arranged chronologically, clockwise around the room, left to right. Such an exhibition sacrifices pleasure for didacticism.

In terms of presentation, by far the most successful Morandi exhibition this month is now taking place at Lucas Schoormans in Chelsea.[2] Gallery-goers may recall that in 2004 Schoormans mounted a small exhibition of Morandi oils that became the hit of the season. This month the gallery follows up with an equally impressive display. From the open, light-filled space to the sky- blue color of the walls, Schoormans has mounted his exhibition with an eye for intimate detail that complements Morandi’s own.

The gallery’s ground floor focuses on Morandi’s compact oil still lifes from the 1940s and 1950s. His Natura morta (Still Life), rendered in a buttery batter of paint, here from 1953, nears perfection. I also like how a moderately sized still life from 1948 gets to take up its own wall, affixed by two simple screws. The minimal presentation shows Morandi at his elegant best. He seems thoroughly contemporary, rather than dusty and reclusive.

Upstairs, Schoormans has assembled an exhibition of works in pencil and, in fact, several of the same etchings found at Pace. You might wonder if there is anything produced by Morandi not on public display this month in New York—not exactly a terrible situation to contemplate.

It is a delight to find these repetitions and see the same work in different surroundings: just as at Pace, we find Ponte sul Savena a Bologna, Natura morta con bottiglie e brocca, and Natura morta a grandi segni, among others, but here in more congenial surroundings. I like how this presentation does not set out to be all-inclusive. Instead it aims merely to please. I also enjoyed seeing Morandi’s etchings alongside a few of his wispy pencils and watercolors on paper.

I suppose there is something for each side of the brain in these two gallery shows—a printmaking class at Pace, and a sentimental education at Schoormans. They are both worth visiting, and each benefits from the other. Pace and Schoormans also vary as to which of their limited prints is listed for sale. It’s quite a month when we can find two gallery shows of Morandi multiples at once. For this, indirectly, we owe thanks to the singular vision of Philippe de Montebello, a museum director who dares to mount a major survey of this quiet modern master.

Notes

Go to the top of the document.

- “The Etchings of Giorgio Morandi” opened at Pace Master Prints, New York, on September 18 and remains on view through October 18, 2008. Go back to the text.