Gabrielle Evertz, Four Reds + blue green © Gabrielle Evertz

THE NEW CRITERION

June 2009

by James Panero

On Op Art, Gabriele Evertz at Metaphor Gallery, James Little at June Kelly Gallery & Nicolas Carone at Lohin Geduld Gallery.

The excellent optical painters working today are the survivors of a peculiar history. Back in the mid-1960s, the hard-edged abstraction that arrived under the banner of Op Art turned into a bad trip for high modernism. No other art movement blew up and burned out quite so spectacularly.

In 1965 William C. Seitz at the Museum of Modern Art organized a blockbuster exhibition of Op Art called “The Responsive Eye.” The artists in this show dispensed with the gestural brushstrokes of Abstract Expressionism. They largely did away with the naturalism of oil on canvas. Drawing on the intensity of new acrylic paints, they used contrasting lines and complementary colors to accentuate the biomechanics of perception. The results were immediate. Although grounded in over a century of study, the flickering, throbbing, pulsating works on view required little explanation. The show set attendance records. It was a sensation—and a problem. Up against 1960s popular culture, optical art came to be appreciated for its sociological relevance rather than its formal innovation. Its designs were exploited for commercial and cultural ends.

The optical artists in the MOMA show had deep roots in the history of modern art and science. This ancestry could be traced back to Goethe’s Theory of Colors of 1810. Here Goethe first took note of the chromatic dissidence of light-dark interaction—the colors that can be observed along the lines separating white and black. Goethe also investigated the volatility of complementary (opposite) colors as arranged on a color wheel—red against green, yellow against violet, and so forth. The Divisionism of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, based on the research of Michel Eugène Chevreul, further advanced perceptual theory. Twentieth-century Constructivism connected the visual absolutes of geometric abstraction with Socialist idealism, which went on to inform the aesthetics of the Bauhaus.

Among the artists in “The Responsive Eye” was Josef Albers, a Bauhaus colleague of Johannes Itten and a patriarch of color theory who influenced a generation of artists at Black Mountain College and Yale University. Victor Vasarely came through Alexander Bortnyik’s studio, the Budapest center for the Bauhaus. Julian Stanczak and Richard Anuszkiewicz, one-time roommates at Yale, were Albers’s former students and also included in the show.

Yet just as the optical art of Russian Constructivism was appropriated (and later discarded) by Socialism, Op Art suffered a similar fate in the hands of 1960s pop culture. Serious painting was degraded into a mere fashion phenomenon. Time magazine coined the term Op Art in 1964. The facile alignment of perceptual art and Pop Art, which had infiltrated public consciousness at the start of the decade, gave optical abstraction an undeserved superficial gloss.

Bridget Riley, perhaps the most recognizable artist in the 1965 exhibition for her swirling black-and-white compositions, first noticed something wrong on her taxi ride from the airport to the MOMA opening. There in the shop windows off Madison Avenue, printed on the clothing designs, were her paintings. How the images from a yet-to-open art exhibition ended up on the ready-to-wear lines of Seventh Avenue can be attributed to Larry Aldrich, an art collector and dress manufacturer. With the acquiescence of Seitz, Aldrich purchased Op works before the show and created fabric designs for his Young Elegante line of clothing. Through his distribution of these textile patterns, which also included works by Stanczak, Vasarely, and Anuszkiewicz, Op motifs ended up on everything from lamps and upholstery to maternity wear and girdles. There was even Op cosmetics. Sears carried Op wallpaper. Pfizer used Op imagery on the packaging of its antivertigo medication.

Riley eventually sued for copyright infringement. Yet nothing could stop the transformation of Op from serious art into faddish design. The opening party for “The Responsive Eye,” heavily photographed and filmed (the young Brian de Palma made a documentary of it), featured women with beehive haircuts and Op clothing head-to-toe. Life magazine published a fashion spread of Op apparel photographed in MOMA’s own galleries. Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Women’s Wear Daily also covered the fashion extensively. As Riley noted in 1965, “‘The Responsive Eye’ was a serious exhibition but its qualities were obscured by an explosion of commercialism, band-wagoning and hysterical sensationalism.”

Art critics generally dismissed optical art. Barbara Rose in Artforum called it “mindless.” Clement Greenberg labeled it “novelty art.” Reviewing the MOMA exhibition in The New York Times, however, John Canaday praised Op’s mass appeal: “This is a very satisfying thing for a public that has been puzzled and offended by a long series of modern isms. Optical art has a combination of virtues new to modern art: it fascinates, even if for different reasons, both the esthete and the layman.”

In the later 1960s, the popular appreciation of Op affected the art a second time, as mod fashion gave way to psychedelic drugs. Commercialism had already damaged Op by the time of the MOMA show. Now acid kitsch brought it to a new low. In a survey of Op Art at the Columbus Museum in Ohio in 2007, the libertarian art critic Dave Hickey took note of this secondary appropriation by linking the art movement to drug use and sexual liberation: “What the special effects of optical art do, specifically, is introduce us to that ‘stranger [to ourselves].’ … It replaces the elite, intellectual pleasure of ‘getting it’ with the egalitarian fun-house pleasure of disorientation, of trying to understand something that you cannot.”

From international socialism to slimming fashions to acid trips, the aggressive sensuality and easy reproducibility of perceptual art proved to be its undoing. By the end of the 1960s, Op Art seemed over. Minimal sculptors like Tony Smith adopted the hard edges of perceptual painting for machined materials. Process artists like Thornton Willis restored the Ab-Ex brushstroke to painting while still investigating the perceptual ambiguities of complementary colors.

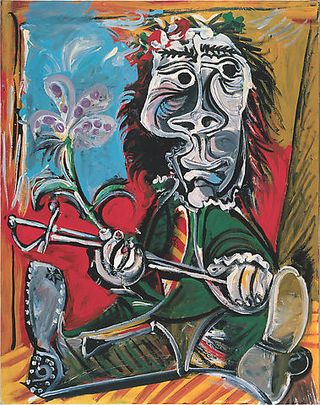

Yet Op Art never really went away as it was reabsorbed into general abstract practice. Generations of artists continued to investigate abstraction’s optical possibilities. Today the abstract painter Gabriele Evertz, who recently ended a group show at Metaphor Gallery in Brooklyn, draws a conscious connection with her Op Art forebears.[1] Evertz is an intense colorist who constructs her work out of precise vertical lines. A former student and now professor at Hunter College, Evertz is among the current generation of artists known as the Hunter Color School, initiated by E. C. Goossen in the 1960s.

Evertz tempers her optical effects with a more traditional interest in the overall mood of color. Reds, blues, and yellows alternately predominate on her canvases. Evertz also goes beyond the interference test-patterns of 1960s Op for more subtle modulations of tint, angle, and line. Colors leach and glow, but in beautiful rather than simply disorienting ways. Evertz gives perceptual art a new confidence in control and variation.

The abstract artist James Little is a painter for whom the term hard-edged is a gross injustice. His latest work is now on view at June Kelly Gallery.[2] While Little constructs his compositions in sharp angles and straight lines, his silk-like treatment of surface is uniquely his own. Little has developed his own encaustic medium, which he applies at high temperature in over twenty coats. With gestural brushwork, unlike his Op Art predecessors, Little is not easily duplicated.

For his earlier work, Little combed his shiny surfaces in rich layers of brushwork. At this latest show, he smooths out a more matte medium like the icing on a cake. The tone is softer than in previous iterations. Sharp punctuations have given way to a more even rhythm. Triangles have been compressed into more vertical arrangements. I miss some of the brushy surface, as well as the aggression of Little’s former primary palette. But the overall effect remains supremely assured. Work such as When Aaron Tied Ruth (2008) is particularly engaging and deeply enigmatic—a feeling you would never experience in work concerned with optics alone.

Today the power of paint, on full display in optical art, comes as a welcome tonic to a period in art dominated by Pop and Dada sculpture. Next up: Tim Bavington, a Hickey protegé born in 1966, whose chromatic work draws on Gene Davis. Bavington will be featured in his third solo exhibition at Chelsea’s Jack Shainman Gallery in September.

Finally, a note about time, and an artist who bends it. Born in Little Italy, New York, in 1917, Nicolas Carone is a second-generation Ab-Ex painter who studied with Hans Hofmann, knew Frank Sinatra, and introduced Cy Twombly, Joseph Cornell, and Robert Rauschenberg to the Stable Gallery, where he once worked. For twenty-five years, beginning in 1964, Carone taught at the New York Studio School. He later established his own painting school in Italy. Yet from 1962 to 1999, Carone largely kept his own developing art from public view. Now in his nineties, he is back with extraordinary fresh, youthful work. Mixed in with examples from the 1950s, Carone’s latest work is now on view at Lohin Geduld Gallery.[3]

A one-time representational painter, Carone is imbued with the history of classical art. In his sculpture, a few examples of which are on display in this show, he takes Italian stones and carves them into lost relics, bits of travertine figures rubbed and worn as though excavated from the bottom of the Tiber. The tactile crudity calls to mind the late sculptures of Elie Nadelman. Carone’s paintings similarly alternate between figural composition and abstract design, where the human form emerges and disappears from view. The best work here is almost entirely abstract. Carone’s line dips and curves without embellishment, carving out hints of the figure and moving with its own energy across the surface. Where Carone has rubbed out some areas of pigment, the line appears to dive beneath the picture plane. Ranging from classical painting to de Kooning, Carone’s diverse artistic influences emerge and disappear from view just like the figures in his compositions.

At Lohin Geduld there is the sense of encountering an emerging Abstract Expressionist artist for the first time. Like his lost Roman statues, his Old Master compositions, and his abstract designs, Carone is an anachronism and a thoroughly contemporary artist all over again.

Notes

Go to the top of the document.

- “Color Exchange: Berlin–New York” was on view at Metaphor Contemporary Art, Brooklyn, New York from March 27 through April 26, 2009. Go back to the text.

- “James Little: De-Classified” opened at June Kelly Gallery, New York, on May 7 and remains on view through June 9, 2009. Go back to the text.

- “Nicolas Carone: Abstraction/Figuration: Works on Paper” opened at Lohin Geduld Gallery, New York, on April 30 and remains on view through June 6, 2009. Go back to the text.