Patricia Watwood, Fate (2010), courtesy of the artist

THE NEW CRITERION

June 2010

Gallery Chronicle

by James Panero

On “Patricia Watwood: Portraits 2010” at Open Source, Brooklyn, “Michael Klein: Recent Paintings” at Arcadia Gallery & “Paul Resika: Recent Paintings” at Lori Bookstein Fine Art.

For years beaten down, another victim of the assault on representational art, traditional portraiture nevertheless endured. Although it had to cede its place in the limelight of high art, a premodernist style of portraiture survived the last century largely as a commercial form. Traditional portraiture filled the walls of libraries and law schools, government offices and private homes, but it remained largely absent from the nation’s art museums and the critical press. An argument could be made that, in the bargain, the last century’s portrait painters helped preserve the knowledge of the academic tradition. Untangle the genealogy of today’s realist revival—who taught whom in the movement sometimes referred to as “Classical Realism”—and the line often passes through a generation of portraitists living and working outside the mainstream.

A critical mass of younger painters in this art world in exile, the students of revivalists and illustrators, has emerged to challenge traditional portraiture’s second-class status and to reassert its place in the main currents of art. As these painters enter the full flowering of their talents, they are also discovering a culture that has grown more amenable to portraiture’s importance. We may be living, once again, in portrait-friendly times.

Recently I took part in the Portrait Society of America’s annual “art of the portrait” conference, this year in a suburb of Washington, D.C. Established in 1998, the PSOA began as an educational clearing house for the portrait trade. Its annual conference has become something more. Along with its displays of natural pigments and tutorials on such concerns as “Hands: What’s the Point?” and “Simplifying the Mystery of Flesh Tones,” the conference has become a watering hole for the country’s best young revivalist painters, who aim to take the art of the traditional portrait beyond the commercial commission.

My official role at this year’s conference was to appear in a panel discussion on “Realist Revolution and Critical Relevance: Is The Mainstream Media Missing an Important Cultural Trend?” My co-panelists were the painters Jacob Collins, the New York-based champion of the classical atelier, and Alexey Steele, an L.A.-based exile who made off with Soviet Russia’s entire reserve of charisma. Rounding out the panel was Vern Swanson, the director of the Springville Museum of Art in Utah, one of those few national institutions amenable to contemporary art painted in a traditional mode. The moderator was another young painter, Jeremy Lipking, also from Los Angeles.

The quick answer to the topic question was, yes, the mainstream media is missing out on realism’s revival, brought about by a renewed study in the classical painting techniques of the nineteenth-century academy. Why? Because of a political correctness that has associated representational art, at various times, with both Fascism and Communism —and because Pop and its market champions have elevated bad technique over good. For most critics the story of this revival remains tainted by politics, while the paintings’ craft remains outmoded.

But that’s all in hindsight. How about the future? At the time of the panel I had little to offer—just certainty that, were this particular “realist revolution” to come, the critical establishment would be the last to know. In the days and weeks after the conference, a more satisfying answer came into view: Today’s young realists, trained in the classical tradition, are a social group. I absorbed the full meaning of this note-to-self only after I returned home and checked in online. I discovered that these realists are connected. The fact that they do not appear to despise each other’s work, like so many other artists do, is itself revelatory. I doubt that any other artistic milieu, per capita, maintains a more active social network of Facebook, Twitter, and weblog accounts. These artists posted so much about the conference—videos, sketches, photographs, discussions, notes from the field—that they must have analyzed every moment of our time at the Hyatt Regency Reston.

Of course, much of their sociability has emerged out of necessity. Without the patronage of museums or traditional schools, realist painters have been forced to find ways to organize themselves outside of regular art-world channels. They have to be extroverted. But their networking also speaks to a renewed cultural interest in the connections of society, to which traditional portraiture can contribute. There is a reason an ever growing number of artists is lining up for portrait classes. Unlike the inward vision of modernism, in portraiture we find a social art for a social generation.

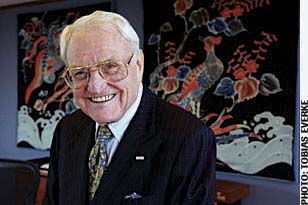

Like a form of social networking, portraiture is a display of connections—here between artist, subject, and viewer. In this understanding we may find a secret to the portrait artist’s success or failure—not necessarily in the quality of the paint handling, but in the vitality of the network. Portraiture has long been building connections to the real world in a network that only grows over time. Even back in the dark days, the traditional portrait painter’s standing could be based, in part, on the social ranking of the commissions: Presidential, royal, and ecclesiastical portraitists at top; the corporate, judicial, and celebrity painters in the middle; and finally the university-dean trade. Many of these painters have become the elders of the Portrait Society: Everett Raymond Kinstler, Daniel Greene, Burton Silverman, and William Draper, to name a few.

Today’s younger portraitists build their network on the creativity of their connections rather than on the heft of the commissions. Informed by Classical Realism, they often have a more fundamental approach to the canvas than do their predecessors trained in commercial illustration. By eschewing photographs and other modern conveniences, these younger artists often trade expediency and the gauzy conventions of commercial work for greater aesthetic vitality and a more fundamental connection among painter, subject, and viewer—connections that can be lost when a painter works from photographic studies.

The careful selection of subject has long been a secret of non-traditional portraiture’s success in the mainstream. Think of Chuck Close on the composer Philip Glass, or Lucian Freud on the performance artist Leigh Bowery. More recently, Kehinde Wiley has built a cottage industry out of painting hip-hop celebrities in the mode of Jacques-Louis David. Elizabeth Peyton has turned cocktail-napkin doodles of rock-star friends into prized creations. One might even consider Warhol and his Factory subjects as a sort of portrait circle. Now it falls to the classically trained portrait painters to extend their craft to a population that calls out for a more genuine connectivity free of celebrity culture.

One realist who has taken up this call is Patricia Watwood. Fresh from the conference, Watwood has mounted an exhibition of her portraits in a small gallery called Open Source in Gowanus, Brooklyn.[1] An artist who both works and lives in the area around the gallery, Watwood finds her subjects in her own neighborhood: a student, a filmmaker, two members of her local congregation. She writes in her artist’s statement: “The connection of the spirit between painter and subject, and between the subject and the viewer, shows the resonance of all human interaction.” Unlike many of her classically trained contemporaries, Watwood had developed an idiosyncratic palette that often casts her images in greens and blues rather than the “brown sauce” of traditional painting. The effect leaves her work with an alien glow, strange and other worldly. Her best portraits, like her figurative nudes, are those that capitalize on this strangeness. Dorothy (2010), the “church lady,” is a fine example: an unnaturally centered head-shot frames the subject in a totemic gaze. The longer portrait of Fate (2010), a “gospel and jazz singer,” has an equally compelling face, but I found the rendering of the shirt distracting. When set against Watwood’s particular affinity for physiognomy and skin, such materials lack urgency. A smaller self-portrait, Myself (2010), in which Watwood gazes out of the canvas with an inquisitive expression, is the show’s most compelling painting as the artist-subject brings the theme of the series full circle.

Another realist from the conference, Michael Klein, also has an exhibition of recent work on display. Like Watwood, Klein is a product of Jacob Collins’s ateliers, and his work hews closely to the Water Street style—so-called after the street address of Collins’s first school in Dumbo, Brooklyn. Klein has just returned from living with his wife in her native Argentina. His extensive selection of paintings at Arcadia Gallery in May placed her and her family in genre scenes of rural life.[2] The Wash Girl was last on display at the portrait society conference, where it was a finalist in a competition that also featured excellent work by Kate Sammons, Scott Burdick, as well as Lipking—an artist whose paintings go up at Arcadia in June. The curve of the wash girl’s pose, which finds her holding a pail by a stream, is nearly flawless. Her heavy eyes combine with a small half-smile that speaks of heavy labor and, perhaps, relief at our arrival. The background landscape, alas, is less convincing. The rendering of the water is clichéd. In the hanging at Arcadia, which put the painting in unfair light, the flesh tones lacked the suppleness of Collins’s work. Klein adopts Collins’s approach to paint handling, but here the technique has left too many regions of the large canvases incomplete. The open background of Late Night seemed unfinished. Where Klein excels is in his fine rendering of fabric and other objects. The galvanized metal of the wash girl’s bucket is exquisite, as is the satin sash and pillow of La Juventud and the black tulle of The Bride. Klein’s locates his connections in the exotica of a foreign world filtered through his contemporary family.

A final word about a must-see show. The painter Paul Resika has now found a home, after the collapse of Salander-O’Reilly Galleries, at the new Chelsea beachhead of Lori Bookstein Fine Art.[3] His first show at the gallery takes up the three bugaboos of modern subject matter—sunsets, sail boats, and lighthouses—and makes every brush stroke count. This latest work could be the basis of a tutorial on how to put paint on canvas. The geometry of the taut series marks out space in a constructivist shorthand of ships at sea. For such familiar subject matter, the work is a rare delight. Abstract and representational tension is at play while the color-rich brush work fills each shape with energy. Resika is a modern master delighting in his supreme command of color, line, and form—and it is a delight to behold.

Notes

Go to the top of the document.

- “Patricia Watwood: Portraits 2010” opened at Open Source, Brooklyn, on May 7 and remains on view through June 2, 2010. Go back to the text.

- “Michael Klein: Recent Paintings” was on view at Arcadia Gallery, New York, from May 13 through May 28, 2010. Go back to the text.

- “Paul Resika: Recent Paintings” opened at Lori Bookstein Fine Art, New York, on May 5 and remains on view through June 5, 2010. Go back to the text.