DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE

March/April 2012

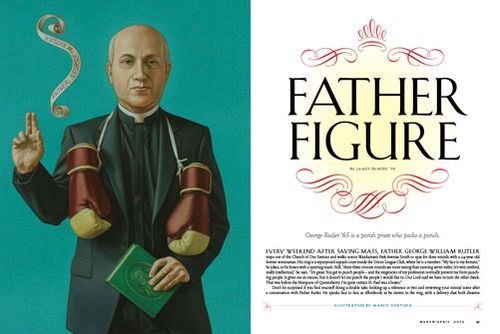

Father Figure

by James Panero

George Rutler ’65 is a parish priest who packs a punch.

Every weekend after saying Mass, Father George William Rutler steps out of the Church of Our Saviour and walks across Manhattan’s Park Avenue South to spar for three rounds with a 24-year-old former seminarian. His ring is a repurposed squash court inside the Union League Club, where he is a member. “My face is my fortune,” he jokes, so he boxes with a sparring mask. Still, “three three-minute rounds are more taxing than running seven miles. It’s very cerebral, really intellectual,” he says. “It’s great. You get to punch people—and the exigencies of my profession normally prevent me from punching people. It gives me an excuse, but it doesn’t let me punch the people I would like to. Our Lord said we have to turn the other cheek. That was before the Marquess of Queensberry. I’m quite certain St. Paul was a boxer.”

Don’t be surprised if you find yourself doing a double take, looking up a reference or two and reviewing your mental notes after a conversation with Father Rutler. He speaks face to face as effortlessly as he moves in the ring, with a delivery that both disarms and knocks you out. You might be looking up the footnote two comments back—John Douglas, the 9th Marquess of Queensberry, codified the rules of modern boxing—while Rutler has already moved on to his next combination.

Topics of discussion might include the depredations of International Style architecture, the teachings of the convert John Henry Newman or a recitation of “Men of Dartmouth” translated into Latin with full refrains. Dartmouth luminaries are never far from thought: the poets Richard Eberhart ’26 and Robert Frost, class of 1896; the Greek scholar Richmond Lattimore ’26; the appropriately named man of mystery James Risk ’37; the Catholic Dartmouth College chaplain “Father Bill” Nolan; and Bruce Nickerson ’64, a BMOC from Rutler’s undergraduate days killed in his prime, flying a combat mission over Vietnam. Each of these figures appears in Cloud of Witnesses, Rutler’s latest collection of essays with the simple subtitle, Dead People I Knew When They Were Alive. (It is his seventh book.)

“You get this constant awareness of history,” says Dartmouth trustee Peter Robinson ’79, who first met Rutler while working as a speechwriter in the Reagan administration. “I can recall being with him in a steam room in the Union League Club and within 30 seconds he was quoting Cato in Latin to the raised eyebrows of everyone else in the steam room. Cato is as completely alive to Father Rutler as Barack Obama—and certainly more respectable.” The same goes for Dartmouth, says Robinson. “To him Dartmouth doesn’t trail off into sepia tones. The whole history and life of the College, it’s all in vivid color.”

Our Saviour, Rutler’s parish of the past 10 years, is a Romanesque limestone pile that wouldn’t get a second glance on the banks of the River Rhone in medieval Avignon. Yet it was constructed at great expense less than 50 years ago, replacing an earlier plan for a glass-and-steel Bauhaus vitrine. The building’s provenance suits Rutler. This one-time Anglican son of Patterson, New Jersey, with an Oxbridge accent, the countenance of a 19thcentury theologian and the face of a Roman bust hasn’t become Dartmouth’s most famous Catholic in any straightforward way.

On the morning I meet with him in the rectory above Our Saviour, Rutler steps out of his kitchen in full clerical collar and cassock carrying two cups of coffee. One mug displays the slogan from the Polish solidarity movement, the other a line by Cardinal John Henry Newman, one of the more famous by the 19th-century reformer: “To be deep in history is to cease to be a Protestant.” Rutler jokes, “I like to serve my evangelical friends coffee in this.” The mugs seem to represent Rutler’s two sides, the sacred and the secular, each with a pointed world-view. After I suggest his coffee packs its own (bitter) punch, Rutler replies, “I’m sure those poor solidarity guys would be glad to have it.”

As the “baby of his class” who matriculated at 16, Rutler appears ageless and originless, even as he contemplates his own upcoming reunion in 2015. “When I was in college and people came to their 50th reunion [they] were on stretchers. Now I’m getting to the reading-glasses stage. It’s a male crisis thing. I think that’s why I’m doing the boxing.” He runs seven to 10 miles a day. He has defended Mother Teresa in a toe-to-toe encounter with Christopher Hitchens. He ministers tirelessly as the in-house chaplain to the American conservative movement. Still, when he claims, “I don’t like anything that causes perspiration,” take him at his word.

Rutler arrived at Dartmouth in the early 1960s “too stupid to realize how far away it was,” he says. “As a New Yorker, anything above 57th Street is Alaska.” Yet the school took him in, and he became the “kid brother” to many upperclassmen. Too young for team sports, he sang until “I was kicked out of the Glee Club when my voice changed,” he says. Rutler already had a sense of what he wanted do to in life. “I was Anglican,” he says. “I pretty much wanted to be a clergyman. I was set on that, I intuited that. I was very involved in the Episcopal student group.”

After graduation Rutler became the youngest rector in the country at age 26. He served as an Episcopal priest for nine years before converting to Catholicism. “I tell people it was because of the dental plan,” he jokes of his conversion and subsequent years in Rome during the papacy of John Paul II. His conversion came, in part, out of what he saw as political necessity. Always a conservative (a Young Republican in college, he campaigned for the moderate Nelson Rockefeller ’30 when he appeared on campus, support Rutler now regrets), he began to view the Episcopal Church as “Russia after the revolution. It was unrecognizable. The Catholic Church seemed to be stable against the political correctness of liberal Protestantism, which has now disintegrated totally. It was the best thing I ever did.”

Rutler’s ability to meld conservative instincts with Catholic doctrine and an erudite disposition brought him into the orbit of another expertly spoken conservative Catholic, William F. Buckley Jr., for whom Rutler delivered the homily during a requiem Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in 2008. The late National Review editor had maintained his offices a few blocks from Rutler’s former parish of St. Agnes, near Grand Central Station, and had connected Rutler with a younger generation of conservative Catholics, including those then emerging from The Dartmouth Review. It is no surprise that Rutler has officiated at every Review gala dinner in New York; hosted the Phrygians at Our Saviour when the Dartmouth senior society, formed around the petition trustee movement, came to town; and is a regular presence at conservative functions far and wide. For a decade he served as the national chaplain of Legatus, a powerful club of Catholic business leaders created by Domino’s Pizza founder Tom Monaghan. Then-governor George W. Bush even made Rutler an honorary Texan in 1996. “I have boots upstairs somewhere,” he says.

More than just clerical emcee, Rutler has shepherded a generation of Dartmouth graduates to Catholicism. Through Buckley he lined up a Catholic tutor for the young Peter Robinson as he worked toward his own conversion. “The day I was received formally in the church,” Robinson says, “George came down [to Washington, D.C.] from New York to receive me.” Recently Joe Malchow ’08, who founded dartblog.com as an undergraduate in 2004, became another Dartmouth son taken in by Rutler. “I was raised entirely a-religious, and as a young thinking man I was very excited about my atheism,” says Malchow, who became interested in the church after the terror attacks of September 11. In the summer of 2007, when Malchow was working as a summer fellow at The Wall Street Journal, “Peter Robinson told me, ‘You ought to meet this illustrious alumnus,' says Malchow. “It was the first Mass I ever sat through, and I sat all the way in the back.” Malchow has since undertaken Catholic instruction. “He is not an evangelist,” Malchow says of Rutler’s influence. “He knows what he knows and never once does he lean forward in an attempt at converting you.”

Within his own political circles Rutler can be equally influential. He has come to serve as the conscience of social conservatism and is a particularly harsh critic of the libertarian strain he sees influencing the conservative movement. Even regarding The Review, Rutler says, “They have to be very careful with what defines classical conservatism. The danger is to become postmodern libertarian rather than a real conservative. Where is the whole concept of natural law?” He is no fan of rock music: “People say I am a Cro-Magnon, but anyone who likes it has canceled himself out of the life of the mind.” He also bemoans the general dressing down of once-solemn ceremonies, including college graduation: “Tossing beach balls around is a subconscious realization that college education has become worthless.” Would it be shocking to know that Rutler did not care for the late-night host Conan O’Brien’s turn as graduation speaker this spring? “Mr. O’Brien said that vox clamantis in deserto was ‘the most pathetic school motto I have ever heard.’ Those pathetic words are the word of God,” Rutler says.

“He views Dartmouth College as holy ground,” says Robinson of the priest. “Why would anyone who graduated from Dartmouth in 1965 care two hoots about a commencement address in 2011 if he weren’t madly in love with the place? It’s like Robert Frost’s epitaph: ‘I had a lover’s quarrel with the world.’ ”

Perhaps Rutler’s most famous quarrel occurred in May 2007 at a conservative gala being held at the Union League Club. Following remarks by keynote speaker Christopher Hitchens, author of a diatribe against Mother Teresa called The Missionary Position, Rutler suggested to Hitchens that Mother Teresa was “in heaven that you don’t believe in, but she’s praying for you.” This sent Hitchens into the audience. Words were exchanged, and reportedly the two had to be separated. The two later made up, though Hitchens, who died of esophageal cancer in December, had written that “redemption and supernatural deliverance appears even more hollow and artificial to me than it did before.”

Death is a part of life for a parish priest. “I had six or seven friends die this summer. It was like a plague,” Rutler laments. Ten years ago, on September 11, Rutler saw more than his fair share of deaths. “I was at St. Agnes then,” he recounts. “I heard this plane and it sounded like it was right over [Grand Central] terminal. I thought, that’s a very big plane, why is it flying so low? And as I was thinking that I heard this distant thud. I immediately knew it hit something.”

Rutler ran three and half miles to the towers in lower Manhattan. “I was right there at the buildings. Everybody jumping. I remember the police going in and the firemen going in. Most of them were Catholic, so I was giving general absolution. Like on a battlefield, you can’t hear everybody’s confession.”

When Rutler went to the old St. Peter’s Church, a block from the World Trade Center, to retrieve holy oils, he saw the day’s first confirmed fatality. It was the body of fellow priest Mychal Judge, the fire department chaplain who became known as “Victim 0001” when he was killed by falling debris from the collapse of the south tower. “The interior of the church was all covered in dust,” says Rutler. “The priest’s body was brought into the church and the policemen were totally in shock. I remember one policeman crying on the steps. They didn’t know what to do, so they put the body in front of the altar. There was a painting of the Crucifixion, given by the King of Spain. It was a very graphic image. There’s the Crucifixion up there, the priest’s body there, and he was leaking blood down the altar steps. He was crushed.”

The memories of that day have kept Rutler away from Ground Zero since the attacks. When we meet, he is planning his homily for the 10th anniversary. Although the anniversary date fell on a Sunday, the church permitted its clergy to replace the standard liturgy with a special requiem Mass for the dead.

“We live as mourners,” Rutler told his parishioners, “never forgetting the wanton rampage of evil on that Tuesday whose late summer brilliance was so affronted by the moral darkness of those who blackened the bluest sky. These days pick up the pace from the pleasant torpor of summer, and on this particular day 10 years later, we also move on into a new decade to engage a cultural war against the moral offenses which have afflicted our time.”

In a world without sepia tones, the past is present and good and evil battle in vivid color. George Rutler sees himself as a cultural warrior in this battle, and he has never been more fighting fit.