THE NEW CRITERION

December 2012

The Armory Show at 100

by James Panero

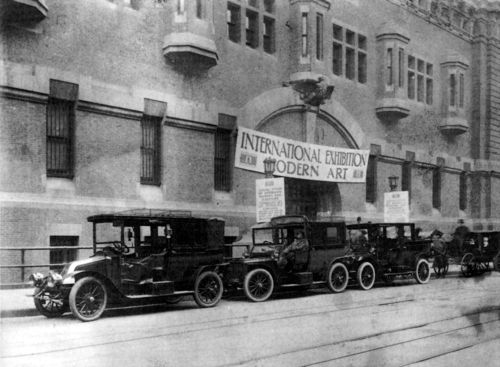

The lessons of the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art.

For a century, the 1913 “International Exhibition of Modern Art,” better known as the Armory Show, has served as a shorthand in the history of taste. Here is the exhibition that dazzled American provincialism with European sophistication. Here is the event that delivered American culture, kicking and screaming, to the world stage. Here is the moment that separates the reactionary past from the more enlightened present. We may remember little about the barnstorming tour that brought the latest paintings of Duchamp, Picasso, and Matisse—along with up to 1,200 other works—to New York, Chicago, and Boston, but we know enough not to make the same mistakes again. No longer will the avant-garde be dismissed, will progressive cultures be ridiculed, or will the masterpieces of contemporary art remain unrecognized. These have been the lessons of 1913. We are all Armorists now.

The centenary of the Armory Show should put these assumptions to the test. The year 1913 was more than the unofficial start of the twentieth century. It was a highpoint in both European and American cultural innovation. While the historic exhibition of the Armory Show contained some of the most advanced paintings and sculptures coming out of Paris, its most radical feature was the show itself, an American creation with an ambition, foresight, and appreciation of these developments that has yet to be duplicated. “No single event, before or since, has had such an influence on American art,” wrote the Whitney Museum director Lloyd Goodrich at the time of its fiftieth anniversary. Another fifty years on and this claim has only been confirmed.

The centenary will be a time to reflect not only on what we’ve learned over the past century but also on what we’ve forgotten, a reconsideration that is already underway. Starting December 6, WNYC radio will air a series of specials on the “culture shock” of 1913 featuring a broad survey of this annus mirabilis, from an 1963 interview with Milton W. Brown, who published his Story of the Armory Show around the fiftieth anniversary, to a consideration of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, to a colloquy on the zipper, invented in 1913 in Hoboken, New Jersey.

Just as the fiftieth anniversary of the Armory Show inspired impressive memorial exhibitions, at least two shows have been planned to coincide with the centenary. Opening on February 17, 2013—a hundred years to the day from the Armory’s inauguration—The Montclair Art Museum will launch “The New Spirit: American Art in the Armory Show, 1913,” an exhibition that will examine the Armory’s under-appreciated American art, which represented two-thirds of the original New York display. Then in October, The New-York Historical Society will mount a retrospective featuring over seventy-five works as well as materials about the history of the early Teens. The show will be paired with a catalogue promising thirty-one essays on the 1913 exhibition. While the Armory Show may now be only a vague historical event, by the end of 2013 we should all have given it a thorough reconsideration.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the cultural atmosphere of the United States, and of New York in particular, where the creative forces of the Armory Show took shape, shared more with the progressive developments of Europe than is often acknowledged. New, modern forms of art that broke with the salon styles of the academies developed in parallel on both sides of the Atlantic.

In 1908, a group of realist painters known as The Eight, all from Philadelphia, all ex-newspaper artists, exhibited together in a sensational show in New York that challenged the refinement of academic painting with a journalistic eye and “paint as real as mud.” Five of these artists—Robert Henri, George Luks, William Glackens, John Sloan, and Everett Shinn—became derisively known as The Ash Can School. A sixth member of The Eight, more of an idealist than a realist, was Arthur B. Davies, who went on to become the impresario of the Armory Show five years later.

At the same time, Alfred Stieglitz was showing both American and European modernist painting and sculpture at The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, at 291 Fifth Avenue, better known simply as “291.” In what Marsden Hartley called “probably the largest small room of its kind in the world,” Stieglitz mounted the first exhibitions in America of Henri Matisse, Henri Rousseau, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Francis Picabia, Constantin Brancusi, as well as African sculpture. He also gave the first one-man shows to the early generation of American modernists, including Alfred Maurer, John Marin, Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, Arthur B. Carles, Oscar Bluemner, Elie Nadelman, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Stanton Macdonald-Wright.

Although the realists and modernists were often at odds, the two American movements shared a dislike for the National Academy and New York’s circle of academicians, which controlled the city’s artistic establishment. With their record of off-the-grid exhibitions, the two camps developed a communal do-it-yourself spirit. In late 1911, several of these independent artists (including some academicians) came together to start an association that could serve as an alternative to the Academy and exhibit “the works of progressive and live painters, both American and foreign,” as this new “Association of American Painters and Sculptors” (AAPS) announced in its mission statement. “We do not believe that any artist has discovered or ever will discover the only way to create beauty.” Recognizing “the new spirit,” the association sought to “lead the public taste in art rather than to follow it.”

Arthur B. Davies, the association’s president, was a charismatic fundraiser and leader. Curiously, his charms also allowed him to carry on a bigamist relationship with two families that did not know about the other until his death in 1928. As the head of the AAPS, Davies became a “dictator, severe, arrogant, implacable,” the painter Guy Pène du Bois later remembered. He also drove the association’s remarkable accomplishments as both its heart and soul. For the inaugural (and only) exhibition of theAAPS, he thought big.

In 1912, Davies saw a catalogue for the Cologne Sonderbund Show, an historic survey of over six hundred modernist works, and decided he wanted a similar version for himself. Because of another commitment, he sent the association’s secretary, the painter Walt Kuhn, to Germany to investigate, advising him at the dock, “go ahead, you can do it.” Kuhn arrived in Cologne on September 30, the last day of the exhibition, and quickly took in this survey of Van Gogh, Cézanne, Gauguin, Signac, Picasso, and Munch. The swift assembly of the Armory Show had begun.

Later in November, Davies met up with Kuhn in Paris. Here, in a little over a week, the two engaged in a tour of the city’s most progressive cultural circles. After visiting the studio of the Duchamp brothers, Davies exclaimed, “That’s the strongest expression I’ve ever seen,” and promoted them extensively during the run of the show. They saw Odilon Redon in his studio, whose work would also be represented and appreciated. (“We are going to feature Redon big. BIG!” Kuhn exclaimed). When they visited Brancusi his studio, Davies said “That’s the kind of man I’m giving the show for” and bought a sculpture on the spot.

All of these introductions came by way of Walter Pach, an unofficial American member of the AAPS living in Paris. Through recent studies, in particular Walter Pach (1883–1958): The Armory Show and the Untold Story of Modern Art in America, by Laurette E. McCarthy, Pach’s full influence has only recently been acknowledged. Pach was the brains of the show. His eye and his connections secured the European components of the exhibition. He was also the key interpreter for the French avant-garde. He translated excerpts of Gauguin’s Noa Noa, the painter’s Tahitian journal, in one of the many widely distributed publications created for the show. His later translation of Eugène Delacroix’s Journal, published by Crown in 1948, is a modern classic.

Pach introduced Davies and Kuhn to the Stein family, those great American collectors of the avant-garde, who provided their own trans-Atlantic connections for the exhibition. They also demonstrated, like Pach, how modernism never developed in full isolation from the United States; even in Paris, it was as much international as it was French. Pach further persuaded Paris’s dealers to participate in the American exhibition. Ambroise Vollard, Durand-Ruel, Félix Fénéon of Bernheim-Jeune, Galerie Emile Druet, and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler lent much of the work to the show, which was supplemented by loans from American private collections and the artists themselves. The more historical paintings by the Impressionists, the post-Impressionists, and the Nabis—work that already enjoyed a robust European market—satisfied Davies’s desire to show the continuity of modern art, from Goya to the Cubists. For its creators, the Armory Show was about the evolution, rather than the revolution, of art.

All the while, Davies and Kuhn were arranging the logistics of the exhibition. For the New York show, Kuhn rented the recently constructed 69th Regiment Armory from the National Guard for $5,000, plus $500 for expenses. This building, which remains in service today on Lexington Avenue between 25th and 26th Streets, gave the Armory Show its unofficial name. At approximately 2200 percent inflation since 1913, that cost of the venue alone was over $128,000 in today’s dollars, a huge amount for a newly formed artist association. Davies found the money. In a matter of days, the AAPS divided the massive open space into twenty-eight octagonal cubicles and filled it with bunting and greenery that had been donated by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and her sister-in-law, Dorothy Straight. Kuhn, a master of publicity, built up the event even before the first patrons opened. Then, for less than a month, starting on February 17, 1913, the Armory Show became the school, the square, and the sensation of New York.

No admirer of modern art can help but dream of walking through those galleries. “Anyone with a drop of collector’s blood in his veins must develop a retrospective itch to have been there and had the same chance at prescience,” writes Milton Brown in his history. Consider the masterpieces that passed through those doors: View of the Domaine Saint-Joseph(1887), alternatively called Colline des pauvres or “The poorhouse on the hill,” by Cezanne, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Models (1888), by Seurat, now in the collection of The Barnes Foundation; Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra) (1907), by Matisse, now at the Baltimore Museum of Art; The Red Studio (1911), by Matisse, now in New York’s Museum of Modern Art; The Garden of Love (1912), by Kandinsky, now at the Metropolitan Museum; and, most famously, Nude Descending a Staircase(1912), by Marcel Duchamp, now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

What’s even more remarkable than the presence of these paintings—some of them barely dry—is the prescience of the visitors who saw them. We may not have a time machine to take us back to the Armory Show, but many of those who flocked to the exhibition found a machine that took them into the future. Mentored by Davies and Kuhn at the show, Lillie Bliss eventually assembled the twenty-six Cézannes that formed the nucleus ofMOMA. Alfred Stieglitz purchased five drawings by Alexander Archipenko, a drawing by Davies, a statuette by Manolo (one of several artists there who never became a household name), and the exhibition’s only Kandinsky, which he donated to the Metropolitan. The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, contains three of the Duchamps that were at the show, including Nude Descending a Staircase(originally purchased at the fair by the San Francisco–based lawyer Frederic C. Torrey). Katherine Dreier formed the Collection for the Société Anonyme, now at the Yale University Art Gallery, and Arthur Jerome Eddy formed his collection at the Chicago Art Institute.

While most of the work at the Armory would be considered a bargain by today’s standards, not everything was cheap. The Cézanne purchased by the Metropolitan was listed at $8,000 and sold for $6,700—or, adjusted for inflation, about $150,000 today. All told over its entire run, the Armory Show sold 35 American paintings and sculptures (for $11,625 total), 130 foreign works (for $12,886 total), and 205,000 tickets, leaving it with a slight profit at the end of its exhausting three-city run.

This is all not to suggest The Armory Show was universally embraced. While the New York press was generally favorable, often full of praise save for some cranky responses from the city’s establishment critics, the show’s reception at its next stop, The Art Institute of Chicago, was far less gleeful. The Institute’s academic student body staged public protests during the exhibition and even burned in effigy the figure of Walter Pach. Today this display sounds gruesome, but I suspect at the time it was meant to be somewhat jocular. Pach, after all, never went into hiding during his stay in the Land of Lincoln. In fact, this free publicity helped boost the Chicago run of the show, a smaller version of New York stripped of its American art component. At 100,000, Chicago had the highest attendance numbers of all three venues, compared to 87,000 in New York. At only 17,000, Boston proved to be a disappointing third stop in late April, one that says much about the “Brahmin mind,” writes Brown, and the city’s cultural passivity.

The Chicago press largely vilified the show, calling it “profane,” “blasphemous,” “obscene,” “vile,” “suggestive,” and a “desecration.” But Chicago also saw some of the Armory’s most eloquent defenders, in particular Harriet Monroe in the Sunday Tribune. “In a profound sense these radical artists are right,” she observed. “They represent a search for new beauty, impatience with formulae, a reaching out toward the inexpressible, a longing for new versions of truth observed.”

The excitement around the show, both in New York and Chicago, both positive and negative, speaks to the broad conversation the culture of art enjoyed in 1913. The heated response paralleled the modernist experience in Europe, where the 1913 Paris premiere of The Rite of Springdegenerated into a riot. “Of course controversies will arise,” predicted Davies, “just as they have arisen under similar circumstances in France, Italy, Germany, and England.” The responses were often colorful, for example the famous descriptions of Duchamp’s Nude as a “lot of disused golf clubs and bags,” an “orderly heap of broken violins,” “a staircase descending a nude,” and most famously “an explosion in a shingle factory.” Even former President Theodore Roosevelt took part. There is “no requirement that a man whose gift lay in new directions should measure up or down to stereotyped and fossilized standards,” he wrote in his own mixed review of the show, but the “lunatic fringe was fully in evidence.”

There is a reason that such an exhibition, with such energy, has never been repeated. We like to think we live in a post-Armory age, but we rather seem to be locked in a pre-Armory moment. Today our own cultural establishment announces its agenda with auction headlines. A professionalized museum class dictates the story of art to an increasingly passive public. A hundred years ago, the artists of the age said enough to their own academic culture. Without any government, academic, or institutional support, they found like-minded souls who helped nurture and propagate a renewed vision for culture. “Something is wrong with the world,” observed the banker James A. Stillman after seeing the Armory Show in New York. “These men know.” The Armory successfully cast aside “the dry bones of a dead art,” wrote Alfred Stieglitz. We should be so lucky if today’s academic thinkers similarly become the footnotes of history, and a resurgence in art once again captures the vital spirit of the times.