Loren Munk, Bushwick, 2013. Prints available through Supreme Digital.

THE NEW CRITERION

October 2013

by James Panero

On Art on the Block: Tracking the New York Art World from SoHo to the Bowery, Bushwick and Beyond by Ann Fensterstock; “Will There Be Any Stars in My Crown?” at Storefront Bushwick, Brooklyn; “Tom Evans: 1981” at Sideshow, Brooklyn; “Chuck Webster: Blessing” at Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York; and “Paul Resika: 1947–48” at Lori Bookstein Fine Art, New York.

Following the gallery trade is sometimes less about looking at art and more about studying the map. Galleries are the art world’s fluid dynamic. In the cities where they concentrate, they flow in unexpected ways, collecting and pooling in places you would never otherwise see or even imagine to exist. To be sure, these migrations are compelled by the need for space, the mandates of rent, and the effects that galleries have on the neighborhoods they occupy. A trickle of galleries is often followed by a deluge of gentrification that eventually washes out the artistic energy the galleries helped create. But economic imperatives explain only part of the cycle. Somewhere in the data points of a gallery’s who, what, where, when, and why, there is a story of the art itself and how it evolves within a mesh of creative networks connecting the landscape of a city.

For New York, this story is now told in a book called Art on the Block: Tracking the New York Art World from SoHo to the Bowery, Bushwick and Beyond.1 The author, Ann Fensterstock, has compiled a near-encyclopedic account of New York’s gallery movements over the past forty years. The narrative is dizzying and not altogether easy to follow, especially for anyone unfamiliar with its long stream of artists, galleries, and locations. Yet the book does a good job of identifying those early arrivals that shaped New York’s artistic neighborhoods, such as Artists Space in SoHo, Fun Gallery in the East Village, and Four Walls in Williamsburg.

In her introduction, Fensterstock rightly observes that galleries are driven by more than mere economics. Some of the galleries that owned their spaces in SoHo, for example, nevertheless decamped during the area’s mass exodus to Chelsea. What most determines the life and death of great artistic neighborhoods, she finds, is their concentration of artists, galleries, critics, and collectors—and the absence of everyone else. “One of the strongest factors that surfaced during my five years of researching this topic,” writes Fensterstock, “is the notion of arts professionals colonizing in like-minded communities.” Once a neighborhood becomes diluted by tourists, bargain hunters, and hangers-on, she adds, its creative essence moves off.

A hundred years ago, the modernists of Paris decamped from the overrun northern hills of Montmartre to the opposite southern pole of Montparnasse—a newer, less charming district, but one where they could more fully saturate the studios and cafes with their own artistic culture. The same thing happened in New York as galleries left SoHo in the 1990s, but here they split in two different directions. The more commercial gallery scene moved west, taking over the large garage spaces of far Chelsea by the Hudson River. The more experimental, alternative scene moved east, largely following the migration of artists in that direction. Each had a place, and the split hastened a dynamic that had already been set in motion in the early 1980s, when a flash of alternative galleries arose out of the punk chaos of the East Village. In the 1990s and early 2000s, their eastern momentum pushed galleries over the East River to Williamsburg, Brooklyn. In the last five to ten years, as the Williamsburg scene imploded through rapid gentrification hastened by an industrial rezoning, this eastern edge pushed further out to East Williamsburg, Bushwick, and Ridgewood. Meanwhile, a scene mixing aspects of both east and west, with more boutique commercial galleries, emerged on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

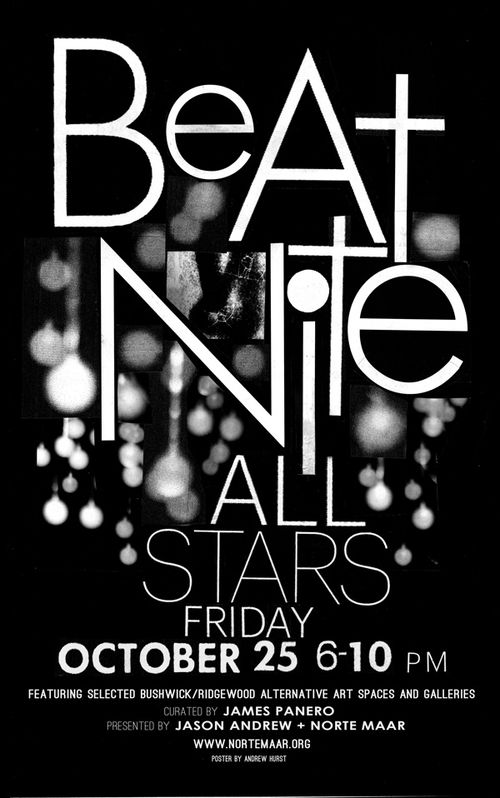

Art on the Block ends where Bushwick begins, but when the chapters about that neighborhood are written, the gallery known as Storefront will occupy an important part of it. At the time that Storefront opened on Wilson Avenue in January 2010, a dozen or so apartment galleries and alternative spaces were already spread across Bushwick (see “Gallery Chronicle,” February 2010). Many of these important early spaces were dedicated to showing the artists working in the area’s converted loft buildings, but they were also art projects in themselves, often hidden away, with little commercial intent. Founded by the curator Jason Andrew and the painter Deborah Brown, both Bushwick-based, Storefront aimed to be the neighborhood’s first truly professional outlet. Located in a tiny converted accountant’s office (the old signage remained for years), Storefront brought the Bushwick art scene out into the light of day with regular monthly exhibitions. It mixed in work by an older generation of artists (many of whom came of age in Williamsburg) and served as an access point for collectors entering the scene. This is not to suggest Storefront was a profitable enterprise. I would imagine that with art selling in the three-figure range, the economics were never there, even for a tiny Bushwick shop. Nevertheless, Storefront exposed Bushwick to a wider audience, collected many of its important early reviews and critical attention, and built a market for the art.

Now, not even four years after Storefront opened, Bushwick is a very different place. Upwards of fifty exhibition spaces are spread across the neighborhood. Galleries now concentrate in converted loft buildings such as 56 Bogart Street and 17–17 Troutman (just to indicate Bushwick’s fungible borders, the former is technically in East Williamsburg; the latter, in Ridgewood, Queens). The Chelsea gallery Luhring Augustine has opened a cavernous satellite space and storage facility in the neighborhood. One of the local restaurants serves a prix-fixe dinner for $195 per person.

Donald Roller Wilson, Beverly, 2005; oil on canvas, wood, frame with naturally shed deer antlers, 28" x 40"; collection of James E. Byrne and John C. Daniele, image courtesy of the artist

Now under the sole direction of Deborah Brown, who took the helm in 2012, Storefront Bushwick (as it is now known) has recognized these changes and is moving up. The current exhibition, “Will There Be Any Stars in My Crown?,” will be its last on Wilson Avenue before Brown relocates the gallery to a sweeping new venue on Ten Eyck Street in East Williamsburg.2

Curated by Todd Levin, Storefront’s most ambitious exhibition to date is also its most elegiac. With grayed out walls and a heavy curtain hanging over the shop window, the show feels like a melancholy send-off for a time that has already passed. The title of the exhibition comes from an 1897 hymn by Eliza E. Hewitt, which begins “I am thinking today of that beautiful land/ I shall reach when the sun goeth down;/ When through wonderful grace by my Savior I stand,/ Will there be any stars in my crown?” Different versions of this hymn play over a gallery boombox, with the work of three artists arranged on the walls like altarpieces.

Donald Roller Wilson paints meticulous portraits in a northern-renaissance style, with details down to the reflections in the drips of water. Yet his subjects are monkeys, not people, whom he depicts in elaborate frames (one is made up of naturally shed deer antlers), dressed up and smoking over-sized cigarettes. Jim Nutt, a Chicago artist who emerged in the 1960s with a group known as the “Hairy Who,” provides his own oddly precise black and white portrait drawings to the mix (here courtesy of Chelsea’s David Nolan Gallery). Jennifer Wynne Reeves rounds out the program with enigmatic abstract collages of spent pencils and daubs of acrylic paint. Taken together in this chapel-like space, the show falls somewhere between the sacred and the profane. The only certainty is the question mark of its title, with an answer that may only come in time.

Tom Evans, Feast, 1981; oil on canvas, 62" x 80"; image by James Panero

Richard Timperio’s Sideshow Gallery, a Williamsburg holdout, is dutifully dedicated to showing the work of artists who came out of the SoHo studio scene of the 1970s. Two years ago, Sideshow brought out the latest work of Tom Evans, a terrific abstractionist who had shown little in decades. Now Evans returns with a show of his work from 1981.3

Evans is a process painter. In his working loft in Tribeca, he has poured toxic metallic paint over canvases wrinkled on the floor, painted mind-numbing pointillist screens, and most recently swirled galaxies of color. For a brief moment in 1981, however, the fugitive images that are hidden in these abstractions came forward with monstrous intensity. Shapes and colors suddenly became grinning lips, crooked teeth, and bulging eyes. Some of this strange work was quickly snatched up and exhibited at The New Museum, but much of it has never left the studio until now. Truthfully, I doubt I would want one of these terrors above my sofa, but they are fascinating for what they reveal about the underlying forces of abstraction. Fortunately, we now have another chance to look at them, and for them to look at us.

Chuck Webster, Untitled, 2011-2012; oil and spray paint on panel, 48" x 48"; image courtesy Betty Cuningham Gallery

Betty Cuningham, a SoHo pioneer, today runs one of Chelsea’s best spaces for intelligent painting and sculpture, representing William Bailey, Philip Pearlstein, Rackstraw Downes, and the estate of Christopher Wilmarth. With “Chuck Webster: Blessing,” in cooperation with the gallery ZieherSmith, she incorporates a younger generation into the mix, and the addition is a worthy one.4

Chuck Webster, Sleeping Giants, 2013; oil and spray paint on panel, 84" x 120"; image Betty Cuningham Gallery

Webster is an expert paint handler who works his open, enigmatic abstractions down as much as he builds them up. He sands, cuts, and scrapes into his layers of gesso. Just when this manipulation might seem too mannered, he adds a few sprays of paint, like a bad touch-up job to a rusted-out car door. The effects give the paintings a rich patina. For “Blessings,” Webster draws from a visit to the Rothko chapel in Houston to paint glowing work that often references the space’s octagonal floor plan. Some of these paintings, such as Sleeping Giants (2013), rely too heavily on gothic effects. A smaller but more worked-over Untitled painting from 2011–2012, of a boxy red outline over a white ground with bits of blue popping through, is more enigmatic—less for what it depicts, and more for how it is depicted.

Paul Resika, Motor Shop, February 1948; Oil on canvas, 69 x 85 inches; Photo: Etienne Frossard, New York. Image courtesy of the artist and Lori Bookstein Fine Art, New York

The title of “Paul Resika: 1947–1948,” now on view at Lori Bookstein Fine Art, should alone provide a burst of excitement.5 Born in 1928, today Resika remains a consummate painter, with a masterful feel for oil on canvas. Since the 1950s, much of his work has come out of studying the Old Masters, but as a twenty-year-old prodigy in the late 1940s, he was painting in the thick of the New York School under the direction of Hans Hofmann, the influential teacher. The work from this period, now brought together at Bookstein, reveals an artist influenced by Matisse and Braque, but also one striking out on his own, with an edgier style ready to take on his American vision. Granted, some of these period works are more School of Paris studies than independent paintings—often admittedly so, as with the color-rich Dreaming (Matisse) (1947). Yet Motor Shop (1948) is definitely his own: a grisaille of roughed-out hooks and widgets, vice clamps and fan blades, and a raunchy pinup calendar. For an artist later known for his Italian influences, what surprises here is how rooted these paintings are in mid-century New York—with the Harlem River bridges, scenes of the Hudson, and the rattling doors of the subway. It wasn’t long after this moment that Resika realized there was an entire world beyond the city limits. Soon after these paintings were done, he went looking for it.

Paul Resika, Dreaming (Matisse), October 1947; Oil on canvas, 46 x 55 1/2; Photo: Etienne Frossard, New York. Image courtesy of the artist and Lori Bookstein Fine Art, New York

1Art on the Block: Tracking the New York Art World from SoHo to the Bowery, Bushwick and Beyond, by Ann Fensterstock; Palgrave Macmillan, 288 pages, $28.

2 “Will There Be Any Stars in My Crown?” opened at Storefront Bushwick, Brooklyn, on September 6 and remains on view through October 13, 2013.

3 “Tom Evans: 1981” opened at Sideshow, Brooklyn, on September 7 and remains on view through October 6, 2013.

4 “Chuck Webster: Blessing” opened at Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, on September 5 and remains on view through October 12, 2013.

5 “Paul Resika: 1947–48” opened at Lori Bookstein Fine Art, New York, on September 5 and remains on view through October 5, 2013.