New York’s Museum of Modern Art is one of those miracle products that turns out to have been a virulent carcinogen. How else to explain 53rd Street’s transformation from a vital home for living art into the malignancy it is today? Tumorous expansions have turned the block the pallor of sheetrock. Glass polyps sprout from every surface of Edward Durell Stone’s original building. At today’s MOMA, growth is not a sign of life but of continued decay; each development signals a more debilitating stage than the last.

This past month the downward spiral continued. MOMA announced its next expansion would doom the former home of the American Folk Art Museum, a building of recent vintage by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects. Folk Art had the misfortune of being built adjacent to the current Modern on land MOMA wanted for future development, in this case a tower designed by Jean Nouvel. (The proximity of the two institutions was no coincidence: Both museum properties were the products of Rockefeller philanthropy, reflecting the family’s shared interest in modernism and Americana. So much for donor intent.)

I’ve had mixed feelings about the Folk Art building, itself a symbol of the build-and-bust mentality that ends up ruining otherwise fine institutions. Construction of the Folk Art in 2001 broke the back of that museum, a problem that MOMA “fixed” by purchasing the property in 2011. Yet the townhouse-sized building, with its textured bronze facade, is also one of the more remarkable designs of the past several years. For a museum with a department dedicated to architecture, it stands to reason, one might think, that MOMA should first want to preserve the Folk Art by incorporating it into a larger structure—as the Metropolitan Museum has done with its many expansions throughout the years—before moving on to constructing the next glass shard.

MOMA’s demolition plans have drawn criticism from all sides, save for the schadenfreude of those who resent Williams and Tsien for their roles in relocating the Barnes to Philadelphia. That MOMA hired Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the celebrated architects behind the High Line, to deliver the coup de grâce did little to soften the blow. In the end it came down to real estate. Folk Art stands in the way of MOMA’s destiny to become a development complex that happens to have a Kunsthalle attached—a luxury apartment sprawl with restaurants, spa, and massage services offered by the Marina Abramovic Institute.

At the same time, and perhaps even more significant for today’s institutions, the MOMA build-out now proposed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro speaks to another alarming development: the mandate that large-scale work places on museums dedicated to contemporary art. In MOMA’s current plans, the Folk Art Museum, with its intimate interior spaces, must make way for a triple height “art bay” topped with a double height “gray box” space for exhibitions and performance.

What we see here is the endgame for large-scale work that began with Minimalism in the 1970s. Whether by accident or design, a movement that was supposed to liberate the avant-garde from the walls of the bourgeois salon has instead taken art away from the people and given it over to ever expanding institutions, which have become sick and bloated as they attempt to swallow all that mass and volume. (Just look to the current troubles at the Dia Art Foundation.)

Of course, truly revelatory work has never been size-specific. Alfred Stieglitz did not need a Tilted Arc. Gertrude Stein did not have a Rain Room. And rather than making work more radical, largeness now mainly makes art more institutional, since only multimillion-dollar museums with art bays and gray boxes are equipped to display, store, and commission it.

Installation view at Janet Kurnatowski

So it stands to reason that the real action these days is where the small stuff is: with smaller work that can be made more easily, collected, exhibited together, shared among artists, and transported for the cost of a subway swipe. The New Year welcomes two annual group shows to Brooklyn that present the smaller scale at its best, by bringing many of the talented artists in the New York studio scene together. With over 500 paintings and sculpture now at Sideshow Gallery in Williamsburg and over 100 works on paper at Janet Kurnatowski Gallery in Greenpoint, these exhibitions offer an unparalleled overview of a vital network of artists that largely gets overlooked by the museums and mainstream press.

Both exhibitions follow a similar program, with work arranged salon-style, and with an eye to the rhythm of the walls rather than the names on the labels. They also share many overlapping artists; both gallery owners, artists themselves, are exhibited in each other’s shows. The broad scope of each of the exhibitions means that they have evolved from a single vision into a crowdsourced installation, where artists invite other artists and the display takes on a life of its own. The result works out because each gallery started with a core group of impressive painters and sculptors—largely those who came of age in the Soho studio scene in the 1960s and 1970s, such as Thornton Willis, Peter Reginato, Joan Thorne, and Tom Evans. Here they connect to younger artists in the outer boroughs and across the country working through similar strategies. The worthy artists are too numerous to mention, but let me single out a few I spotted at both exhibitions: Loren Munk, Kim Uchiyama, Chris Martin, Dee Shapiro, Dana Gordon, Louisa Waber, Gary Petersen, Lauren Bakoian, Louise Sloane, Anne Russinof, Joanne Freedman, Elizabeth Riley, Kylie Heidenheimer, and Carol Salmanson.

Deborah Brown, Cloud , 2013; oil on panel; 11 x 17 inches

This past month saw two other group shows that sent me skyward. At Lesley Heller Workspace, the artist Adam Simon organized an exhibition called “Clouds” that pushed an old theme through endless new permutations, from paintings of cloud studies to sculptures of cloud bubbles. It helps that Simon, one of the founders of Four Walls, an influential alternative space that began in Hoboken in the 1980s and moved to Williamsburg in the 1990s, continues to be connected to many of the most interesting artists in New York. His group exhibition “Burying the Lede” at Momenta Art last fall turned the tables on the news cycle with artists ranging from Austin Thomas to William Powhida. With “Clouds,” he took many of the disparate artists of the Bushwick scene and uncovered their similarities, with work by Eric Heist, Deborah Brown, Brece Honeycutt, Sharon Butler, Paul D’Agostino, Kerry Law, Thomas Micchelli, Matthew Miller, Hermine Ford, Loren Munk, Edie Nadelhaft, Rico Gatson, Ben Godward, Larry Greenberg, Cathy Nan Quinlan, and Fred Valentine, among others.

Julie Torres at Kathryn Markel

At Kathryn Markel in Chelsea, the Bushwick painter Paul Behnke organized an exhibition of eight abstract painters who “hold the personal, the intuitive, the nuanced, and the hard-won in high regard,” as he writes in his catalogue essay. The selection pulled together artists from different scenes—Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Tennessee, and London—who would not regularly show together but clearly share a common sentiment for the power of paint “to best communicate the artist’s appetite and inventiveness.” With work by Karen Baumeister, Karl Bielik, James Erikson, Matthew Neil Gehring, Dale McNeil, Brooke Moyse, and Julie Torres, in addition to Behnke, the exhibition demonstrated abstraction’s ability to take in new energy and inventiveness, drawing on the artists of the past while mixing in the influences of the street and its rough, paint-soaked, paint-flecked, painted-over environment.

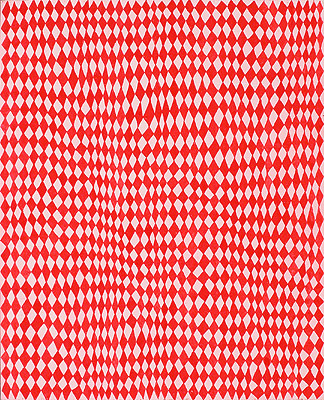

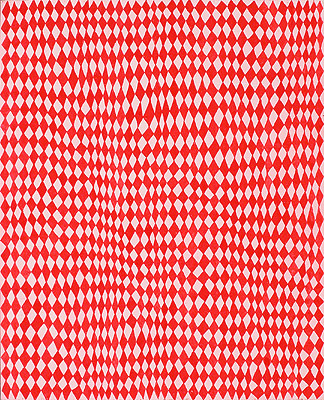

Lori Ellison, Untitled, 2013; Gouache on wood panel; 10 x 8 inches

At McKenzie Fine Art on the Lower East Side, Lori Ellison again demonstrates how small scale and simple materials can have the largest impact. With little more than ink on notebook paper and gouache on small board, Ellison shows how “compactness and concision can be a relief in this age of spectacle,” as she says in her artist statement (in addition to her paintings and drawings, Ellison is a pithy aphorist; her Facebook feed could fill a volume of Bartlett’s). This is Ellison’s second show at

McKenzie and her first in its new space, a change that, for me, brought out different qualities of her art. Ellison is able to work any doodle into an obsessive eye-catching skin, but this time I appreciated the simplest patterns most: the diamonds and hashtags that at first might appear dull compared to her more twisting, tentacle-like compositions but which captivated me the longer I looked. While their secrets remain a mystery, my guess is that the subtle variation in these drawings animates the repetition of shapes, leading to a surface that shimmers and images that come forward from beneath.

Angelina Gualdoni, Ballast, 2013; Oil and acrylic on canvas; 38" x 36"

At Asya Geisberg Gallery, Angelina Gualdoni, one of the founders of the influential Ridgewood gallery Regina Rex, reflects the polyglot practice we see in much painting today, moving from realism to abstraction and back again. A decade ago, Gualdoni was painting highly realistic scenes of decaying modernist architecture, inspired by Brasilia and elsewhere. Then the abstract components of these paintings overtook her compositions, which became all-over stains. Now, with her latest exhibition, she settles somewhere in the middle, which is a mélange of still-lifes and paint-pours. While I admire the uncertainty and adventurousness of these motions, what results in the latest work is a visual betwixt-and-betweenness, with aggressive compositions of color and light that nevertheless seem overwrought. Looking over the totality of her work, I get the sense Gualdoni is more at ease working in figurative space than on the picture plane, and she is certainly better at it. So when combined together in the same painting, the depth wins out, pulling us down into the work right past the pours. Her collages, which I’ve observed online, appear to balance better, with images floating more solidly on the surface.

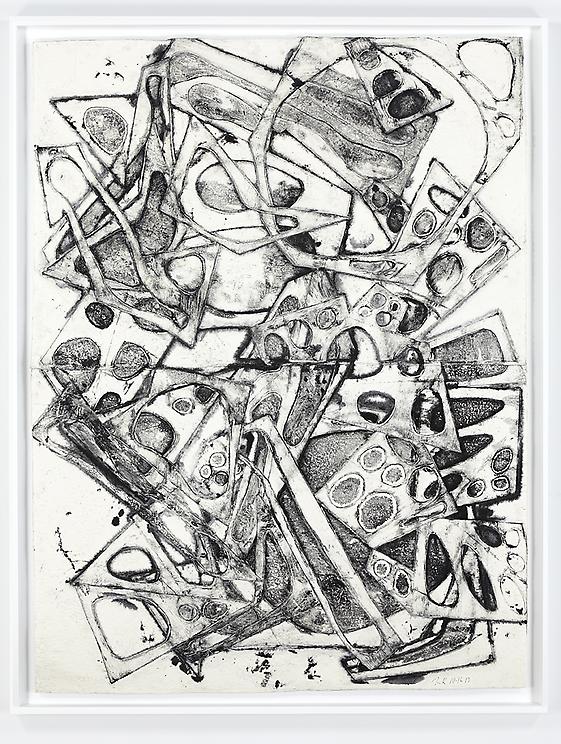

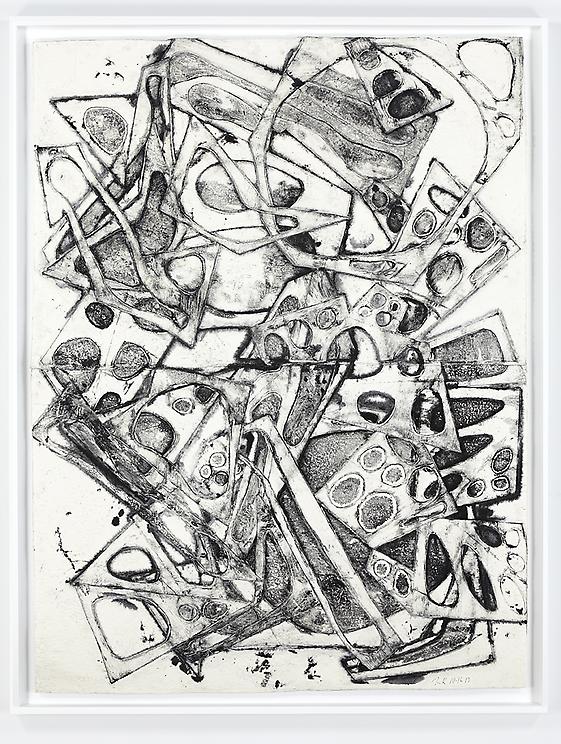

Mel Kendrick, Double Water Drawing, 2013; cast paper with carbon black pigment; 80 x 60 in, 203.2 x 152.4 cm

A final word about “Mel Kendrick: Water Drawings” now at David Nolan. I reported on these creations last month in my chronicle of the Miami fairs, where David Nolan first brought them to market at Art Basel. Like everything Kendrick touches, they are created through an intense internal logic that at first seems fully laid out but becomes more mysterious the more you observe. Like his sculptures made of positive and negative volumes, the “water drawings” are created through positive and negative molds, with shapes from a machine-age boneyard that Kendrick arranges flat before slopping on the paper pulp and squeezing out the water under pressure. The resulting “drawing” is itself a negative of the molds and exists in relief on the paper surface, which Kendrick also highlights with graphite. Now at Nolan, where several of these sheets are arrayed in the main gallery, we can see the evolution of the process. By increasing the complexity of the molds and lowering the contrast of the graphite, shapes not only sit on one another but thread together in a visual play, which was only enhanced as I walked around them and took in the surfaces undulating in relief. As with his sculptures, Kendrick knows he’s on to something. He may not know what just yet, but he knows it’s great.

“Sideshow Nation II: At the Alamo” opened at Sideshow Gallery, Brooklyn, on January 4 and remains on view through March 3, 2014; “Paperazzi III” opened at Janet Kurnatowski Gallery, Brooklyn, on January 17 and remains on view through February 15, 2014.

“Clouds, organized by Adam Simon” was on view at Lesley Heller Workspace, New York, from December 15, 2013 through January 26, 2014.

“Eight Painters” opened at Kathryn Markel Fine Arts, New York, on January 4 and remains on view through February 1, 2014.

“Lori Ellison” opened at McKenzie Fine Art, New York, on January 10 and remains on view through February 16, 2014.

“Angelina Gualdoni: Held in Place, Light in Hand” opened at Asya Geisberg Gallery, New York, on January 9 and remains on view through February 15, 2014.

“Mel Kendrick: Water Drawings” opened at David Nolan Gallery, New York, on January 16 and remains on view through March 1, 2014.