ART & ANTIQUES

April 2015

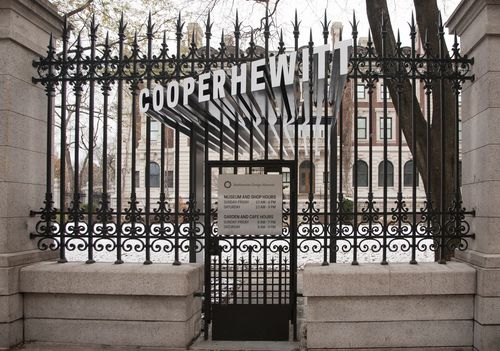

The Manor Reborn

by James Panero

The renovated Cooper Hewitt Museum harmonizes new, immersive exhibition spaces with the elegant, century-old infrastructure of New York's Carnegie Mansion

THE DECEMBER 12, 1902, inauguration of Andrew Carnegie’s New York mansion on Fifth Avenue, between 90th and 91st Streets, captivated the city and solidified Carnegie’s ambitions in brick, mortar, steel, wood, and stone. When the Carnegie family returned from their Scottish castle, Skibo, to see the home for the first time, a crowd gathered at the New York pier to greet the famous industrialist. “Why, I am fit as a brand new piston rod and solid as a rock!” he told waiting journalists. Across a city blanketed with snow, a team of horses carried the family through Central Park to what was then an underdeveloped neighborhood still far to the north of midtown high society. Arriving at the entrance, Carnegie turned to his five-year-old daughter Margaret, his only child, and gave her the key to their new home.

Since that first day, the keys of the Carnegie Mansion, on the heights of what came to be known as Carnegie Hill on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, have passed through several hands. In a ceremony following Louise’s death in 1946, Margaret handed over the same front-door key to the New York School of Social Work, part of Columbia University, which occupied the buildings for the next 20 years before moving onto the Columbia campus. Beginning in 1976, after losing the original support of the Cooper Union and being taken on by the Smithsonian, the Cooper Hewitt design museum has called the mansion home.

Following a three-year renovation—112 years to the day since the Carnegie family first set foot inside—the Cooper Hewitt has now handed over the keys for us to explore this museum in a mansion. In her diary entry for her first evening in residence, Louise Carnegie concluded she was “very pleased with the house.” With a revitalized museum, thoughtfully brought to life by 13 design teams working closely with museum staff through a $91 million capital campaign, we can all be very pleased.

Through the latest renovation, Carnegie’s original imprint has been brought back to the forefront of the mansion. At the same time, the Cooper Hewitt has been able to update its approach with the latest forward- thinking concepts in museum presentation, improved efficiencies, and a 60 percent increase in exhibition space (achieved largely by clearing out its underused third floor), all without enlarging the campus footprint.

The genius of the renovation has been not to fight old with new, but to find synergies between the two, tapping Carnegie’s own sense for design, education, and betterment through technology. For example, his was the first private residence in the United States to have a structural steel frame (supplied, of course, by his own state-of-the-art mills) and among the first to have an Otis passenger elevator along with central heating and air conditioning. Carnegie’s philanthropic vision, now manifested in the latest technologies of the revamped Cooper Hewitt, lives on through a principle he stenciled along the frieze of his library wall: “the highest form of worship is service to man.” Carnegie’s philanthropy was greatly inspired by Peter Cooper, the founder of the Coo- per Union, whose three Hewitt granddaughters created the initial design collection that formed the Cooper Hewitt. “I feel very proud,” Cara McCarty, the Cooper Hewitt’s curatorial director, explains. “We are repurposing a historic home, celebrating its design, not denying it or covering up the historic features. We’ve tried to work with it. And I think it makes our objects feel so much richer. Because it’s landmarked, there are a lot of limitations for what we can do with an intervention. We turned those limitations into an asset.”

By “knowing so well what we wanted to achieve,” McCarty says the museum avoided “the Bilbao syndrome” affecting many museums, in which spectacular expansions by celebrity architects take precedence over collections. The Cooper Hewitt’s sensitivity continues the approach of Lisa Taylor, its inaugural director, who maintained, “The use of an old building for a modern purpose is the essence of urban recycling, so...we have a museum that exemplifies in its facilities the very principles we are trying to communicate through our collections.” From its arrival in the Carnegie mansion, the Cooper Hewitt has respected the building’s original design, which helps explain why the museum now has so much to draw on for its latest revitalization.

The design of the mansion, by the architects Babb, Cook & Willard, reflected Carnegie’s desire to create a proper home for his family around art and nature that, given his extreme wealth, was still relatively modest in its exposed brick and Georgian style but full of personal details inside. The most sumptuous space, now newly restored, is the small second-floor family library, better known as the Teak Room, designed by the painter Lockwood de Forest. With intricately carved teak paneling from India decorating the ceiling frieze, corbels, door, and fireplace, the room is the most intact de Forest interior still in place. The room also shows the wide scope of Carnegie’s design interests, here drawing on the same Eastern influences that informed Olana, Frederic Church’s Persian-inspired country home in Hudson, N.Y.

“Tools: Extending Our Reach,” the inaugural exhibition in the new 6,000-square-foot third-floor Barbara and Morton Mandel Design Gallery, brings a cross-cultural 2001-like consideration to the instruments that make such design happen, with 175 objects ranging in date from a Paleolithic hand chopper to a live feed of the sun transmitted by an orbiting satellite. Especially impressive here is Controller of the Universe, a sculpture by Damián Ortega made of old hand tools suspended on string that appears to radiate from a central point that a viewer can walk through. There is also “Beautiful Users,” an exhibition on the ground floor that explores “user-centered design,” from thermostats to telephones to hand grips for kitchen implements to the latest in innovations for the handicapped to open-source 3D-printing “hacks” to connect Legos to Lincoln Logs. Next door, “Maira Kalman Selects” invites the beloved author, illustrator, and designer to “raid the icebox” of the permanent collection and tell a story with a selection mixed in with her own personal artifacts. Especially tempting here is a pair of trousers draped over a bench with a handwritten admonition: “Kindly refrain from touching the piano and Toscanini’s pants.” The “Process Lab,” in Carnegie’s sumptuous library, poses museumgoers with their own design challenges through hands-on interaction.

Among a host of new digital displays underwritten by Bloomberg Philanthropies, the “Immersion Room” stands out for using digital and projection technologies to help visualize wall- covering design in a new way. With access to hundreds of patterns digitized from the museum collection, and the ability to sketch their own designs on a digital table, museum goers can now see patterns projected full size and floor-to-ceiling on the room’s walls, rather than having to extrapolate from see- ing a single strip of paper.

Such interactive engagements elevate the making along with the made and use historical examples to challenge museum goers to think about contemporary design in a new way. The exercise is not all that different from the challenges faced by the Cooper Hewitt as the institution thought through its historic home.