"This Side of Paradise" at The Andrew Freedman Home, 1125 Grand Concourse, Bronx, New York (all photographs by James Panero)

James writes:

Has the periphery become the new center? It depends on where you look. In the art world, it was another month, another record price at auction, this time $120 million for a pastel version of The Scream by Edvard Munch. The news of such sales has become relentless. It’s the fine-art equivalent of the ticket-take for a summer-movie blockbuster, and it’s just as inconsequential. Despite the numbers, we all know the most interesting productions aren’t coming out of Hollywood. Same thing for art. The art scene flourishing on the margins of New York City now has a vitality you don’t see in Chelsea or the auction houses. The headlines might still focus on hammer price, but innovation, beauty, and significance are increasingly found elsewhere.

Not to suggest that great art has fled Manhattan. This month alone at the galleries, it is possible to see Frank Stella at L&M and FreedmanArt, a survey of Jean Hélion at Schroeder Romero & Shredder, Patricia Watwood at the Forbes Galleries, the drawings of Lucian Freud at Acquavella, Jan Müller at Lori Bookstein, and Giuseppe Penone at Marian Goodman.

It’s just that, now, the rippling-out of art from Manhattan to the outer boroughs has become a wave that rolls across Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. I doubt there has ever been a better time to see art in New York’s once marginal neighborhoods. The return of law and order has been matched by a cultural restoration energizing these forsaken places. At its best, art weaves itself into the local fabric by engaging the culture of the neighborhoods it touches.

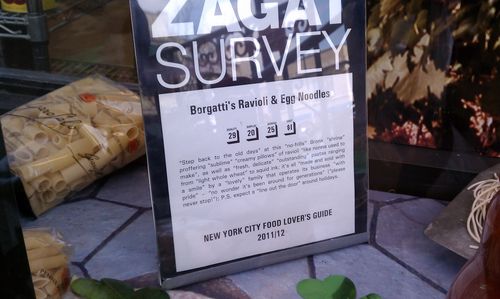

With a rich past darkened by decades of decline, the Bronx now seems especially bright. Frankly, I never would have guessed I’d find myself in this borough so often. But beyond the Bronx Zoo and the New York Botanical Garden, both treasures, and the unparalleled cuisine of Arthur Avenue, several recent art exhibitions have made the Bronx a must-see. It seems only fitting that the Bronx Museum of the Arts was recently chosen to represent the United States at the 2013 Venice Biennale; whatever its chosen artist, Sarah Sze, ends up creating at the Giardini, it will bring new recognition to this borough and will certainly be an improvement over what Allora and Calzadilla and the Indianapolis Museum of Art did there a year ago.

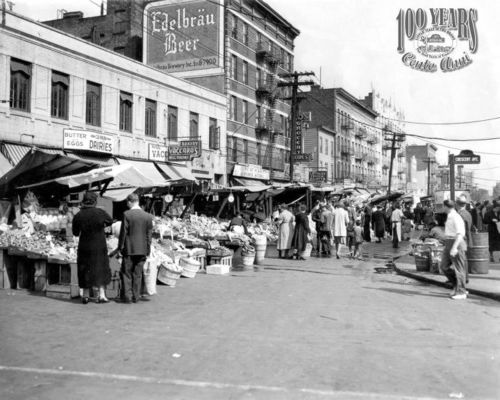

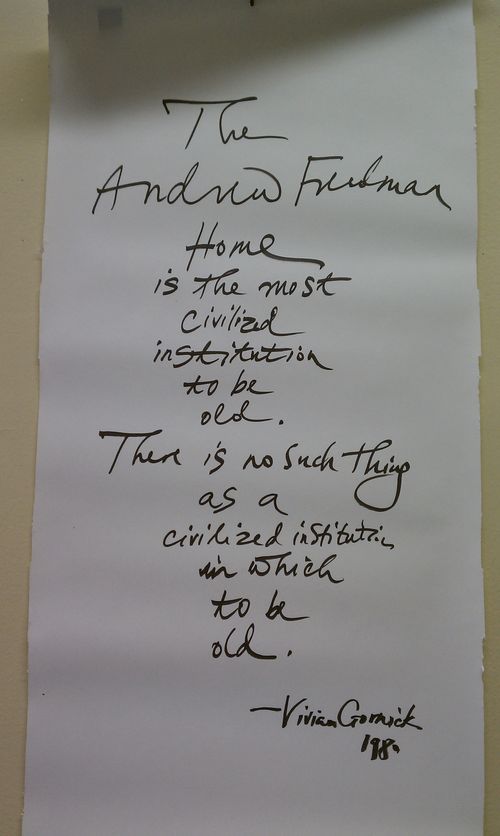

For the past two months, the highlight of art in the Bronx has been an exhibition called “This Side of Paradise.” The show was produced by an enterprising young non-profit called No Longer Empty, a cross between an arts organization and an urban policy project that creates site-specific art installations in unconventional urban spaces. “This Side of Paradise” is its most ambitious project to date and makes brilliant use of its unique venue, the Andrew Freedman Home. A four-story limestone estate, the facility was built in the 1920s along the Grand Concourse, the Champs-Élysées of the Bronx, to serve as a retirement home for people who had lost their fortunes. For decades it supported 130 or so elderly residents, but by the 1960s the home was running through its endowment just as the neighborhood was losing its middle-class population. Eventually its upper floors were abandoned. Even as it received landmark status, the building became a ruined reminder of the Bronx’s fading grandeur.

No Longer Empty cleaned up the first two floors of the Andrew Freedman Home, opened them up free to the public, and installed a thematic group show in the ballroom, library, kitchen, and resident rooms with art that aims to reflect the culture of the Bronx. The show has become something of a omnium-gatherum for the arts organizations of the borough, incorporating the Bronx Museum, the Bronx River Art Center, Casita Maria, the Bronx Documentary Center, the Bronx Children’s Museum, The Point, the Derfner Judaica Museum, and Wave Hill, among others, to guide and support various parts of this sprawling survey.

Even though the artistic quality varies, the overall effect is inspiring. Just as the Andrew Freedman Home once gave value to its residents, “This Side of Paradise” finds beauty in the home’s age and the building’s survival against the odds. The show brings together art that connects a lost culture, past and present, while for the most part avoiding didacticism and a fetish for decay.

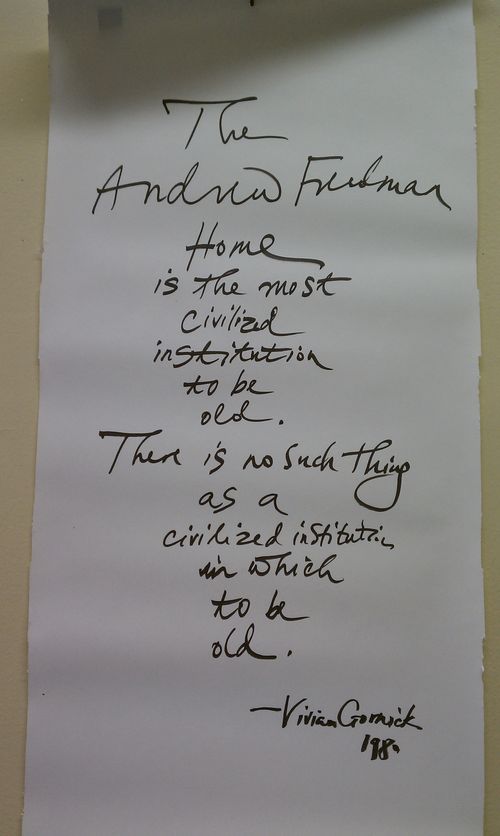

Of the many different styles and approaches on display, the most resonant is A Sitting Room: Remembering a Week in January (2012) by Sylvia Plachy. In 1980, Plachy came to photograph what would be some of the last residents of the Andrew Freedman Home while on assignment for The Village Voice. Her photos illustrated an article by Vivian Gornick. Now in Room 246, Plachy recreates the arrangement of objects she photographed, decorating the room with antique furniture, turning on an old phonograph, and printing a few spectral images of the former occupants on the walls and a billowing window curtain. Plachy says she was “drawn to the gentility of the residents” and wanted to pay “homage to those who once lived here.” It’s a sentiment that perfectly encapsulates the touching beauty of this exhibition.

Sylvia Plachy, A Sitting Room: Remembering a Week in January (2012)

The Princess Ballroom at "This Side of Paradise"

Federico Uribe, Portrait of Andrew Freedman (2012) and Persian Carpet (2012)

Justen Ladda, Three Eyed Red Mirror (22in x 34in, 2012), mixed media on red cedar wood, in the Princess Ballroom

Linda Cunningham, Paradise Lost/ Regained? Utopia to Survival (2012)

Nicky Enright, The Ravages (2012)

Sofia Maldonado, La Cocina (2012), site specific murals in the Kitchen.

Portrait of the Andrew Freedman Home

Key hooks discovered and rehung in The Andrew Freedman Home

Adam Parker Smith, I Lost All My Money in the Great Depression and all I Got Was This Room (2012, presented by Wave Hill)

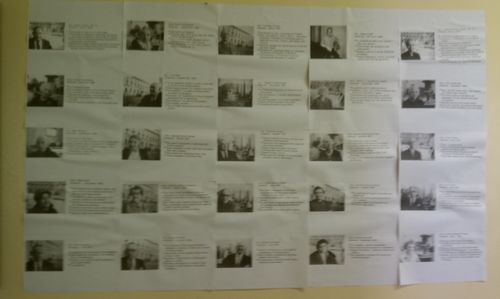

Images from the directory of former residents of The Andrew Freedman Home

HOW and NOSM, Recording Room (2012)

Cheryl Pope, Then and There (2012)

--adapted from "Gallery Chronicle," The New Criterion, June 2012.