THE WALL STREET JOURNAL, January 25, 2021

At the Clark Art Institute, six new outdoor works engage with the museum’s 140-acre campus. A review of “Ground/Work.”

As the pandemic compels us to take our culture al fresco, outdoor sculpture is having its day in the sun. The next day, however, might be partly cloudy. And the next might bring a frost with the chance of freezing rain. In other words the outdoors, unlike the white cube of a gallery, can challenge sculpture itself as much as the scenery compels us as viewers.

When the Clark Art Institute looked to bring art into the wilds of its own backyard in Williamstown, Mass., the muddy, icy, windswept challenges of a New England hillside called Stone Hill suggested an opportunity to do something different with sculpture than just display art plopped in a plaza, as we often encounter such outdoor work. An exhibition called “Ground/Work,” organized by guest curators Molly Epstein and Abigail Ross Goodman and on view through Oct. 17, now presents six commissioned pieces by six contemporary artists (all created last year) scattered around a 140-acre woodland pasture. This landscape with trails that rise several hundred feet and connect with a larger conservation area means visitors should be prepared for more than a walk in the sculpture park.

As an institution best known for its collection of 19th-century European and American art, the Clark is wise to use this outdoor space to bring contemporary voices and its natural assets into the mix. Through a language of reserved modernist form, each of these new works is designed to engage with the weather and the vistas, the birds and cows, all in “active dialogue,” according to exhibition literature, with this specific environment. It’s just too bad we need a field guide to some of the works in order to understand the overwrought concepts behind their creation.

You could easily miss the first work on view, which is embedded in the museum architecture itself. Jennie C. Jones has attached a 16-foot sculpture of powder-coated aluminum, wood and harp strings to the end of a free-standing wall. Called “These (Mournful) Shores,” the work is an Aeolian harp, meant to be strummed by the wind, that, according to the label, refers to the Middle Passage. It’s an elegiac idea but with layers of conceptual meaning that muddy the effect. Its dark gray palette, meant to recall that of two seascapes by Winslow Homer in the Clark collection, further mutes what should be a more resonant work.

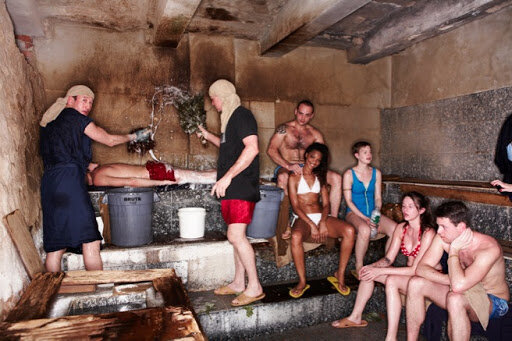

Head up Stone Hill for a three-part work by Haegue Yang. “Migratory DMZ Birds on Asymmetric Lens” focuses on three species found in the borderlands between North and South Korea. A lentil-shaped base of soapstone supports life-size clear resin models of these birds horizontally split in two. The bottom half of each model is an inverted form meant to serve as a birdbath for local species. If you missed all that, you are not alone. When it comes to innovative manufacturing, Ms. Yang cuts no corners. The Fresnel-lens-like striations of her soapstone are enigmatic and tactile. But derived as they are from specimen scans taken around the DMZ, her resin models are too clever by half and never take flight.

In a far corner of the grounds, Kelly Akashi’s “A Device to See the World Twice” trains an acrylic lens, over 6 feet tall, on an old ash tree that happens to have fallen after the sculpture was designed. Here an attempt at a rusticated frame holding up the lens detracts from the invitation to meditate on the natural ruin of the tree seen through it. For Eva LeWitt—daughter of Conceptualist Sol LeWitt—three thin “Resin Towers” of layered colored discs seem to bubble up like thermometers in red, orange and blue. On the day I saw it, the diaphanous forms got lost in the late fall light. But since “Ground/Work” will be on view through all four seasons, there will be ample opportunities for them to come alive again.

“Knee and Elbow” by Nairy Baghramian is the exhibition standout. This work of Carrara marble and polished stainless steel dances up the hillside in expressive skeletal form. Arching shapes mime the mountains beyond while two-toned stone refers to the white and pink facades of the buildings below. The bounding sculpture speaks for itself, no notes required. Now, if only it were bigger. This impressive work, just five feet tall, calls out for greater scale.

Returning to the Clark campus, we see a final sculpture. Analia Saban’s “Teaching a Cow How to Draw” is supposed to remind us of the cows’ presence on this active pasture by refashioning a working cattle fence into a visual tutorial for several theories of composition. It’s a conceptual joke, with forms built into the fence meant to represent the rule of thirds, the golden ratio, and two-point perspective. Having grazed on this last mealy offering of Stone Hill, I felt all-the-more ready to feast on the collection inside the museum.

SEE THE WALL STREET JOURNAL OF JANUARY 25, 2021 FOR THE FULL REVIEW

Haegue Yang’s ‘Migratory DMZ Birds on Asymmetric Lens Duiitt Vessel (Gray-Backed Thrush)’ PHOTO:HAEGUE YANG/KURIMANZUTTO, MEXICO CITY/NEW YORK/THOMAS CLARK