THE NEW CRITERION, January 2026

On “Renoir Drawings,” at the Morgan Library & Museum.

You never get a second chance to make a first impression, so the adman sayeth. Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) would beg to differ. The Impressionists were not the spontaneous image-makers they were made out to be. Sold to the public on the immediacy of painting directly from nature, these actualistes still held on to their studies and models to arrive at their finished work. Renoir was arguably the least impressionistic among them. A trained draftsman, he returned to drawing later in life to flesh out his most synthetic compositions. His efforts on paper reveal much of this artistic process. As he created increasingly layered iterations, these drawings came to serve as captivating works in their own right.

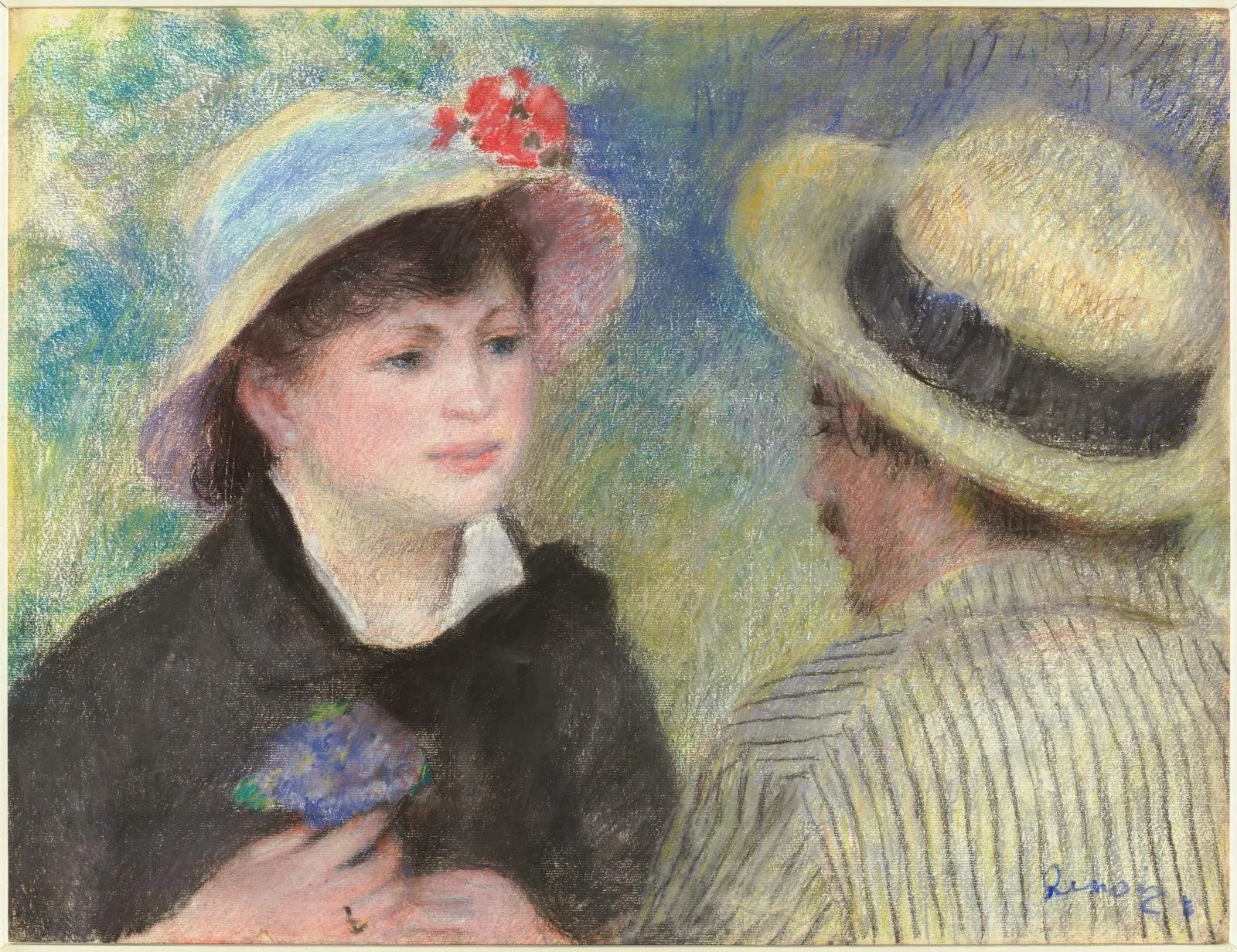

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Boating Couple, 1880–81, Pastel on paper, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. On view in “Renoir Drawings,” at the Morgan Library & Museum.

“Renoir Drawings,” now on view at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, is therefore something of an anti-blockbuster blockbuster.1 Even with its marquee name, the exhibition mostly avoids top-line works and Renoir’s core Impressionist years of the 1870s. Instead, the show digs down, at times way down, into Renoir’s paper record to draw up a newly intimate portrait of the artist across a fifty-year span. With detailed drawings packed into two galleries, the exhibition requires close attention, as displays on paper generally do. Works are small, behind glass, and in lower light (at times, also obstructed by glare). But the rewards of this significant show can leave us with a fresh impression of the Impressionist we thought we knew so well.

To get a sense of the importance that the Morgan, with its dual focus on literature and art on paper, has placed on this exhibition, look no further than its curator, Colin B. Bailey. Working with his research associate Sarah Lees, Bailey has done double duty here as the organizer of the exhibition while serving as the institution’s Katharine J. Rayner Director—the first time, in his decade-long tenure, that he has overseen his own show. “As a director of a museum,” he explained at the preview, “it is unusual, and perhaps not always very wise, to embark on a large exhibition, and we have spent seven years working on it.” In other words, as the first comprehensive exhibition devoted to Renoir’s works on paper in more than a century, this is an ambitious and expensive undertaking.

We are its beneficiaries, as its results combine significant loans with a thoroughly mined archive of works on paper. The exhibition presents one hundred drawings, pastels, watercolors, prints, and paintings from sixty-two lenders, with a plurality of loans from Paris’s Musée d’Orsay, where a version of the exhibition will be on view this spring.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of a Girl (Elisabeth Maître), 1879, Pastel on Ingres paper, The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna. On view in “Renoir Drawings,” at the Morgan Library & Museum.

Beyond his sketchbooks, Renoir composed some eight hundred independent works on paper. While other artists may settle on preferred subjects and formulas, Renoir employed his drawing widely, composing portraiture, mythological imagery, landscapes, still lifes, and scenes of modern life. Along the way, he worked through an adventurous range of graphic media: pencil, black chalk, red chalk (also called sanguine), white chalk, Conté crayon, charcoal, pen and ink, watercolor, gouache, and pastels, as well as printmaking with etching and lithography. All of the resulting works are fugitive and fragile, susceptible to light and movement. This makes their public exhibition here all the more rare.

A word should also be said for the accompanying exhibition catalogue, which features essays by Bailey, Lees, Flavie Durand-Ruel Mouraux and Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel (scholar-descendants of the Impressionist dealer Paul Durand-Ruel), and Anne Distel and Paul Perrin of the Musée d’Orsay. Published by DelMonico Books and printed in Trento, Italy, on uncoated Munken paper stock, each page feels like its own work on paper, with astonishing image fidelity. Those many other museums now outsourcing their catalogues to China, please take note.

While this exhibition has been seven years in the making, its initial inspiration took shape some two decades ago. That was when Bailey saw Study for The Great Bathers (ca. 1886–87 and 1908), a large work in red and white chalk on wove paper lined to canvas, while paying a visit to the home of Drue Heinz. A specialist in eighteenth-century French art and an authority on Renoir, Bailey saw Heinz’s drawing for what it was: a preparatory work related to Renoir’s masterpiece in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but one he had never encountered before.

The surprise reveal suggested how much of Renoir’s art beyond his famous paintings (he made some four thousand canvases) was still out there to be discovered. “Renoir’s works on paper form a considerable part of his oeuvre,” Bailey writes in the lead essay of the exhibition catalogue, but

as a corpus they remain somewhat uncharted, and occasionally treacherous, territory. Accuracy in dating and the correct identification of media are often lacking; a comprehensive and well-documented review of his development as a draftsman over six decades has yet to be written.

In life, Drue Heinz was not only a significant collector but also an important patron of the arts. Among her many philanthropies, she was the founding supporter of the New Criterion Poetry Prize. After her death in 2018, her estate offered the Morgan a work from her collection. Bailey requested her Bathers and set about creating this exhibition around the acquisition in her honor. While not a comprehensive catalogue raisonné, the result does much to advance Bailey’s own call for a “well-documented review of [Renoir’s] development as a draftsman.”

Renoir showed graphic talent from an early age. He drew until the end of his life. According to his son Jean, he “never let a day go by without sketching something.” Following his eldest brother, Pierre-Henri, who was an engraver of medals and gems, Renoir found early work in Paris as a designer, decorator, and draftsman for blinds, emblems, and commercial decor. He also apprenticed to be a painter on porcelain for Sèvres. As he moved on to training at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he pursued the traditional course of drafting and figuration and received a copyist permit for the Louvre.

The earliest works in “Renoir Drawings” are those from the early 1860s, with rather arid chalk-and-graphite studies on paper of paintings and sculptures. As he turned to Impressionism in the 1870s, his portrait pastels become a highlight. Here his tender 1879 Portrait of a Young Girl (Elisabeth Maître), on loan from the Albertina Museum, Vienna, is a standout. So too Boating Couple (1880–81), on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and The Milliner (ca. 1879), from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The exhibition becomes most illuminating as it gathers studies and versions of the same compositions together. Renoir’s Dance in the Country (1883), one of the significant oil-on-canvas loans from the Musée d’Orsay, is accompanied by a suite of paper studies and related prints on loan from other venues. The same for Motherhood (1885), another oil on loan from the Musée d’Orsay.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Great Bathers, 1886–87, Oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art. On view in “Renoir Drawings,” at the Morgan Library & Museum.

A turning point for the artist, and this exhibition, is The Great Bathers (ca. 1886–87). A suite of seven studies, including the Heinz bequest, is centered around the oil on canvas from the Philadelphia Museum of Art (which is only able to travel due to a change in its loan agreement in 2020). Here his drawings are canvas sized, as though he designed to transfer them as one-to-one components, like Renaissance cartoons, to his finished work. The final composition conveys this sense of multipart assembly, with its nude female figures seemingly detached from one another and unreal. Such unreality was no doubt purposeful, as Renoir moved away from the contemporary in favor of an idealized, friezelike antique.

“Around 1883,” the artist recounted to the painter Ambroise Vollard, “I had come to the end of Impressionism, and realized that I knew neither how to paint nor to draw.” Instead he traveled to Italy and took to Raphael. In what is called his rappel à l’ordre, he abandoned being a painter of modern life to focus on the classical nude. The subject matter brought him back to his student days of the 1860s, but now informed by a new Impressionist sensibility for luminosity and color. As he explained to his dealer Durand-Ruel in the fall of 1888, “I have returned . . . to the old style of painting, soft and light. Like Fragonard, but less good.”

Renoir pursued the classical nude into the early decades of the twentieth century. One of the final works here is his Study for “The Judgment of Paris” (ca. 1908) from the Phillips Collection. The related oil, in the Hiroshima Museum of Art, did not travel, but a patinated plaster relief of the composition that Renoir composed with the sculptor Richard Guino is here from the Musée d’Orsay. These final works represent how Renoir carried on even after he became too infirm from arthritis to hold soft media such as pastel and charcoal. (An early film in the museum’s introductory hall shows him at work in old age.)

Throughout his life, friends and critics alike remarked on Renoir’s drafting skills. An early critic for La Liberté called his drawing “neither frigid nor fixed; it is alive, animated, and intelligent. It has infinite delicacy and subtlety.” The decadent novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans compared Renoir to Chardin and said his portraits were even more “captivating, individual, and incisive.” In her journal, the close friend and fellow artist Berthe Morisot called Renoir a “draftsman of the first order” on a studio visit in January 1886, after seeing a suite of drawings in red and white chalk around his Motherhood composition:

He showed me a whole series done from the same model with about the same movement. . . . it would be interesting to show all these preparatory studies for a painting, to the public, which generally imagines that the Impressionists work in a very casual way.

Across Renoir’s span of four thousand paintings, did he make a bad one? He certainly did. Some of his late-career nudes, such as the bumper crop now in Philadelphia’s Barnes Collection, have long been criticized as overdetermined and fleshy. Judging from the selection now at the Morgan, however, the same does not hold true for his drawings. Provisional drafting may have taken Renoir’s paintings away from the precepts of Impressionism. Ranging across multiple styles and media, his drawings meanwhile remained open, experimental—even, we might say, impressionistic.

“Renoir Drawings” opened at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, on October 17, 2025, and remains on view through February 8, 2026. A version of the exhibition will also be seen at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris (March 17–July 5, 2026). ↩