You don’t have to be an art critic to see something tasteless going on at Pratt Institute. Since 1887, this venerable New York institution has been dedicated to educating “artists and creative professionals to be responsible contributors to society.” Yet teachers and administrators at Pratt have been nothing but irresponsible in their recent dealings with a fifth-year drawing student named Steve DeQuattro.

Mr. DeQuattro is a political artist. He uses his background in graphic design to illustrate the dominant political culture of his world. At Pratt, this means creating work that addresses, as he wrote to me, the “growing bureaucracy, higher tuition, new buildings for administration, new offices, and departments, and left-wing bias, all at the expense of the students.”

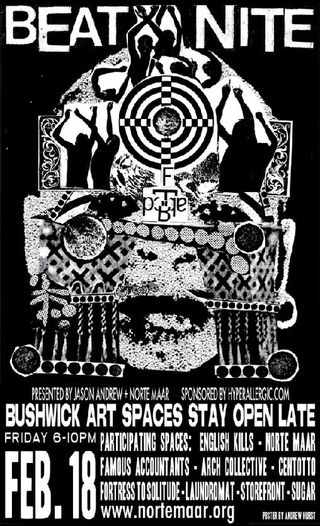

As part of his recent work, Mr. DeQuattro has designed a cereal-box-like sculpture that he calls, ironically, “Sustainable Liberalism in a Box” (the graphics are pictured above). He has developed a piece that takes the ubiquitous Apple iPod ad campaign to address abortion. He has designed a sobering five-foot-wide mural that tracks the Democratic Party’s record on race, from Jefferson’s slave-holding days up through the racially charged speeches of Senator Robert Byrd and Vice President Joe Biden.

As a senior in the school, Mr. DeQuattro has been working on this art in preparation for a group show for Pratt’s graduating students, which is scheduled to open on April 23. While his faculty advisor has been supporting him, his peers have not. Mr. DeQuattro says they recently wrote a letter to his professors, calling his work “offensive” and complaining about exhibiting alongside him. Last week, the chair of the fine arts department stepped in to prevent Mr. DeQuattro’s participation alongside the other students in the group show--an unprecedented move in the history of the department, says Mr. DeQuattro, despite the fact that none of his work is pornographic, libelous, or in violation of the laws of free speech. Mr. DeQuattro's advisor did not return a request for comment.

For the administrators and students at Pratt, the problem isn’t political art itself, says Mr. DeQuattro, but the nature of his politics, which are conservative. He says his school takes a liberal position on politicized discourse, just as long as that discourse does not deviate from a left-wing position. Pratt’s opposition to Mr. DeQuattro’s art only underscores the importance of his work. Mr. DeQuattro is asking for outside help in convincing the institution to support his exhibition.

Mr. DeQuattro's case illustrates the art world's double standard towards political art. From Jean-Louis David’s Death of Marat to the works of George Grosz to Picasso’s Guernica, political commentary has had a place in the history of art. Artistic expression can help us understand politics in ways that other forms of commentary cannot.

Yet the relationship of artist to audience often tells us much about the validity of political work. Art that preaches to a wholly agreeing public is little more than propaganda. Most self-described political art today falls short in this regard and is of limited value outside of its political utility, because it almost exclusively presents left-wing arguments to a left-wing public. Rather than standing apart from their audience, works like Shepard Fairey’s promotional designs for candidate Obama to Richard Serra’s visual denunciations of Abu Ghraib pander to existing assumptions and reaffirm the politics of their surroundings.

Audience resistance and censorship, by contrast, can sometimes illustrate the value of an artist’s political message. Such work may encourage the audience, however resistant, to see its politics in a new way. Sometimes this censorship is largely self-constructed, as in the case of David Wojnarowicz's “Fire in My Belly,” where a bad internal decision at the Smithsonian to remove the work from display was taken up by protesters as an opportunity to advance a political and monetary agenda. In that example, the work went from excluded to another form of propaganda, quickly landing in the permanent collection at MOMA. Other times the censorship is more serious, as now in China, where the state crackdown on Ai Weiwei speaks to the continued validity of his artistic project.

By these definitions, Mr. DeQuattro has the makings of a political artist, because as a conservative artist he currently stands outside of the politics of his own time and place. Regardless, student work deserves an especially generous standard for display. Mr. DeQuattro’s art should be supported by the same institution that invited him to hone his craft over the past five years. He should be afforded the same rights given to his classmates and allowed to exhibit in the group show. The fact that his politics are not shared by his peers does not render his art as irrelevant or “offensive.” Instead, it is a reason his political art is valid and deserves to be shown.