Thomas Hart Benton, Cut The Line (1944)

UPDATE: Welcome Painters' Table readers! Be sure to check out all of our art-related features.

THE AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE

April 2012

American Scenes

by James Panero

A review of Thomas Hart Benton: A Life, by Justin Wolff; Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 432 Pages, $40.

Thomas Hart Benton was a painter who could appear on the cover of Time magazine one year only to be drummed out of the New York art world the next. He was a child of privilege--the son of a U.S. Congressman and the great nephew of a famous senator--who developed his own progressive artistic style to elevate provincial Americans over East Coast elites. A mentor and friend to Jackson Pollock, he nevertheless railed against the rise of Abstract Expressionism and served as a whipping boy for the avant garde.

He was a “man who could be so charming and so crude, who was an anti-intellectual intellectual, and who scorned a career in politics but was profoundly political,” writes Justin Wolff in his new biography These contradictions make “Benton such a magnetic subject for the writer. We want to pin him down precisely because we cannot.”

For over half a century, art history has tried to wrestle Benton to the ground. He was “the favorite target of leftist critics and proponents of abstract art.” A goading antagonist, he often asked to be taken down. He went after the “coteries of high-brows, of critics, college art professors and museum boys.” After fleeing New York for Kansas City in 1935, he ranted that mid-Western artists

lisp the same tiresome, meaningless aesthetic jargon. In their society are to be found the same fairies, the same Marxist fellow travelers, the same ‘educated’ ladies purring linguistic affectations. The same damned bores that you find in the penthouses and studios of Greenwich Village hang onto the skirts of art in the Middle West.

“His poor judgment, profanity, and belligerent baiting of any artist walking a different stylistic or ideological path scandalized New Yorkers, New Englanders, and Missourians equally,” writes Wolff. “Over the years he opposed abstract art, curators, homosexuals, intellectuals, Harvard, New York City, Kansas City, women, and old friends like [Alfred] Stieglitz and [Lewis] Mumford, to name a few.” For a biographer who himself once dismissed Benton as a “conservative crank,” Wolff has now written a keen critical recuperation, if not a defibrillation, of this unique American artist.

“We were all in revolt against the unhappy effects which the Armory show of 1913 has had on American painting,” Benton once said of the seminal exhibition that first brought European modernism to New York. Benton represented the American reaction to this influence, an anti-avant-garde, but he came of age at the center of the vanguard of new art. He studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Academie Julien in Paris before settling into the progressive art circles of New York in the 1920s. Stanton MacDonald-Wright, the abstract painter, became a close friend. For fifteen years he experimented with cubism, pointillism, and synchromism--or rather “wallowed in every cockeyed ism that came along,” as he later admitted.

Thomas Hart Benton, Rhythmic Construction (1919)

Benton (the artist) once said that Senator Benton--his famous namesake, known as “Old Bullion,” who championed Western expansion--gave him “a kind of compulsion for greatness.” In 1924, he visited his home state of Missouri to attend to his ailing father, Maecenas, who had tried to persuade him to pursue law. Following the trip he determined to seek out his own American path in art. Benton soon got over his “French hangover,” according to the writer Tom Craven, and shed the “worn-out rags and fripperies of French culture” to “find himself as an American.”

A professor in art history at the University of Maine, Wolff is at his best exploring the philosophy behind the rise of Benton’s new signature style, which he locates in the pragmatism of John Dewey. Benton did more than merely react to the avant-garde. He developed a compelling counterpoint to modernism that he believed was far more populist and progressive than the art theories coming out of Europe. He came to see, writes Wolff, that art “should be instrumental (a favorite term of Dewey’s) and work to clarify ordinary experiences rather than interrogate the mysteries of the world. Based on such philosophies, Benton concluded that art should be realistic, not abstract, and that it should serve practical rather than intellectual ends.”

Thomas Hart Benton, People of Chilmark (1920)

The “distinctly American philosophy” of pragmatism, an anti-theory theory that related knowledge to “practical purposes,” meant that Benton was “more interested in common American experiences than in what many deemed the elitist aesthetic theories of avant-garde artists, who sought to justify experimentation and abstraction with a specialized, professional language. For many, then, Benton was one of them: he spoke their language, painted their lives, and believed wholeheartedly in the significance of their experiences.”

The critic Lewis Mumford gave Benton his regional focus, where “regional customs and spontaneous rituals, not our theories, account for the nation’s dynamism,” and “local customs and common experiences trump political or ideological categories,” writes Wolff. Mumford emphasized definitive, verifiable, and local knowledge. “The region provides a common background,” Mumford maintained, “the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat, the landscape we see, the accumulation of experience and custom peculiar to the setting, tend to unify the inhabitants.”

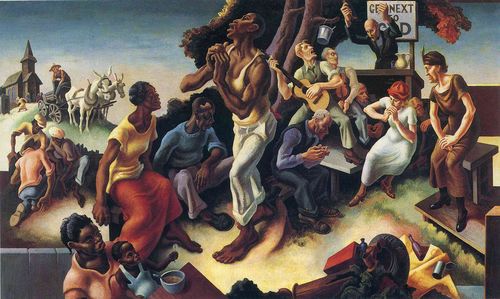

By the late 1920s, writes Wolff, Benton came to believe in “a devotion to experience, an anti-elitist concept of art.” He also saw that “centralized intellectual and political power was contrary to democracy.” The new art that he developed therefore sought to elevate people’s “regional” characteristics. He pursued a “Regional Survey” to reveal a population “with respect to soil, climate, vegetation, animal life, industry and historic tradition” (Mumford’s words). The format that Benton found most suited to this form of expression was the mural--large, populist, and capable of telling a multi-part story. He populated these expanses with colorfully molded characters drawn from studies made in small towns and urban ghettos across the country. He packed these fluid figures in energized, dense, and often cacophonous compositions in a style that became known as the “American Scene.”

Thomas Hart Benton, A Social History of the State of Missouri (1936) in the House Lounge in Missouri State Capitol. Jefferson City, Missouri

In his compositions, Benton was in part inspired by the realism of the nineteenth century French writer Hippolyte Taine. Folk songs also “appealed to Benton’s sense of narrative structure,” writes Wolff. “As in his murals, these songs present history anecdotally: in folk tunes, colorful characters and scenarios serve more general stories about injustice, labor, or outsider status.” He sought to restore republican virtues “through the rejuvenation of American folk traditions and values.”

Thomas Hart Benton painting Persephone (1938)

Benton shot to fame with his new style, appearing on the cover of Time magazine in December 1934, an unprecedented recognition for a living artist. In an article that profiled Benton and his fellow regional painters Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry, Time declared that Benton was “the most virile of U.S. painters of the U.S. Scene.”

By the early 1930s, Benton had successfully championed an art form that was equal parts populist and conservative. He received large mural commissions from the New School for Social Research (for a cycle called “America Today,” 1930-31) and the Whitney Museum of American Art (“The Arts of Life in America,” 1932). He also worked as a celebrated instructor at the Art Students League starting in 1926.

Yet a year after the Time article came out, Benton became embroiled in a controversy surrounding another famous muralist. It was an episode that would define his political trajectory as a “communist turned patriot,” writes Wolff, and also blacklist him in progressive art circles. Benton first met the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera while studying in Paris. Both artists used the same style to advance their own political positions. For Rivera, that meant Stalinism. In 1932, the Rockefeller family commissioned Rivera to paint a mural for the lobby of 30 Rockefeller Center, which the artist called “Man at the Crossroads.” For one figure in the finished cycle, Rivera swapped in the face of Vladimir Lenin. This forced Rockefeller to pull the commission and cover over the work.

The New York art world was in an uproar, but Benton remained ambivalent. A group of Left-leaning modernists seized on the opportunity to take him down. The artist Stuart Davis rallied the Arts Students League against him. In one altercation at the school, someone threw a chair at him. Benton “should have no trouble in selling his wares to any Fascist or semi-fascist type of government,” declared Davis. “[His] qualification would be, in general, his social cynicism, which always allows him to depict social events without regard to their meaning.”

Writing in Partisan Review a short time later, the historian Meyer Schapiro “excoriated Benton’s apparent nationalism and ‘strong masculine’ figures, which he felt were dangerously similar to the xenophobia and idealizing style of fascist art,” writes Wolff. In his populist murals, wrote Schapiro, Benton did not display the necessary Leftist political commitment, instead depicting “an escape from the demands of the crisis” that was “pitiful and inept.”

After the Rivera episode, Benton “never again pretended to stand on common ground with the radical Left,” writes Wolff. “Having a chair thrown at him by an angry communist, or being called a fascist, had as much to do with Benton’s reaction to radical leftism as did his pragmatism.” He left New York for the Midwest. The episode also demonstrated a flaw in realistic art that proved to be as equally fatal to Benton as Rivera: Politics of both the left and right could easily sully and co-opt realism. It was no coincide that didactic realism became the style of choice in both Fascist Europe and Communist Russia. Abstraction had no such political vulnerability. After backroom discussions between the Museum of Modern Art director Alfred Barr and Time’s Henry Luce, the same magazine empire that had crowned Benton king of the realists in 1934 championed the Abstract Expressionist Jackson Pollock in 1949 with a profile in Life magazine that asked, “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?”

The irony is that Pollock’s greatest influence was none other than Benton, his former teacher at the League. Benton started out an abstractionist only to become an infamous realist; Pollock went the other way, working through a regionalist style to arrive at his famous dripped abstractions. Much has been made with Pollock’s break with Benton. In 1944, Pollock declared Benton to be “something against which to react very strongly.” He once cursed Benton, exclaiming “God-damn you, I’m going to become more famous than you.” In the years following his drunken, fatal car crash in 1956, Pollock’s prophecy came true.

The critic Carter Ratcliff has argued that Benton’s influence on Pollock was a negative one. Benton was a surrogate for a “weak and absent father” says Ratcliff, and “didn’t want a son so much as a sidekick, a young and manipulable version of himself.” Pollock also “shamed himself” in aping after Benton’s style. But Wolff documents how Benton stayed close to Pollock until the end. “He answered Pollocks’ desperate late-night phone calls, refused to discourage his awkward infatuation with [Benton’s wife] Rita, and supported his career.” While dismissing his style, Benton also called Pollock “one of the few original painters to come up in the last ten years.”

Posterity has been far less charitable to Benton. As his style fell out of favor, several of his commissions from the 1930s were let go. The New School’s panels are now owned by AXA Equitable, which restored and now displays them in the lobby of its headquarters on Sixth Avenue in New York. The Whitney Museum sold of its panels in the 1950s to the New Britain Museum of American Art in Connecticut.

While I would have preferred a more chronological narrative and a more typical biographical structure, Wolff’s book makes a compelling case for making the pilgrimage to see them and giving Benton another look. “The panels of the America Today mural... floored me,” says Wolff. “the mural surpassed merely entertaining narrative. It possesses a palpable urgency.”

With our generation’s renewed interest in local culture and a skepticism of international progress, Benton’s philosophy seems ripe for reevaluation. “I believe I have wanted, more than anything else, to make pictures,” said Benton, “the imagery of which would carry unmistakably American meanings for Americans and for as many of them as possible.” While it may be arguable whether Benton achieved these ends, their pursuit now seems singularly compelling.

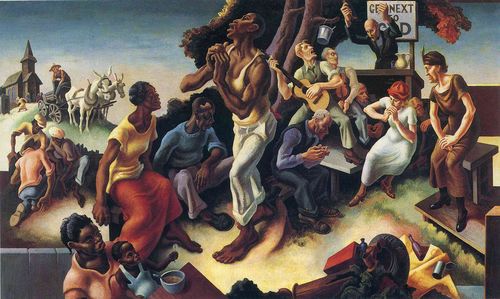

Thomas Hart Benton, The Arts of the South, from the mural The Arts of Life in America (1932) now in the New Britain Museum of American Art